The case of David Miranda got a lot of attention around the world after UK authorities were accused of abusing an anti-terrorism law to evade the normal constitutional restrains on police power and question someone because of their political associations. Well, a very similar abuse of power appears to have happened here in the United States.

Today we are releasing new government documents that provide rare insight into how the government uses its powers at the border to search and seize Americans’ electronic devices. The documents, obtained by our client David House as a result of his lawsuit against the Department of Homeland Security, demonstrate how the government is abusing its border search authority to evade constitutional restrictions on its surveillance powers. (You can see the documents here.)

House was stopped at Chicago’s O'Hare International Airport coming back from vacation in November 2010. At the time, he was working with the Bradley Manning Support Network, which was raising funds for the legal defense of the soldier who has since plead guilty to providing classified documents to WikiLeaks. DHS agents detained House, interrogated him about his political activities and beliefs, and then seized his laptop computer, mobile phone, camera, and USB drive. The agents returned House’s phone after inspecting it, but the government kept the rest of his devices for seven weeks while agents searched his files for evidence. Even after the government returned House’s physical devices, it continued to actively investigate copies of his files for nearly six more months.

The ACLU and the ACLU of Massachusetts filed a federal lawsuit on House’s behalf arguing that the government targeted House solely because of his association with the Bradley Manning Support Network, violating both his First Amendment right to freedom of association and his Fourth Amendment right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures.

In March 2012, the judge in the case denied the government’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit, holding that even though the government does not need suspicion or a warrant to search people’s electronic devices at the border, that power is not unlimited and First Amendment rights still apply. After months of negotiations, House and the government inked a settlement agreement in May 2013. As part of that agreement, the government agreed to destroy all of the data it got from House’s electronics, and also turn over documents related to its investigation of House and the search of his devices.

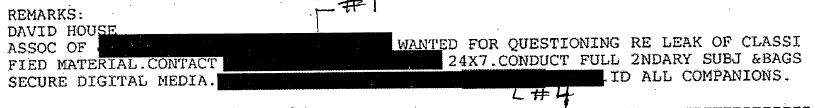

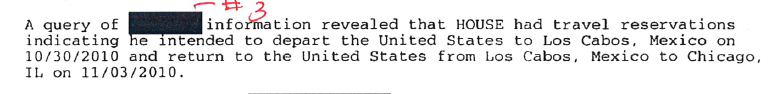

The settlement documents reveal that an agent with Homeland Security Investigations (HSI)—an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) subdivision that is now the second largest law enforcement agency in the United States—entered a “lookout” into a government database called TECS (see the document here), effectively notifying government agents throughout the country that House was wanted for questioning in connection with the Department of Justice’s investigation into Manning and WikiLeaks. As a result of the lookout, which was linked to the Advance Passenger Information System, HSI later received an automated notification that House would be traveling outside the country and that he would return through O’Hare on November 3, 2010.

House’s case provides a perfect example of how the government uses its border search authority to skirt the protections afforded by the Fourth Amendment. The government enjoys wider latitude to search people and their belongings at the border than it possesses elsewhere, for the purpose of protecting our borders. But the settlement documents demonstrate that the seizure of House’s computer was unrelated to border security or customs enforcement. It was simply an opportunity to conduct a suspicionless search that no court would ever have approved inside the country.

The records also show that HSI was acting in cooperation with—and perhaps at the request of—the Department of Justice, the Department of State, and the Army’s Criminal Investigative Division, not to protect our borders but to further a domestic investigation of the WikiLeaks disclosures. House’s connection to Manning through the Bradley Manning Support Network made him a target of that investigation. The government then used its access to airline passenger information to learn when and where David House, and others, would be traveling across our border (see the document here), and laid in wait to seize his computer and other electronic devices.

Electronic device searches are substantially more invasive than traditional border searches, which is why this particularly intrusive form of government surveillance should not be conducted without reasonable suspicion. The documents show how, using sophisticated forensics software, the government can conduct comprehensive and intrusive searches of the large number of personal documents stored on today’s electronic devices. In this case, the government searched House’s electronics for 183 keywords, turning up more than 26,000 potentially responsive “files/objects”. But even the government’s own analysis of House’s information concluded that “no data was found that constituted evidence of a crime (and would justify ICE’s seizure of the materials).”

The fact that an American crosses the border should not be an excuse for the government to scour his most personal files or to seize his electronics for a prolonged period of time. A federal appeals court recently said that the forensic examination of a person’s laptop is so “comprehensive and intrusive” that the government should not be allowed to search such devices at the border without reasonable suspicion of wrongdoing.

The documents expose the government’s process for searching electronic devices at the border—and it is not reassuring. Although the government reports searching thousands of electronic devices a year at the border, the details of how it conducts these searches have been largely kept secret so far. ICE’s policy states that electronic device searches should generally be completed within 30 days, but it took some seven months for the government to complete its search of House’s information and conclude that there was no evidence of wrongdoing data. During that period, House’s devices were imaged multiple times and shared with another government agency, the Army Criminal Investigation Division.

Unfortunately, House’s case is not an isolated incident. The government’s own records indicate that 4,957 passengers had their electronic devices searched between October 1, 2012 and August 31, 2013, and an additional 4,898 individuals were subject to electronic device searches the previous year.

We have no way of knowing how many of those searches may have been carried out not to search for contraband—which is the reason ICE has been granted such broad search powers—but to exploit border search powers to evade the Constitution.