Major Hack of Camera Company Offers Four Key Lessons on Surveillance

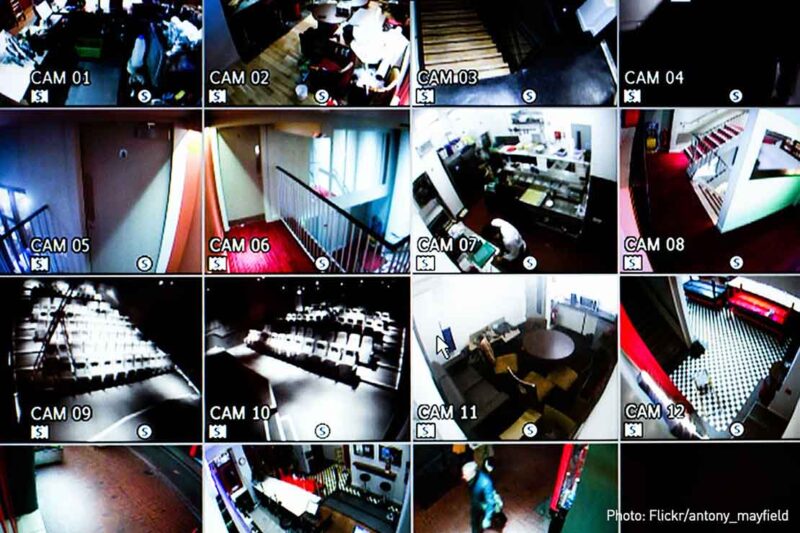

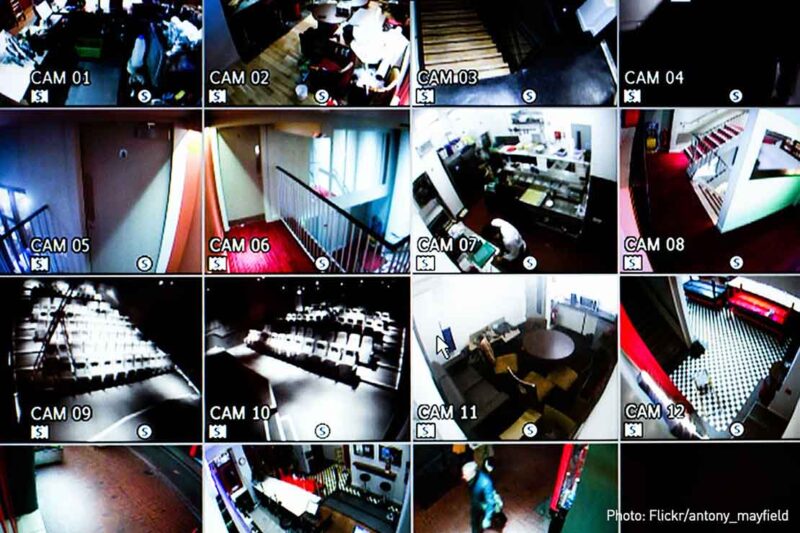

We learned last week that a group of hackers gained access to cameras installed by a surveillance camera company, and said they were able to access live feeds from 150,000 cameras inside schools, hospitals, gyms, police stations, prisons, offices, and women’s health clinics. Some of the video footage — showing patients in their hospital rooms, for example — was extremely privacy-violating.

The company, Verkada, does not merely sell security cameras; it also provides a variety of surveillance services to its clients, including cloud storage of video footage and remote access to camera feeds on smartphones or other devices. Because the company streams video to a centralized source (its servers) to provide these services, the hackers were able to access not just a few cameras here and there, but a vast number of video feeds.

What does this breach tell us about the state of security today? While the story has many dimensions, it offers four principal reminders about surveillance, video, and internet-connected devices.

1. The dangers of connected cameras

When you hook up a camera to the internet, you are making it vulnerable. And you are making the privacy of anybody recorded by that camera vulnerable. We have previously warned people who are considering buying a doorbell camera or other internet-connected camera for their home — or other kinds of “Internet of Things” devices — that they are susceptible to hackers. In this case, the hackers reported that they were able to watch video showing such things as a man struggling with staffers inside a psychiatric hospital, a man being interrogated in a police station, patients in a hospital intensive care unit, and a family doing a puzzle inside their home. The hackers reported accessing not just live video but also videos customers had saved to the cloud — in other words, onto Verkada’s servers.

Digital security is difficult. The bottom line is that it’s simply easier to attack an online asset than to defend it. To protect it, your defenses have to be perfect, while an attacker only needs to find one way to succeed — one weak password, one unpatched vulnerability, or one gullible worker. Many companies, especially less established ones, don’t make cybersecurity a priority. That’s because good cybersecurity is expensive, and with the occasional exception of a few days’ bad headlines, the consequences of failure typically fall on others, rather than on the company.

2. Device vendors can be device snoopers

Internet-connected devices are vulnerable to three broad categories of privacy invasion: hackers, the government, and the companies that make the devices. We don’t know of any government intrusion here — though any collection of sensitive data is vulnerable to domestic or foreign governments through legal or other processes. But this breach is certainly a reminder of that third vulnerability.

The intruders gained access through a pre-existing Verkada “Super Admin” account that let employees watch video from any of the company’s cameras. The very existence of such an account is a scandal in itself. Bloomberg and IPVM reported that the use of these Super Admin accounts was widespread within Verkada, with more than 100 employees having access. One former executive told Bloomberg that such access extended to sales staff and “20-year-old interns.” It’s unclear how many (if any) of Verkada’s customers knew about this centralized access, though if any did, they weren’t notified when it was happening — and it’s pretty likely they didn’t expect it to be so casually used.

Unfortunately, such centralized access to surveillance feeds by vendors is hardly surprising. Ring, the Amazon-owned doorbell camera company, gave workers access to every Ring camera in the world together with customer details. Other companies offering similar services have also granted such access, including Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Facebook.

3. The inappropriate deployment of cameras

By providing a window into video surveillance systems across a wide range of institutions, the Verkada hack reveals how some of those institutions deploy cameras in inappropriate or unethical ways.

If I were lying in an ICU bed, I know I wouldn’t want a camera on me. And if there was a camera set up for observation by medical staff, I certainly wouldn’t want it sending data to the internet. Nor would I want an internet camera on me while I worked out at a gym or visited a clinic, or on my children at school. If there was a camera, I’d like to know it — and if it were connected to the internet or using face recognition I’d like to know that, too.

Videos viewed by Bloomberg showed that in one Alabama jail, cameras were hidden inside vents, thermostats, and defibrillators, and tracked both incarcerated individuals and correctional staff using face recognition. If that jail could do that, so presumably could any of the company’s clients who chose to do so.

Aside from Verkada’s failings, these institutions have failed the people who appeared on their cameras. Most of the subjects of this surveillance were not Verkada’s customers, had no relationship with Verkada, and probably were not even aware of the company’s existence. Even if Verkada had the best, most transparent contractual relationship with its customers, many of those subjects were still being surveilled in ways they shouldn’t have been.

4. The power of face recognition and video analytics

Among the services that Verkada offers are face recognition and other video analytics, including “people and car detection” as well as intelligent search functions that allow for “search and filter based on many different attributes, including gender traits, clothing color, and even a person’s face.”

We have written in detail about how video analytics can let computers not just store video but understand, analyze, and intelligently search it. That is making video a more powerful and intrusive surveillance mechanism. But it could also make video a more valuable asset for hackers. If face recognition or other characteristics are pre-computed, for example, the video archive could become more manageable to an attacker looking for a specific target.

In that respect, one finding was troubling: According to images viewed by Bloomberg, cameras in the offices of the company Cloudflare were using face recognition, but the company said that it has “never actively used it.” If the company is telling the truth, that would suggest that face recognition was being applied to a customer’s video by Verkada without that customer’s knowledge.

These four lessons should be taken to heart by policymakers, institutions, and individuals. The Verkada hack involved a veritable Russian nesting doll of victims: The hackers breached Verkada, which appears to have been intruding upon its customers by allowing free access to their video feeds. And those customers betrayed those who appeared on Verkada’s cameras not only by putting too much trust in the company in particular and in cloud services in general, but in many cases by collecting video that was inappropriate in the first place. Verkada touts centralized management of video as a must-have security feature, but this hack dramatizes the downsides of such centralization. Instead of providing security to its customers and the people captured by their cameras, that centralization provided invasion and insecurity.