Children Cruelly Handcuffed Win Big Settlement Against the Police in Kentucky

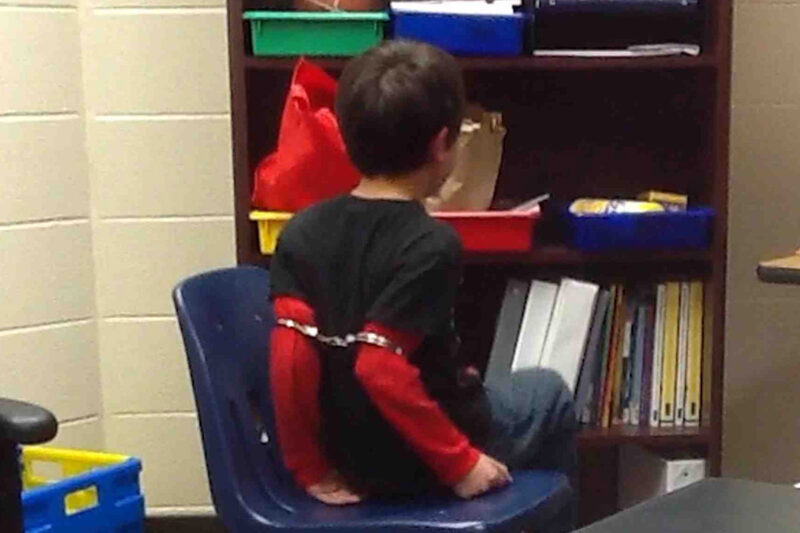

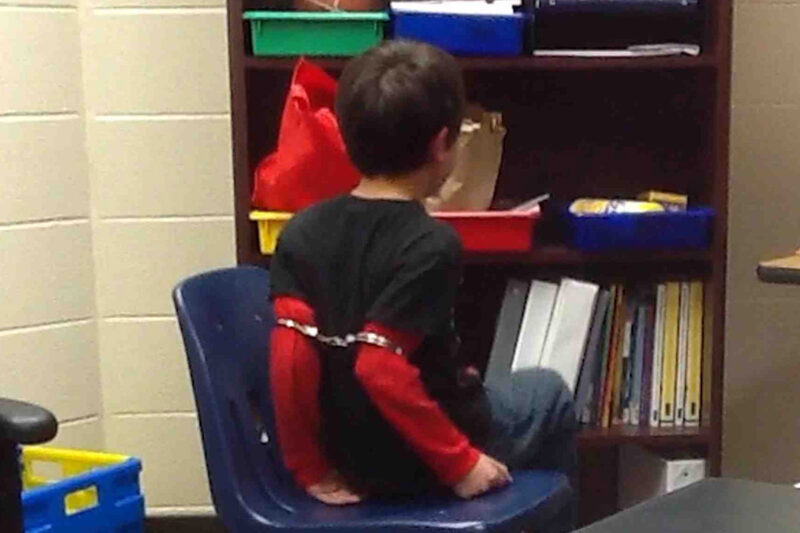

On Thursday, a sheriff’s office in Kentucky has agreed to pay more than $337,000 for the painful and unconstitutional handcuffing of elementary school students with disabilities. The two plaintiffs, both of whom were children of color and both of whom have disabilities, were so small that the deputy sheriff locked the handcuffs around the children’s biceps, forcing their hands behind their backs.

One of the cuffings was recorded in a video that went viral. The footage of the little boy, identified as “S.R.,” painfully squirming and sobbing in handcuffs drew national media attention and sparked debate over the role of law enforcement officers in schools.

Despite this video, and information that the deputy sheriff had handcuffed several other elementary school children — one as young as five — the Kenton County Sheriff’s Office insisted that the handcuffings were a proper use of force and refused to reconsider its policies. The ACLU, along with the Children’s Law Center and Dinsmore & Shohl, filed suit. In October 2017, a federal district court ruled that the punishment was “an unconstitutional seizure and excessive force.”

After the handcuffings, both children had repeated nightmares, started bed-wetting, and would not let their mothers out of their sight. Both families left the school district, and moved to areas where their children could receive the treatment and accommodations they needed.

The settlement comes as the national debate heats up over whether to boost the number of law enforcement officers in schools. The plaintiffs in this case were small children in need of support and understanding. They needed someone who understood the effects of their disability on their behavior and could help them with appropriate accommodations. Law enforcement does not have those tools. Indeed, the tools they do have — handcuffs, batons, pepper spray, and guns — are particularly inappropriate and harmful in the school environment.

There is no evidence that putting police officers in schools makes children any safer. What we do know is that 1.7 million children attend public schools that have cops but no counselors. Three million students attend schools with law enforcement officers, but no nurses. And six million students attend schools with law enforcement officers, but no school psychologists.

The brunt of these staffing choices falls most heavily and students with disabilities — especially students of color with disabilities. Students with disabilities are three times more likely than students without disabilities to be referred to law enforcement. Black girls with disabilities are 3.33 times more likely to be referred to law enforcement, and Black boys with disabilities are 4.58 times more likely to be referred to law enforcement.

The six-figure settlement is a small victory in the context of all the work that remains. But it highlights the harm of having law enforcement in schools — especially for young students with disabilities. We hope it will also open the door to more thoughtful discussions of how schools and our country can best support and educate our youth.