Meet the Activists Fighting to Free People from LA Jails

Over the last year, the criminal legal system’s many injustices dominated mainstream discourse as people took to the streets to grieve and protest the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor by police, and COVID-19 took a devastating toll on people in jails and prisons. These events galvanized many people into action — in the streets, at statehouses, and online — inspiring them to join activists who have challenged the criminal legal system’s disproportionate and often tragic impact on communities of color.

One of the organizations at the forefront of this movement is the Youth Justice Coalition (YJC), a grassroots organization based in Los Angeles led by activists who have been incarcerated or otherwise entangled with the criminal legal system. The ACLU is part of a coalition representing YJC and impacted individuals in a lawsuit against LA County for its failure to adequately address the COVID-19 crisis in jails and prisons, and in protecting the health of incarcerated people.

We spoke with two YJC members, Nalya Rodriguez and Michael Saavedra, about how the past year has affected their work and how their personal experiences help to shape this movement for change. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

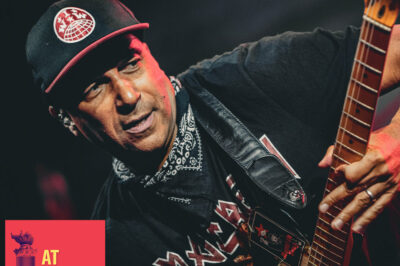

Justin Hamilton

How did you get involved with YJC?

MICHAEL: I spent close to 20 years in prison, and 15 of that was in solitary confinement. While I was incarcerated, I worked with a group of outside organizers on a hunger strike. It was one of the largest prisoner hunger strikes in this nation’s history. One of the things we asked for was access to higher education in solitary confinement. That’s how I was able to take some courses and later, enroll in community college.

I learned a lot about the legal system during my time locked up, including when I successfully sued the Department of Corrections several times over my solitary confinement, which violated my constitutional due process rights. Once I was out, I applied for a job as a paralegal and was hired on the spot. They discovered I was formerly incarcerated about six months later, and fired me. At that same time a position opened up at YJC and my roommate Anthony, who was also incarcerated, told me about it. I applied and got the job.

NALYA: I only recently got involved with the Youth Justice Coalition, but I was familiar with the work because I was a part of an organization in undergrad called Underground Scholars, which had an reentry program for formerly incarcerated and system-impacted students. During the pandemic, I’ve also been working with UCI 4 COLA and other partner organizations in North Orange County on an initiative to put together “solidarity packs'' for formerly incarcerated people. One of those partners was YJC, and that’s how I met Michael.

Justin Hamilton

Was there a turning point in your life that led you to organizing and activism?

NALYA: In high school, I was involved with gangs and didn’t really think I was going to college, even though I was already taking advanced classes. I hated school. I was always getting kicked out of class and spent a lot of time in the dean or principal’s office, and I was constantly told that I was either going to end up a teen parent or end up in jail or dead. It made school a negative experience. One day, literally the same day I was planning to drop out, a teacher intervened and asked, ‘Is this what you want to do with your life?’ That was the first time anybody had ever asked me that. I took a moment to pause and asked myself if I wanted to continue my life the way it is, or make a change. And I decided to make a change. I finished high school, got into Berkeley, and now I’m at UC Irvine studying for a PhD in sociology. Those experiences and seeing all of my friends go to court as teenagers, and just constantly being arrested and harassed by police officers — that’s what pushed me to get into this work.

MICHAEL: If you’ve been incarcerated for a long time, there are multiple turning points, starting with your public defender, who tries to get you to take a plea bargain even though you’re innocent. They don’t warn you that it will stay on your record for the rest of your life and harm you when it comes to housing and employment. That and many other experiences made me want to do the work that I do now, and also to become a lawyer and help people like myself to not have to rely on a classist and racist system.

Justin Hamilton

Can you describe a typical workday at YJC?

MICHAEL: As far as YJC, my day typically consists of taking calls as the lead on jail litigation. Since the recent announcement of the resentencing policy from [District Attorney] George Gascón, I've received a flood of calls and letters from folks inside and from family members out here asking for assistance with petitions for resentencing. I also work on letters from prisoners or calls regarding litigation. And prior to COVID, every other Saturday we would do free legal clinics to help people with immigration questions, expungement, tenants’ rights, debt relief, and things like that. Other than that, a lot of Zoom meetings with the many organizations we work with.

Justin Hamilton

How has the pandemic shaped YJC’s work over the past year?

MICHAEL: COVID has drastically changed things. It’s caused us to redirect our resources and take on all these calls from people in prison and their family members, who are sick or scared because of conditions inside. People have not been able to come into our legal clinics and not everybody can access support online. The community we serve in South Central is primarily Spanish-speaking and Black folks reentering society after being incarcerated and they don't know where to go. We had to shut down our office at the Justice Center, which has affected the ability to work for some of us who don't have computers or other office equipment at home. COVID has also changed the direction of our work. We usually work on policy impacting youth. Now we’ve been focusing more on incarceration, including women’s jails and prisons.

NALYA: For the legal correspondence program, we are creating self-help guides and informational sheets on rights in regards to the situation with COVID.

A memorial altar dedicated to people killed by the police or other state violence, and a mural depicting community peace-builders who were murdered or passed away before their time.

Justin Hamilton

What do you think people who aren’t impacted by incarceration misunderstand about the system?

NALYA: We need to make sure programs are accessible to non-English speakers. So I’ve worked with a lot of organizations that work with Central American newly-arrived immigrant youth. That’s one of the things that has continuously been an issue in LA and also in Oakland, where I’ve done similar work. There just hasn't been enough resources for Spanish-speakers or Indigenous people from Central America.

MICHAEL: One thing people fail to realize is that those same people called mafiosos or gang members, the worst of the worst, they're the ones that actually want to see peace. They have the respect of the community, and could tell the youngsters to kick back and they will respect that. And that's why we've been having this beautiful time of peace right now in South Central LA, which has been unheard of. YJC has led all of those peace treaty meetings taking place. We’re connected to the actual hood where all this stuff takes place, where people are overpoliced.

A lot of peacebuilding efforts have been unsuccessful because they are led by people who are not from the community and who have ties to the Los Angeles Police Department. Some of the biggest social justice organizations are run by people with white privilege, or white saviors. I don’t want to offend anybody, but it’s true. And they’re either working with the probation department, or they have contacts. They also have this thing called mandatory reporters. So whenever they go into a situation, they take down names and give this information to the LAPD, which puts it in its gang database. Now these people are labeled as gang members and that can be used against them if they ever get arrested, or in their housing.

I think we need to come together and educate folks and put formerly incarcerated people, people who are directly impacted, people of color in leadership positions, not just lawyers. And they need to be paid the same. We're called the experts and we're tokenized all the time to speak on the issue, but they don't want to pay us the same.

The Youth Justice Coalition works out of an office that is a converted juvenile court house.

Justin Hamilton

2020 was a difficult year, especially for many of the people you work with. But did anything good come out of it?

MICHAEL: For me, 2020 brought bright, beautiful things. I got accepted to UCLA and got a fellowship with Harvard Law School.

NALYA: I haven’t been with YJC for very long, but some of the work I’ve done in Orange County popped off in 2020, which is really awesome. We were able to raise money with collective community funds, which has been redistributed via solidarity packs for formerly incarcerated people. We also started a letter-writing program and mutual aid efforts, like food distribution — with that alone, we’ve raised over $35,000 and over $30,000 for solidarity packs, respectively.

These initiatives came from the need to address what we were seeing in our community in regards to COVID. People are in need of resources, and people are out of jobs. Our food distribution effort was a direct result of COVID, as well as the solidarity packs, which provide people who are just being released with personal hygiene kits, PPE, socks, snacks, gift cards, and other supplies they need.

Justin Hamilton

The Black Lives Matter movement has brought abolition to the forefront of the policing conversation. How does YJC approach abolition?

MICHAEL: Abolitionists say no more jails, no more cops. It’s an ideology about a utopia without prisons or police. But you have to have something to replace all of that. And that’s where we come in as members of the communities that are overpoliced. At YJC, we offer a real solution to no cops — we call it transformative justice and peacebuilding. So when you talk about taking cops off campus, we actually have a solution. We have a school without cops or even security. Instead, we have what we call peacebuilders who are trained on de-escalation and self-defense without any guns or weapons. We try to use our voices rather than violence.