Cleaning Up the Snake Pit

The reform, and eventual closure, of the Willowbrook State School on Staten Island, New York, began with a phone call, oddly enough, from the Deep South.

In 1971, as executive director of the ACLU, I got a call from a prominent Alabama attorney, George Dean, asking for help. Dean told me he represented employees of the Alabama state mental health system. Alabama had ranked last among the 50 states in its per capita expenditure on the residents of its mental health institutions. Then-Gov. George Wallace had cut the system’s budget, forcing layoffs. Employees who had lost their jobs had retained Dean to represent them. In doing so, Dean argued that the layoffs denied residents of those institutions a right to treatment.

The case came before an iconic federal judge in Alabama, Frank Johnson, who had been appointed by President Dwight Eisenhower and was renowned for his concern for civil rights. Among other historic decisions, Judge Johnson had decided in favor of Rosa Parks’ right to sit wherever she pleased on the buses of Montgomery, Alabama. Some years later, he had held that the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. and other activists had a right to march from Selma to Montgomery. Gov. Wallace hated Judge Johnson. At one point, after Johnson had ruled in an ACLU case involving prison conditions in Alabama, Wallace said he would like to give the judge “a barbed wire enema.”

Judge Johnson expressed interest in Dean's argument that the layoffs in Alabama’s mental health system would deny residents a right to treatment, and said he would hold a hearing on what would constitute a right to treatment. That was when Dean decided he needed help. I put the Alabama lawyer in touch with Bruce Ennis, an attorney I had hired a few years earlier when I was director of the ACLU’s New York affiliate to launch a project on the intersection of civil liberties and mental illness. Bruce had left corporate law for the ACLU because he said he “got tired of saving millions of dollars for people I’d never met.”

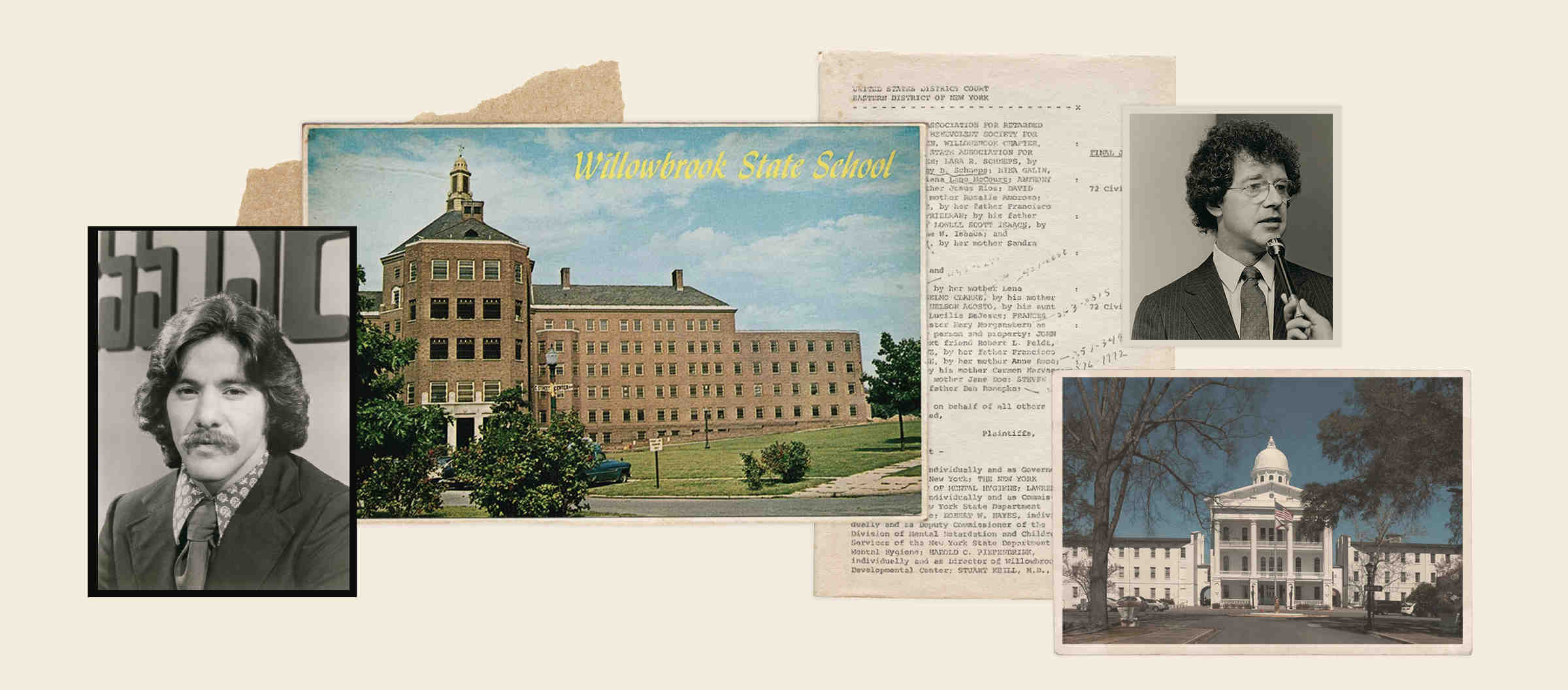

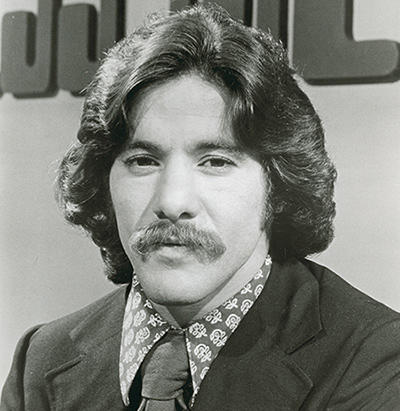

ACLU lawyer Bruce Ennis in 1981

ACLU Archives

Bruce went to Alabama to assist Dean. In the process, Bruce made a discovery. Up to that point, the litigation on which Bruce had focused involved institutions where people with mental illnesses were confined. In that era, most of those institutions were terrible places. They resembled the institutions portrayed in popular films such as the 1948 drama, “The Snake Pit,” and the 1975 Oscar winner, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

When Bruce went to Alabama, he discovered that the layoffs by the state mental health system applied not only to the state’s principal mental health hospital, Bryce, which had almost 5,000 residents. In addition, Alabama had laid off staff at Partlow, the state’s institution for people with developmental disabilities. Up to that point, Bruce had not been familiar with such institutions. What he saw at Partlow, where about 2,400 persons with developmental disabilities were confined, shocked him. Conditions were far worse than at the institutions housing people with mental illness, like Bryce.

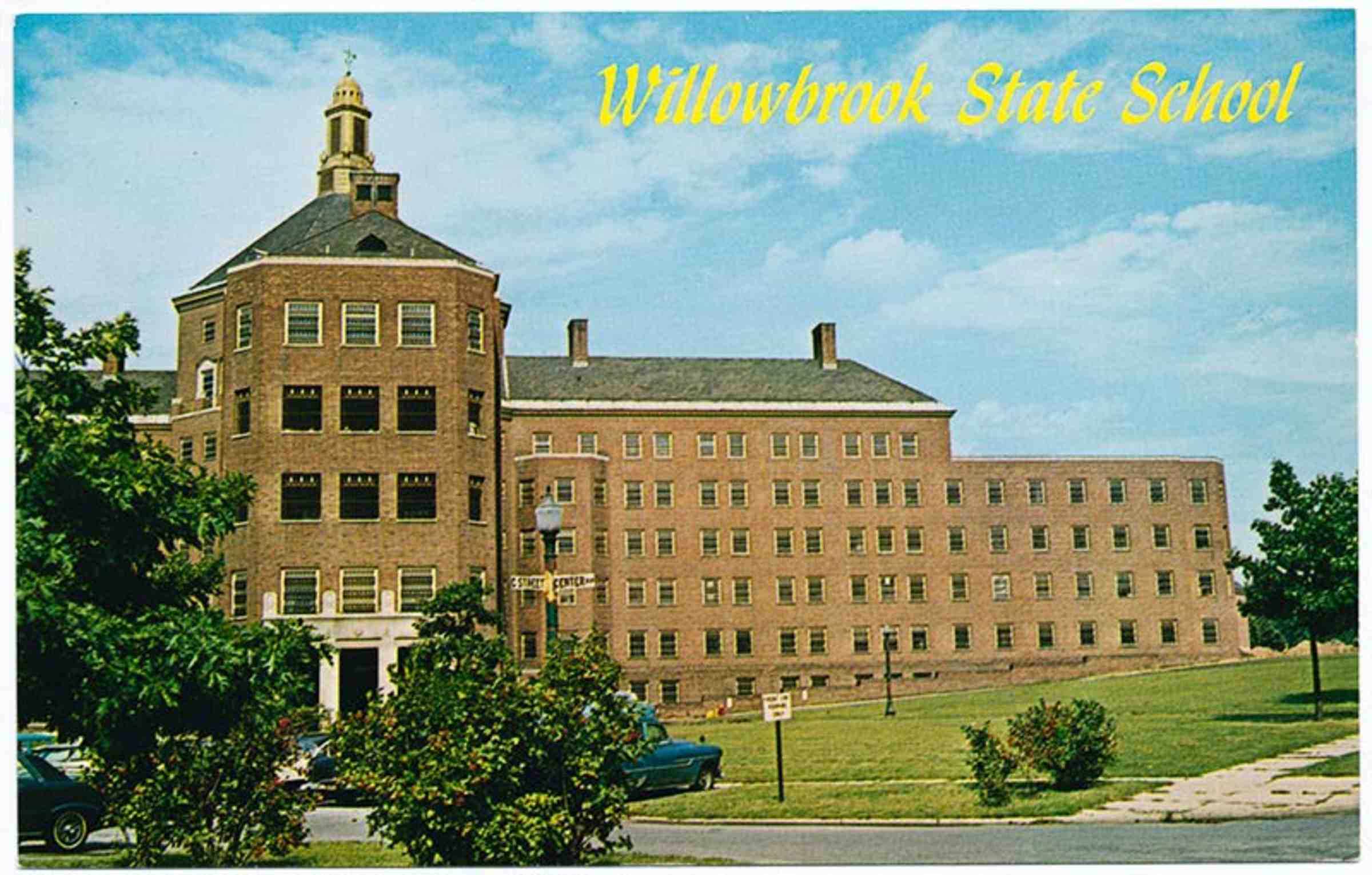

Bryce Hospital, opened in 1861 in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, is Alabama's oldest and largest inpatient psychiatric facility.

Library of Congress

Evoking Dante, Bruce summarized what he witnessed at Partlow: “Everywhere was helplessness, neglect and despair.” He continued:

There were eighty to ninety to a ward often staffed by only one attendant. Partlow was so crowded that many residents had to sleep on floor mats. The conditions were barbaric. We saw a man who had been locked in solitary confinement for seven years. A little girl was tied to her bed—otherwise she would try to stand—because there was no one to catch her if she fell. Agitated residents stuffed dirt and rocks down their throat or lapped garbage water like dogs; we saw one woman in a straitjacket trying to spit the flies out of her mouth. Helpless children lay for hours in pools of urine.

Up to that point, there had been virtually no litigation in the United States involving institutions for people with developmental disabilities. One reason was that admissions to such institutions, while generally at the suggestion of the doctor, had been at the request or with the consent of parents or legal guardians. Since such admissions were ostensibly voluntary, it was widely considered that there was no legal basis for complaints about conditions.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Bruce’s experience at Partlow inspired him to deal with the massive institution for people with developmental disabilities in the city where he lived and worked, New York.

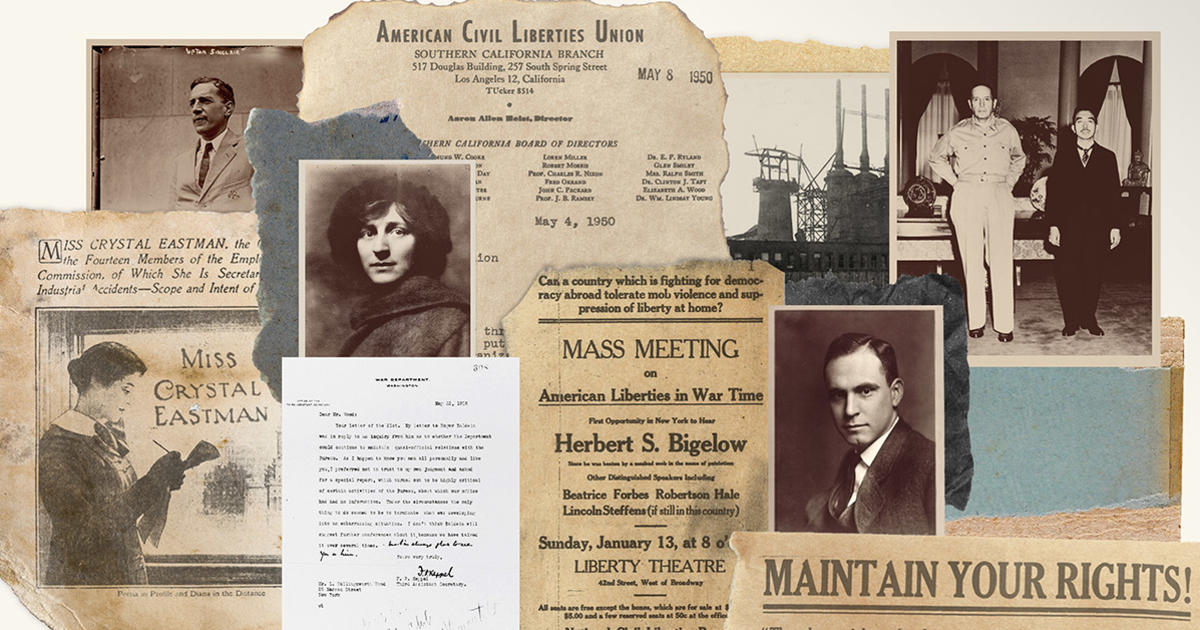

Willowbrook State School postcard

New York Public Library

“It Smelled of Death”

The Willowbrook State School, New York City’s institution for people with developmental disabilities, bore a superficial resemblance to a college campus. Opened in October 1947 by the New York State Department of Mental Hygiene, Willowbrook consisted of many buildings, most of them brick, surrounded by grassy areas and spread out on a tract of about 300 acres on Staten Island. An exterior view of Willowbrook made it seem a pleasant place. When Bruce Ennis started his efforts there in 1972, it had about 6,000 “inmates,” even though the hospital was built to house a maximum of approximately 4,000 residents.

Robert F. Kennedy

Library of Congress

Conditions inside the buildings at Willowbrook, however, were not wholly unknown. In 1965, Robert F. Kennedy, then a U.S. senator from New York, had paid an unannounced visit to the institution and denounced its conditions. Kennedy had an interest in such institutions because his sister, Rosemary, on whom a frontal lobotomy was performed at the initiative of her parents, was thought to be developmentally disabled. After visiting Willowbrook, Kennedy described the facility as a “situation that borders on a snake pit.”

Television journalist Geraldo Rivera in 1972

ACLU Archives

In 1972, about the time that Bruce Ennis was in Alabama, local ABC television journalist Geraldo Rivera had managed to get a camera into the institution for a few minutes and had broadcast some disturbing images of children wallowing in their own feces and urine. Not content with simply showing viewers the conditions, Rivera described the stench of the facility. “It smelled of filth. It smelled of disease, and it smelled of death,” he reported.

View a 12-minute clip of Geraldo Rivera's 1972 TV special about Willowbrook, courtesy PBS. (This is an important historical video. Please note that it uses language that we would currently find offensive.)

Reaching out to families of residents of Willowbrook, Bruce Ennis commenced litigation. He was fortunate to bring the federal court case he launched before Judge Orrin Judd. Judge Judd made it possible for Bruce to conduct extensive fact-finding at Willowbrook and to make arguments that helped to overcome the state’s reliance on the voluntariness of admissions as its principal defense.

Bruce persuaded Judge Judd that, even if admissions were voluntary, the state had a responsibility to protect those in its custody against harm. He argued that the consequence of confinement in Willowbrook was that those with disabilities became more severely disabled. This also implied that the state had a responsibility to mitigate the harm it had done to the residents of Willowbrook by providing them with remedial care.

Thanks in part to Geraldo Rivera, who stayed with the story, the question of what to do about Willowbrook became an issue in the political race underway for governor of New York. Rivera obtained a commitment from the Democratic candidate, Hugh Carey, that if he were elected, his first order of business would be to visit Willowbrook.

Governor-elect Hugh L. Carey delivers his victory speech just after midnight, November 5, 1974

New York State Archives

When Carey was elected in November of 1974, Bruce contacted him and offered to give him a tour of Willowbrook. Carey accepted. As they were on the tour, with Carey increasingly upset by what he saw, Bruce told him that in the next room they would enter, he would see a man tied spread-eagled to his bed. Carey asked how Bruce knew this, and Bruce told the governor-elect that he knew it because the man had been kept like that for years.

When they entered the room, Carey saw the man covered with flies. At that moment, the governor lost it. He asked, “Can’t the state of New York even afford a fly-swatter?” and abruptly discontinued the tour.

Carey directed his budget director, Peter Goldmark, to negotiate a settlement with Bruce. The highly detailed agreement they reached has governed the care provided to the residents of Willowbrook ever since. The consent decree required, among other reforms, that the institution provide its residents with clean clothes and living quarters, adequate mental health and medical care, and educational and recreational opportunities. It also called for residents to be relocated to “community placements.”

The result was that, except for a small number of residents from Staten Island itself, the Willowbrook residents were moved to smaller institutions where they were lodged temporarily. During their stay, they were housed in apartment-like settings until they could be relocated to group homes housing just a few people who lived with the help of social workers.

The process had a transformative effect.

I met one man who had been about 50 years old when he left Willowbrook. At that time, he could not dress himself or feed himself without assistance. Five years later, living in a group apartment, he not only managed his dressing and feeding, but he also held a job wrapping packages for a department store.

After Willowbrook, Bruce wasn’t done with litigation on behalf of people with psychiatric disabilities. He would go on to successfully argue O’Connor v. Donaldson (1975) before the Supreme Court for the ACLU. Bruce persuaded the high court that Kenneth Donaldson, a patient at the Florida State Hospital, should be freed and should receive damages for his unconstitutional custodial confinement. Donaldson, who was never a danger to himself or to others, had been confined for 15 years. During his confinement, he refused treatment while imploring hospital administration and staff to release him. The landmark decision affirmed that people with mental health disabilities who aren’t a threat to themselves or others cannot be involuntarily deprived of their liberty.

Ennis’ Legacy

In the wake of the Willowbrook litigation and settlement, other states moved in the same direction. The process was aided by the adoption in 1990 of the federal Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The law includes an integration mandate that holds suspect the segregation or isolation of people with disabilities. This mandate was affirmed by the United States Supreme Court in Olmstead v. L.C. (1999), in which the majority found that keeping people with mental disabilities in institutional settings when they could (and wanted to) live in the community violated the ADA.

In 1977, I was able to appoint Bruce Ennis as the ACLU’s national legal director, a position in which he became particularly known for his role in First Amendment litigation, including ACLU et al v. Reno (1997), an early case involving constitutional protection for freedom of speech on the internet. He was, I think, as able a litigator as any with whom I had an opportunity to work. Bruce was equally comfortable in a trial court as in making an appellate argument before the U.S. Supreme Court. He was also an excellent colleague — gracious, kind, and respectful to all.

Unfortunately, he died early, in 2000, at the age of 60, of leukemia.

Perhaps Bruce Ennis’s most important legacy is that many of the former residents of institutions for people with developmental disabilities in the United States, and those who might have been confined in such institutions in an earlier era, receive relatively good care today. In this respect, they differ from former residents of mental hospitals and others who have mental health disabilities.

An important factor in the difference in the care they obtain goes back to the Willowbrook litigation. Judge Judd’s finding that disability is exacerbated by confinement and that remedial care is required helped lead to the expenditure of substantial sums to provide people with developmental disabilities with care outside institutions, in small group homes, and living independently in the community.

Unfortunately, a similar system of services and supports was never created for people with mental health disabilities. While “lunatic asylums” have essentially been closed, there was never a similar investment in providing community mental health care or supported housing for people with psychiatric disabilities. In fact, federal dollars for mental health services and housing have been cut since the 1970s.

Given the number of people who are homeless with mental health disabilities, and the high rates of people with psychiatric disabilities in our jails and prisons, there are some well-intentioned persons who advocate reversion to institutionalization. What is needed, instead, is care of the sort that was provided for the former residents of Willowbrook as a result of the agreement that Bruce Ennis was able to negotiate with the state of New York.

Aryeh Neier was executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union from 1970 until 1978.