For Black Men, Running Is a Reasonable Reaction to Police Harassment and Racial Profiling, Concludes Massachusetts’ Supreme Court

In 2004, University of Virginia football player Marquis Weeks returned a kickoff 100 yards for a touchdown. After the game he described how he did it: "That was just instinct," Weeks said with a laugh. "Kind of like running from the cops, I guess you could say."

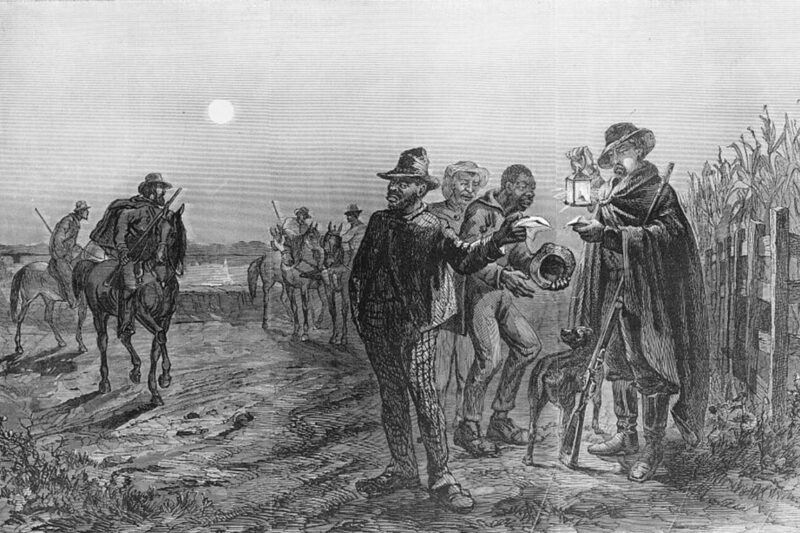

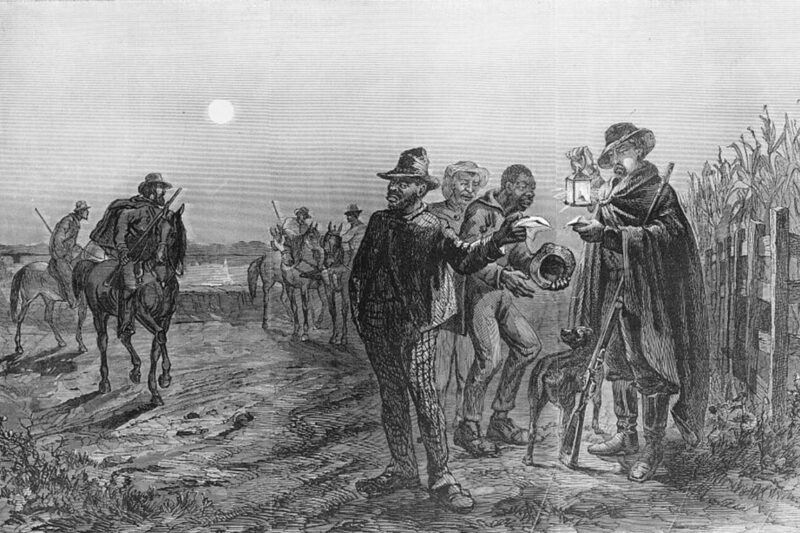

It’s funny until it isn’t. The “instinct” exists for a reason. Black and brown people have been running from people with badges for generations, going all the way back to the days of the slave catchers, who were predecessors of modern-day police.

Despite his obvious speed, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court caught up with Mr. Weeks this month. The court found that the facts of the case, including that the young Black male suspect tried to avoid the police, did not justify a stop and search of the young man. The court, referring to an ACLU report on “Field Interrogation Observations (FIO)” used by the Boston Police, wrote:

“Rather, the finding that black males in Boston are disproportionately and repeatedly targeted for FIO encounters suggests a reason for flight totally unrelated to consciousness of guilt. Such an individual, when approached by the police, might just as easily be motivated by the desire to avoid the recurring indignity of being racially profiled as by the desire to hide criminal activity.”

Whether you call it FIO or stop and frisk does not matter because they are the same thing. In plain English, the court said that innocent Black people may be reasonable in thinking that the best thing to do when approached by police is to run. The facts about stop and frisk in Boston confirm what Black and brown people have known for years.

In between 2007-2010, people of color accounted for about 75 percent of those stopped by Boston police, 63 percent of them Black in a city where less than 25 percent of the population was Black. In more than 200,000 FOIs, Boston police seized weapons, drugs, or other contraband only 2.5 percent of the time. These disparities aren’t exclusive to Boston, far from it. The ACLU found similar records of police discrimination in New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Newark.

Reducing crime will never be accomplished by stopping and harassing innocent people in a racially disparate fashion, and those who suggest FIOs or stop and frisk as a crime solution are advocating policies that we know will fail — they have before and they will every time they are used. What will be accomplished if this practice continues unchecked is that innocent people of color will continue to learn that all too often the police are not there to serve and protect them. And sometimes the innocent may feel a strong instinct to run from the police to avoid the indignity and interference of being stopped for no justifiable reason.

The truth about our criminal justice system is harsh. To accept the truth about the criminal justice system will require us to challenge assumptions about the fairness of the system that we have comfortably made for decades. Our challenge is to deal with a system that has evolved to a point where racially based police harassment of innocent people is offered as a legitimate criminal justice solution. Race-based policing is a cancer on our justice system. And like any other disease, we must understand the true nature of the disease to cure it.

William Burroughs wrote his book “Naked Lunch” about the horrors of drug addiction. He said the title, suggested by Jack Kerouac, referred to “the frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork.” The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court had a “Naked Lunch” moment regarding the true nature of racially biased policing in Massachusetts: They did not like what they saw on the end of the fork, and neither should the rest of us.