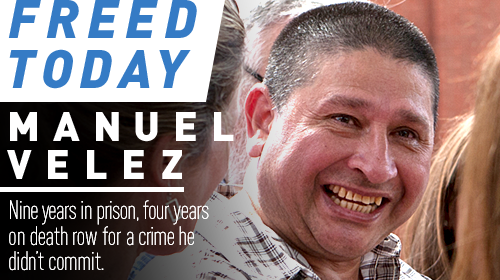

At 12:32 p.m. ET, Manuel Velez, my client and an innocent man, stepped out of prison and into the Huntsville, Texas air a free man.

For nine years, Manuel has languished behind bars. What's ironic about watching him walk out of this particular prison, the Walls Unit, which is often used to process releases, is that is better known for its executions. The state of Texas has executed more than 500 men and women here. Manuel was almost one of them.

Manuel was condemned to death in a 2008 trial for the 2005 killing of Angel Moreno, his then-girlfriend's one year-old son. Angel died of brain trauma. The state's medical experts presented the case as a simple one – his head must have been slammed against the wall or some hard object. But they failed to recognize a medical report in their own file that showed Manuel was innocent.

The report showed indisputably that Angel's head injuries occurred at a time when Manuel was a 1000 miles away, working construction in Tennessee. The neuropathologist the state used to examine Angel's brain under a microscope had made findings on the timing of the child's head injuries and put them in the report, which the state's testifying experts completely ignored. Manuel's court-appointed counsel also missed these crucial facts, along with other medical evidence, proving this timeline. Manuel was too poor to hire his own attorney.

On appeal, the courts held the attorneys' failures to be constitutionally inadequate, and they ordered Manuel be given a fair, new trial. But there were other problems too.

Manuel, a native Spanish speaker and seventh-grade dropout, is functionally illiterate in both Spanish and English. The police had on hand a video recorder to record interrogations, and in fact used it for his codefendant, Angel's mother. But they did not record Manuel's interrogation.

Instead, they typed up two different statements in English and had Manuel sign them without being able to read them. The statements were full of false claims, including that Manuel shook, bruised, and bit the baby – things that absolutely never happened. Because prosecutors liked one of the statements better – it had more of these false facts – they presented it to the jury as the only true statement, and claimed the less guilty one was a defense fabrication. But it was the prosecutors who were fabricating.

The deceit, however, didn't end there. They committed further misconduct by not correcting the codefendant mother's bogus claims to the jury about the nature of her plea agreement in which she falsely minimized her own responsibility. And that's not all. The Texas Court of Criminal appeals reversed the death sentence from the 2008 trial because the prosecutors presented testimony about prison conditions they knew or should have known was false.

In spite of all this, it was only a fluke that Manuel's innocence was discovered. A Texas law professor was concerned that Manuel could be intellectually disabled and so asked my office and two outstanding law firms – Carrington, Coleman, Sloman & Blumenthal and Lewis, Roca Rothgerber – to work on Manuel's appeals. It took armies of lawyers to prove Manuel's innocence, but far too many men strapped down in the execution chamber yards away have never had a single good lawyer working on their case. Under our broken system, innocent people have been and are going to continue to be executed until the death penalty is abolished.

If it's possible to add one more bit of injustice to Manuel's story, there's this. To guarantee his freedom and seeing his family today, he has pleaded no contest to recklessly injuring Angel – by failing to report his mother's abuse. We would have preferred to take Manuel's case to trial to prove his innocence and hear the words "not guilty," but we couldn't justify the risk of failure, or further injustice at the retrial. We couldn't take that risk with a plea to time served on the table. So while he comes home free, he's still tainted by this broken system.

But right now is a time for happiness. For the next six-and-a-half hours, Manuel, I, and his other lawyers will be in a van making the 420-mile trip to his sister's home in Brownsville, just across the river from Mexico. There his family is waiting to greet him, a man they knew could never do what he was accused of and sentenced to die for.

Since Manuel was locked away, his mother and father have become elderly and frail and have learned to survive without his support. His sons Ismael and Jose Manuel have grown from a toddler and first-grader to teenagers. Elmita, Leticia, Marisol, Virginia, Rafael, and Wenceslao, his siblings, have learned to compensate for their missing brother. Nieces and nephews have gone without the ice cream and barbecue Manuel loved to share.

Until now.

After 420 miles and nine years, this is going to be one joyous reunion.

Learn more about the death penalty and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.