The Use of 'Confidential Informants' Can Lead to Unnecessary and Excessive Police Violence

On Jan. 28, a group of heavily-armed men wearing Kevlar vests burst into the home of Dennis Tuttle and Rhogena Nicholas, a married couple in their late 50s living in the Pecan Park neighborhood of Houston.

Like many Texans, Tuttle and Nicholas kept guns in their home. One of the couple’s dogs ran at the men, who immediately opened fire and killed the dog. Tuttle, a Navy veteran, came from the rear of the house and began shooting at the armed intruders, wounding five of them. Nicholas grabbed at the shotgun being carried by one of the men. They responded by killing both Tuttle and Nicholas. But the men who gunned down this couple weren’t arrested afterward, because they were police officers executing a warrant to find drugs.

A judge signed the warrant authorizing this deadly raid because narcotics officers asserted that Tuttle and Nicholas were dealing heroin from their home. After police searched the bloodied home, though, all they found were personal-use amounts of marijuana and cocaine. There was no heroin, no piles of cash, no scales or other drug paraphernalia--nothing to suggest that the Tuttles were anything more than a couple who sometimes chose to get high in their own home.

Court documents released afterward showed that the raid was based on just two pieces of evidence: a phone call from Nicholas’s mother to police expressing concern that her daughter was doing drugs and a narcotics officer’s description of a “controlled buy” in which the confidential informant bought drugs from the Tuttles while he watched. Later, however, it became clear that the narcotics officer was lying: the drug buy had never happened, and there is no evidence the confidential informant even existed in the first place.

The fatal raid on Tuttle and Nicholas could not have happened but for three frequently-intersecting problems in policing: heavy reliance on confidential informants, inadequate mechanisms to identify when police officers or informants lie, and hyper-aggressive police raids using militarized tactics.

Bullet holes in Dennis Tuttle and Rhogena Nicholas' front door

Godofredo A. Vasquez / AP Images

The use of informants by police is essentially unregulated by the courts. In the 1960s, a trio of Supreme Court decisions — Hoffa v. United States, Lewis v. United States, and Osborn v. United States— made clear that police have a relatively free hand to use informants. The high court held that reliance on informant testimony implicates neither the Fourth Amendment’s protection from unreasonable searches and seizures nor the Fifth Amendment’s protection against self-incrimination.

As a result, law enforcement often exploit testimony from confidential informants, or CIs. However, the practice carries serious risks that the CI will give false testimony. CIs are often incentivized (via a promise of a plea deal or no arrest for their own accused offenses) to provide information that officers find useful, true or not.

If law enforcement provides these rewards without requiring corroboration from a noninformant source, then the CI has much to gain and little to lose from choosing to lie to satisfy the officer. When a CI has mental disabilities or a drug addiction, they can become even more vulnerable to manipulation by police officers seeking to use their testimony to make an arrest.

Even worse, when a CI program is allowed to operate without adequate controls, law enforcement can completely fabricate an informant’s existence. And the fact that this happened in Pecan Park shouldn’t be a surprise.

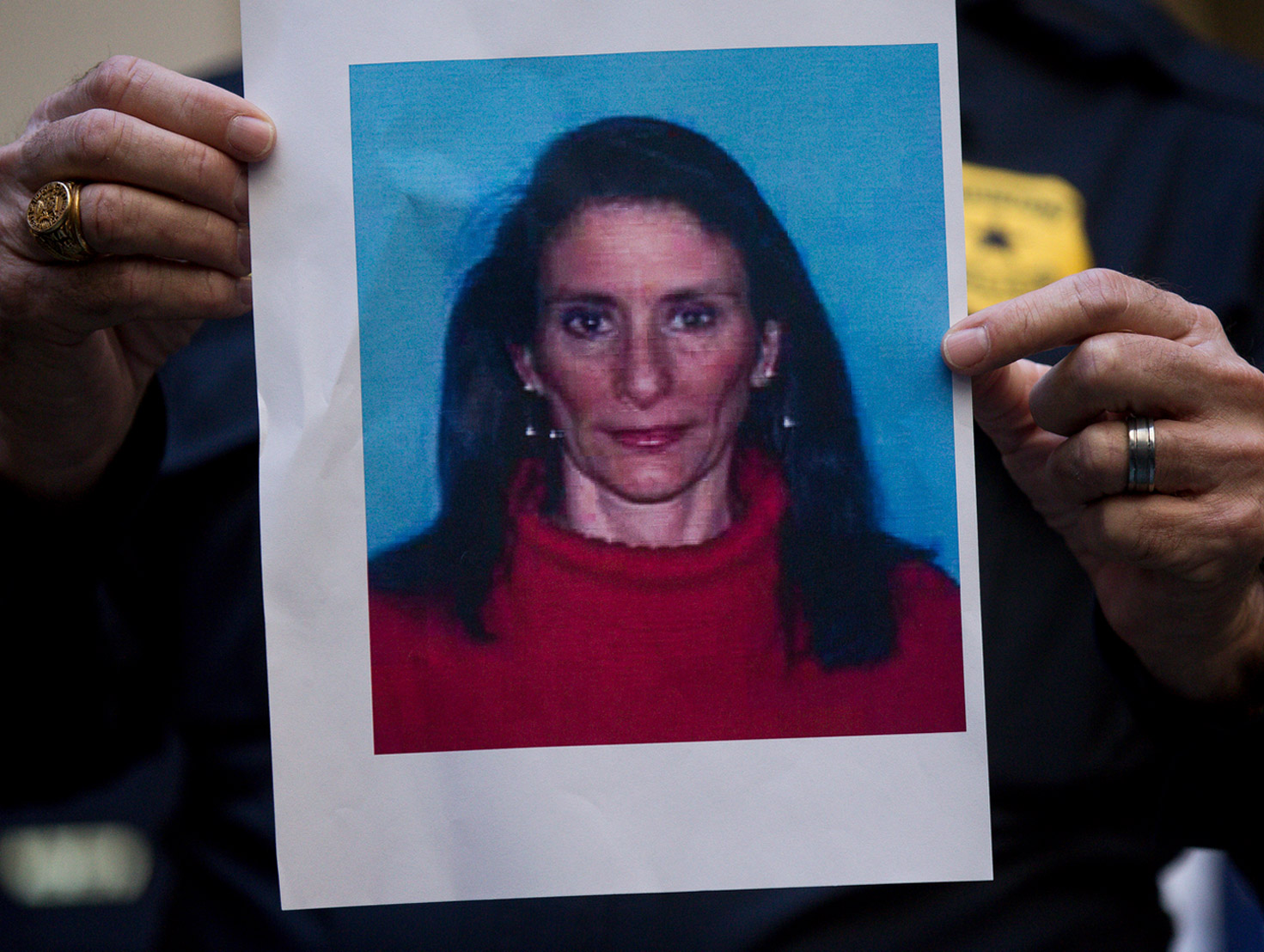

More than 12 years ago, in Atlanta, Georgia, a police SWAT team carried out a strikingly similar no-knock raid on Kathryn Johnston, a 92-year-old grandmother. The elderly woman fired a single shot at the home invaders — and they responded by killing her in a hailstorm of 39 bullets. Just like in this year’s Pecan Park raid, the police had obtained a warrant by asserting that a confidential informant bought drugs from Johnston’s house.

But both a federal and state investigation later concluded that the informant never existed. At the time, the ACLU proposed tighter controls on the use of informants to prevent similar tragedies, and Congress held a hearing on the misuse of police informants. But little national progress has been made since Johnston’s murder.

The tactics used by police in both Atlanta in 2006 and Pecan Park in 2019 make it even more likely that innocent people will be killed. Such raids are incredibly common.

According to a 2014 report by the ACLU, nearly 80 percent of SWAT raids were conducted to serve search warrants. Most of these warrants, 60 percent of them, were used to search for drugs, often as a part of low-level drug investigations. Moreover, no-knock warrants, in particular, were used in about 60 percent of incidents in which SWAT teams were searching for drugs, even though many of these searches resulted in law enforcement finding no drugs or only small quantities.

Police often justify these “no-knock” raids as a way to protect officer safety and prevent suspects from flushing drugs down the toilet before police enter. (Their name stems from their departure from standard police procedure, which is for police to knock and announce themselves as police to give the residents time to open the door before forcing their way inside.) But in reality, these tactics make tragedies almost inevitable for both officers and residents.

Take the 2014 cases of Marvin Guy and Henry Magee, two Texas residents who were both subjected to no-knock raids as a result of confidential informants providing bad information to the police. In both of these cases, CIs falsely claimed that Guy and Magee were selling large quantities of drugs, and police conducted no-knock raids in which each resident shot back at the intruders. The raids resulted in the deaths of two officers, and only negligible amounts of drugs were found.

When news of the botched Pecan Park raid first broke, the loudest voice was Joe Gamaldi, president of the Houston Police Officers’ Union. In a statement that oozed authoritarian contempt for the people he supposedly serves, Gamaldi condemned “the ones that are out there spreading the rhetoric that police officers are the enemy” and warned that “we’re going to be keeping track of all y'all," and "we're going to be holding you accountable every time you stir the pot on our police officers."

Around the country, police unions seem to believe their role is merely to offer reflexive opposition to even modest reforms and transparency as well as to demonize those who seek civilian control over police decision-making. In the weeks since then, however, higher-ups took a rare step by completely ignoring Gamaldi’s braying. Instead, they are moving to address the serious problems raised in this raid.

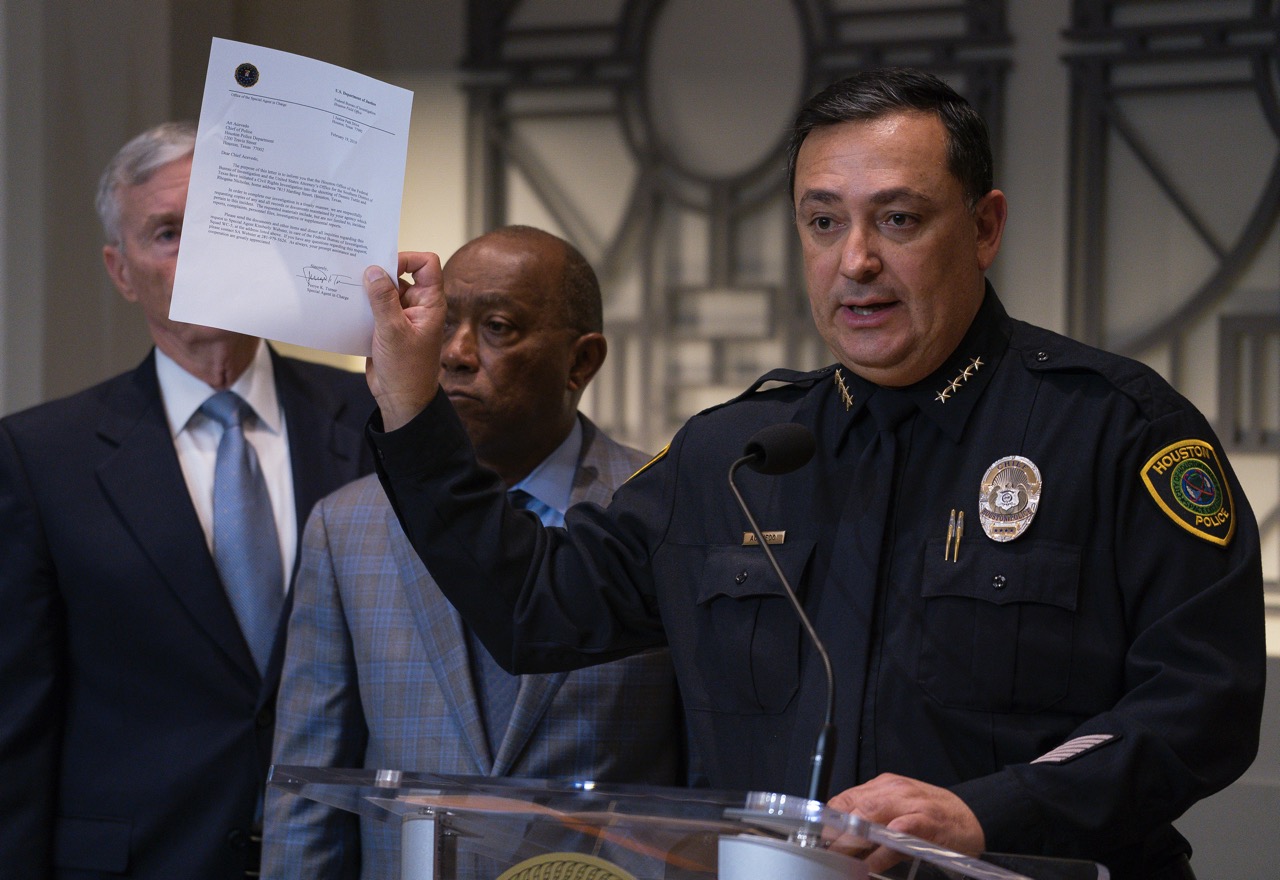

Houston Police Department Chief Art Acevedo holds up a letter from the FBI announcing the bureau's civil rights investigation related to the deaths of Dennis Tuttle and Rhogena Nicholas

Mark Mulligan / AP Images

On Feb. 15, Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo announced that he is going to largely end the use of no-knock raids. The Harris County Sheriff’s Office announced a similar policy change on Feb. 22. The ACLU hopes this will be followed not only by consequences for those officers responsible for the raid on the Tuttles, but also public transparency and a commitment to make any further policy changes needed to prevent similar tragedies in the future. Meanwhile, District Attorney Kim Ogg is reviewing the more than 1,400 cases Gerald Goines, the narcotics officer who fabricated the CI, worked on during his career.

Nothing can bring the Tuttles back to life. But if the Pecan Park raid leads to the kinds of controls that the ACLU has been demanding since Kathryn Johnston was killed in 2006, and that police union boss Gamaldi vocally opposes, that will at least be a clear sign of progress.

The Public Deserves to Know Whether They Can Trust Police Officers Who Testify in Court | ACLU

Another Day, Another 124 Violent SWAT Raids | ACLU

10-Hour SWAT Raid of Organic Farm? Just Another Day in the War on Drugs. | ACLU

Donate to the ACLU

The ACLU has been at the center of nearly every major civil liberties battle in the U.S. for more than 100 years. This vital work depends on the support of ACLU members in all 50 states and beyond.

We need you with us to keep fighting — donate today.

Contributions to the ACLU are not tax deductible.