In a Case that Rocked Alabama, a Man With Intellectual Disability Is Spared Death

This week, in one of the highest profile cases in Alabama history, longtime ACLU client Lam Luong was resentenced to life in imprisonment without parole, nine years after he was sentenced to death. Luong’s life was spared because experts hired by both the state of Alabama and the defense agreed that he met the criteria for intellectual disability.

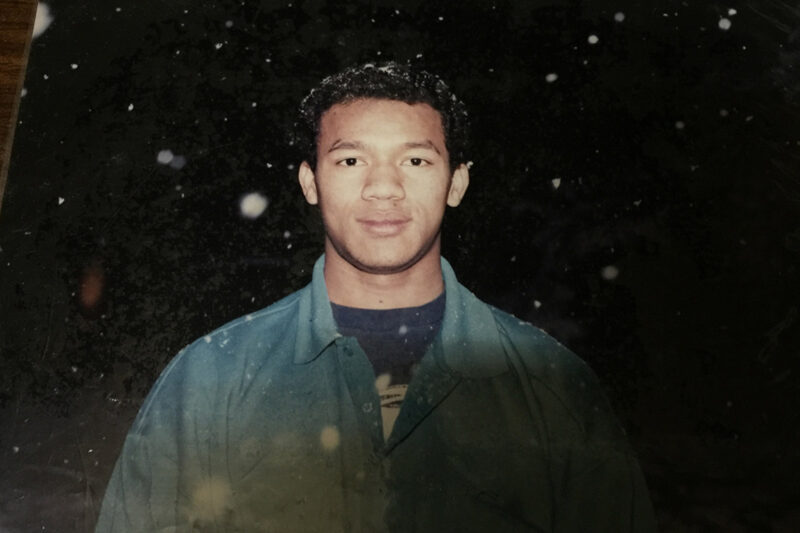

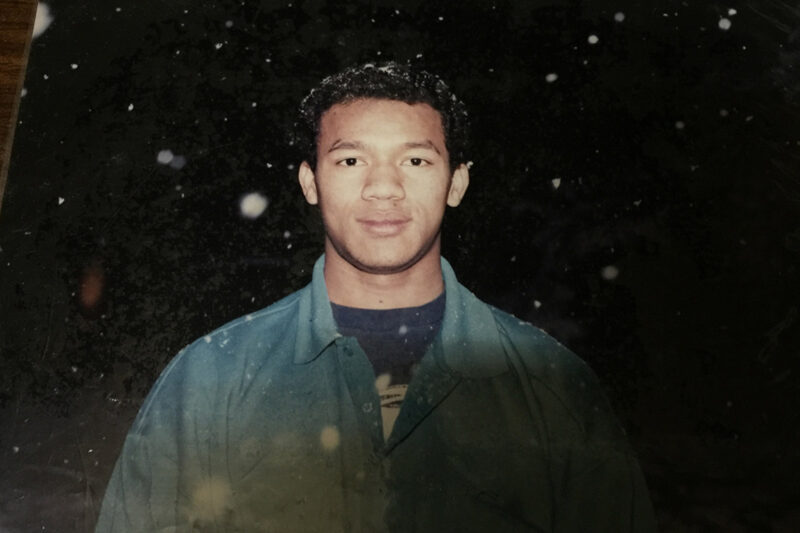

Luong, born during the Vietnam War to a Vietnamese woman and a Black American serviceman, was convicted and sentenced to death in the spring of 2009 for the murder of his four young children on the Dauphin Island Bridge in Alabama.

In 2002, the Supreme Court held in Atkins v. Virginia that the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution prohibits the execution of persons with intellectual disabilities. There was no question that Luong met the criteria. Almost a decade after his original conviction and death sentence, the state finally agreed that Luong could not be executed and joined the defense in asking to change his sentence.

After Luong received a life sentence this week, Mobile County District Attorney Ashley Rich complained that no one who encountered Mr. Luong in 2008 and 2009 noticed any signs of intellectual disability, including the “very experienced members of the bar specializing in criminal law” who represented him at trial. Lawyers, of course, aren’t mental health professionals by trade. And while it’s true that Luong’s trial lawyers did not hire a psychologist to investigate the question, Rich’s complaint speaks volumes of the due process mistakes that plagued the case from the beginning and nearly cost Luong his life.

How did Luong get sentenced to death long after the Supreme Court ruled on the issue? Judge Charles Graddick — who during his 1978 campaign to become Alabama’s attorney general committed to “fr[ying] [murderers] till their eyes pop out and smoke comes out of their ears” — presided over the 2009 trial. Responding to intense community pressure, Judge Graddick was determined to fast-track Luong’s case, and he was convicted and sentenced to death in a record 14 months after the crime. Most Mobile County capital cases aren’t even indicted in that period of time, let alone tried.

In the rush to try Mr. Luong, Judge Graddick took shortcuts and ignored Luong’s constitutional rights, letting the passions of the community guide a complex death penalty case involving a multi-cultural defendant who spoke little English. As a result, Luong’s lawyers and Judge Graddick alike missed the obvious signs of Luong’s intellectual disability and severe mental illness.

Even the state’s psychologist — the only psychologist hired by any party to evaluate Luong — conducted such a cursory evaluation that he did not bother to administer any intelligence tests to the defendant. Judge Graddick refused to give the trial lawyers any funds to investigate Luong’s life history in Vietnam, where he spent his childhood, suggesting instead that they attempt to interview family members by video conference.

The ACLU first took Luong’s case on appeal, challenging, among other things, some of Judge Graddick’s shortcuts. In a remarkable decision given the politics of the case, the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals in 2013 unanimously ordered a new trial. The court found Judge Graddick erred in refusing to change the venue of the trial to a location outside of Mobile, despite a flood a prejudicial, pretrial publicity. The decision also found the judge erred in refusing to allow Luong’s lawyers to question potential jurors individually about their exposure to the publicity and in denying funds to conduct the Vietnam investigation.

At that point, the state of Alabama could have conceded error and allowed Luong a new trial to remedy these constitutional violations. Instead, the state, led by then-Attorney General Luther Strange and supported by Mobile District Attorney Ashley Rich, decided to appeal the court’s decision to the Alabama Supreme Court. In 2014, a divided court, led by then-Chief Justice Roy Moore, reversed the lower court’s decision on every claim.

In the next stage of his appeals, the ACLU conducted the life history investigation that Judge Graddick had denied Luong's trial lawyers. We uncovered extensive mitigating evidence that had never been found, including information making Luong’s intellectual disability plain.

To meet the criteria for intellectual disability and qualify for the exemption to the death penalty under state and federal law, a person must have significantly subaverage intellectual functioning, subaverage adaptive functioning, and onset of the disability in the developmental period. Experts hired by Luong and the state of Alabama in the post-conviction stage agreed that Luong met the criteria and was therefore ineligible for execution. Luong received IQ scores of 51, 49, and 57 on four different IQ tests administered by state and defense experts. He received scores of 61, 55, and 60 on adaptive functioning instruments. The experts agreed that Luong’s disability manifested prior to the age of 18.

Other people with intellectual disability continue to be sentenced to death and executed in this country. Thankfully, the Alabama Attorney General’s Office followed the letter of the law and reached the right result here.