Here's How Georgia's New Voting Law Harms Voters With Disabilities

Empish Thomas is a 51-year-old voter from DeKalb County, Georgia who is blind and needs help filling out and mailing in an absentee ballot. In 2020, she was able to get that help from a sighted friend she trusted. But after the state of Georgia passed a law that made it a felony for anyone other than a “caregiver” or certain family members to help her return her ballot, she doesn’t know if she will be able to find anyone to help her vote absentee. She feels she has no choice but to try to vote in person, even though she can’t drive and has to rely on rides from others or public transportation to get to the polls.

“I believe I would be committing a crime any time I tried to have someone return my ballot because I would need to ask someone other than a family member or a caregiver,” said Empish. “The new criminal penalties are one of the big reasons I don’t feel that absentee voting is accessible to me at all.”

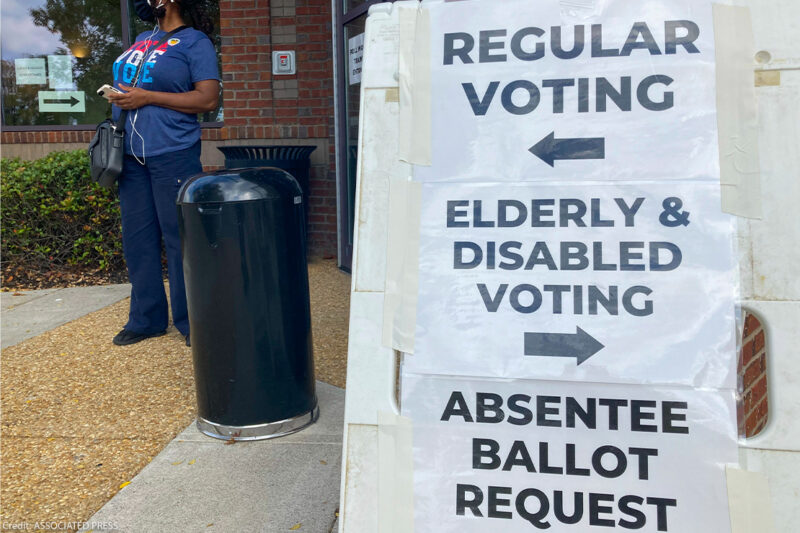

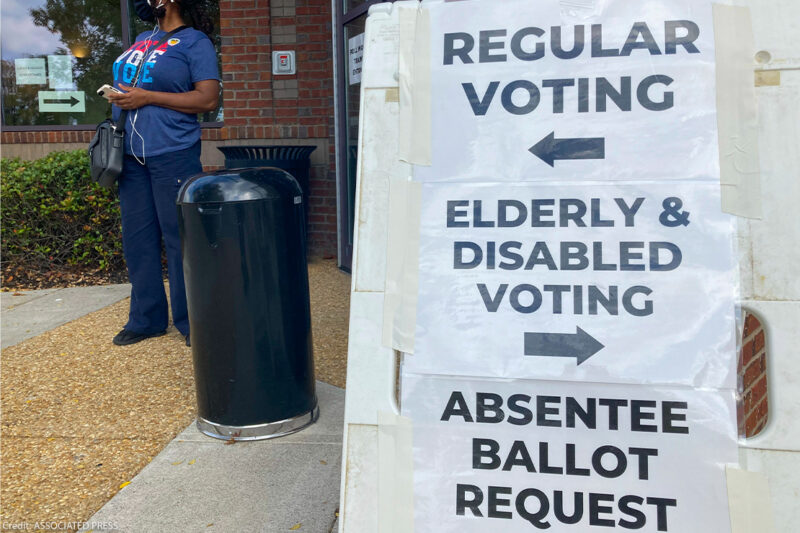

Voters with disabilities, like every American citizen, should have the same right and equal opportunity to vote. Many voters with disabilities find it more difficult or dangerous to go to the polls and vote in person, so the ability to vote by absentee ballot is crucial. But the voting law passed in Georgia in March 2021 targets absentee voting and, as a result, makes voting difficult for disabled people. That’s why this week, the ACLU and some of the nation’s leading civil rights organizations filed a preliminary injunction to stop the bill, Senate Bill 202, from disenfranchising voters with disabilities in the 2024 election cycle and beyond.

Voters with disabilities, like every American citizen, should have the same right and equal opportunity to vote.

Aspects of the bill, if left in place, violate the Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. These federal laws prohibit discrimination against people with disabilities, including imposing unnecessary burdens that effectively deny them the full and equal opportunity to access and participate in elections. The ADA and Section 504 don’t just require that people with disabilities can vote in some way — they require that states make all voting programs accessible to voters with disabilities. Voters with disabilities are legally entitled to full and equal access to Georgia’s absentee voting system, and it’s illegal to make that program burdensome or inaccessible to them, as SB 202 does.

The new voting bill puts in place a number of requirements for people who want and need to vote absentee (either by mail or by returning their ballot to a drop box). These rules hit people with disabilities particularly hard because of their reliance on absentee voting, and the preliminary injunction focuses on two of those new requirements:

First: SB 202 makes it a felony for friends, neighbors, or staff who work in shelters or nursing homes to help people receive or return an absentee ballot, even if the person has a disability. The law says that only a “caregiver” or certain family members can help with ballot return, but it doesn’t say anything about who counts as a “caregiver” under the law, and Georgia has refused to offer guidance about it.

The law creates big problems for the many disabled people who rely on friends or neighbors to help them with tasks like sending mail. For people like Empish Thomas, who has no local family members who can assist her and no one she considers a “caregiver,” this new law can make absentee voting almost impossible.

The law also makes it even harder to vote for people who live in institutional settings, like nursing homes or homeless shelters. Often, in those settings, staff help residents with sending mail, but under SB 202, those staff could be charged with felonies for providing that kind of help.

Second: SB 202 requires that ballot drop boxes be placed inside buildings and closed after business hours. Before the law was passed, most drop boxes were located outside of buildings and were available 24 hours a day.

The changes were particularly hard on Patricia Chicoine, who is 76 years old and lives in Fulton County. Because of her arthritis and knee replacements, she can’t stand for long periods of time and can’t walk more than very short distances. She even has to drive to pick up the mail from the mailbox in front of her house. Like many voters, she didn’t trust the mail, and the drop box gave her more confidence that her ballot would be counted. She was able to drive to the drop box outside her local library and used it without any problems.

But when she tried to drop off her ballot after the new law passed, things were different. She had to get out of her car and go inside the building, then walk down a long hallway to the other side of the building to find the drop box, which was very difficult for her. It took her over an hour to drop off her ballot. After that experience, she realized indoor drop boxes weren’t accessible and went to vote in person instead.

Many people with disabilities, especially those who use wheelchairs or have difficulty walking, find it much easier to use a dropbox that is outside. They can drive or walk directly to the drop box and deposit their ballot. Requiring them to go inside and find the box takes a lot of extra time and effort, and some voters with disabilities might not be able to use a drop box at all. Further, people with disabilities who rely on getting rides from others or using public transportation to get to a drop box have fewer options now that drop boxes can’t be used on evenings and weekends.

Governments should never silence or sideline the voices of disabled voters.

It is imperative that the court step in to protect the rights of the hundreds of thousands of voters with disabilities in Georgia, ensuring that they have an equal opportunity to participate in the 2024 elections. By halting the enforcement of the confusing and chilling felony provisions and permitting counties to place drop boxes outdoors, the court can restore the more inclusive voting rules that were in place before SB 202.

“When voting is accessible, I have equal access to participate in politics alongside my able-bodied peers,” said Empish. Taking that access away, she added, “is frustrating to me, because I have thoughts and views just like anyone else.”

Governments should never silence or sideline the voices of disabled voters. By advocating for a preliminary injunction, the ACLU and our partners are calling for the accessibility and equality that should be the cornerstone of our democracy. The court must recognize the urgency of this matter and act swiftly to protect the rights of disabled voters, thereby reaffirming the principles of equality and accessibility that underpin our democracy.

Donate to the ACLU

The ACLU has been at the center of nearly every major civil liberties battle in the U.S. for more than 100 years. This vital work depends on the support of ACLU members in all 50 states and beyond.

We need you with us to keep fighting — donate today.

Contributions to the ACLU are not tax deductible.