Billy Wayne Coble was convicted of a Texas triple homicide in 1989. On Thursday, he is scheduled for execution.

A former ACLU client, Coble’s story was not a happy one before he found himself on death row. He was a Vietnam veteran who had been raised by a mother who was institutionalized for mental illness and by a father debilitated by alcoholism. But if Coble’s execution goes forward, he will be killed not for who he is or for what he’s been convicted of, but because of the testimonies of so-called “experts” whose testimony can be summed up in two words: unreliable junk.

Years after Coble was initially sentenced to death in 1990, an appellate court in 2007 threw out that death sentence because the trial judge had erred in instructing the sentencing jury. At Coble’s 2008 re-sentencing trial, his behavior in prison between 1990 and 2007 posed a challenge to the state’s claim that, as required for a Texas death sentence, Coble would be a danger to other prison staff and prisoners if not executed.

As the court later described him, Coble “did not have a single disciplinary report for the eighteen years he had been on death row.” Rather than posing a threat, Coble had instead become known for helping both staff and fellow prisoners alike.

To meet Texas’s future-danger requirement, which would require checking and countering his years of good behavior, the state’s first move was to present testimony from Dr. Richard Coons, a psychiatrist who, over the years, had claimed Texas prisoners would be dangerous to those around them if not executed. It was no surprise that he did the same in Coble’s case.

But, when scrutinized, it’s clear that Coons’ predictions more closely resembled backroom fortune telling than science.

As Coons has now admitted, his testimony, in both Coble’s and previous capital trials, was not based on any peer-reviewed literature, field of study, or empirical research. Rather he himself admits, as the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals noted in 2010, to doing “‘it his way’ with his own methodology and has never gone back to see whether his prior predictions of future dangerousness have, in fact, been accurate.” Coons was a fraud, plying his trade to help Texas prosecutors secure death sentences.

Texas’s second move to secure Coble’s death sentence was to present A.P. Merillat, a prison investigator, as yet another bona fide “expert.”

For Texas prosecutors, Merillat played a similar role to that of Coons: to give juries a reason to believe a prisoner must be executed to prevent future danger to those around him. Merillat did so for years by enthralling juries with horror stories of prison violence. He also swayed juries by pointing out supposed loopholes that he claimed provided prisoners opportunities to commit violence if sentenced to life imprisonment instead of death.

But Merillat has also been proven a fraud.

In a pair of separate appeals we litigated on behalf of our clients Adrian Estrada in 2010 and Manuel Velez in 2012, Texas’s highest court found Merillat’s claims in each case demonstrably false. Merillat falsely conjured relaxed security restraints our clients would have enjoyed if not sentenced to death, restraints that would make letting them live more dangerous.

When Coble’s death sentence was appealed in 2010, Texas’s highest court agreed that Coon’s predictions were unscientific and never should have been presented to the jury.

But, in a curious twist, the court cited a technicality to uphold Coble’s death sentence. It found that the erroneously admitted testimony was harmless. It was then that we entered the case, assisting Coble and his attorneys by arguing for the U.S. Supreme Court to take his case. Regrettably, we were unsuccessful.

Coble has since continued to fight in lower courts to overturn his death sentence, which still stands despite the fact that the state of Texas has long since given up defending the merits of Coons or Merillat. A federal appellate court recently called them, “two problematic witnesses.” It observed, of Coble’s trial, “that Coons’ testimony was unreliable and should have been excluded” and that “the State does not dispute that parts of Merillat’s testimony were fabricated.”

Yet the federal court allowed Coble’s death sentence to stand, again based on technicalities. It agreed with the theory that Coons’ testimony was harmless, and it cited technical failures by Coble’s lawyers to raise challenges to Merillat’s testimony using the correct, if byzantine, procedures.

Since the court findings repudiating them in 2010 and 2012, neither Coons nor Merillat has appeared as experts for Texas prosecutors. Simultaneously the number of new death sentences in Texas has continued to plummet. Yet Coble’s execution remains stubbornly and glaringly on track over technicalities, despite the admittedly “problematic” testimony used to make the state’s case for death.

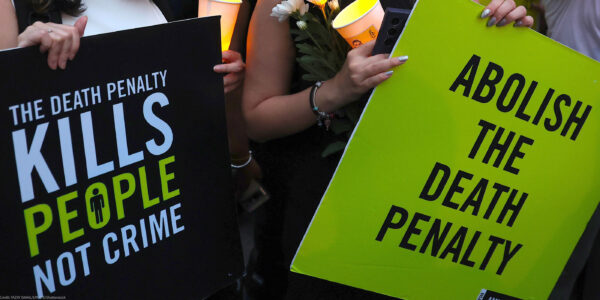

That Coble will be executed on such discredited testimony is unconscionable. The courts’ recognition that Coons was trafficking in junk science and Merillat in fabrications may have come too late to save Coble’s life. But the example of his case already shows all who are willing to look why the death penalty is never justice, and why it should be abolished once and for all.