Conscientious Objectors

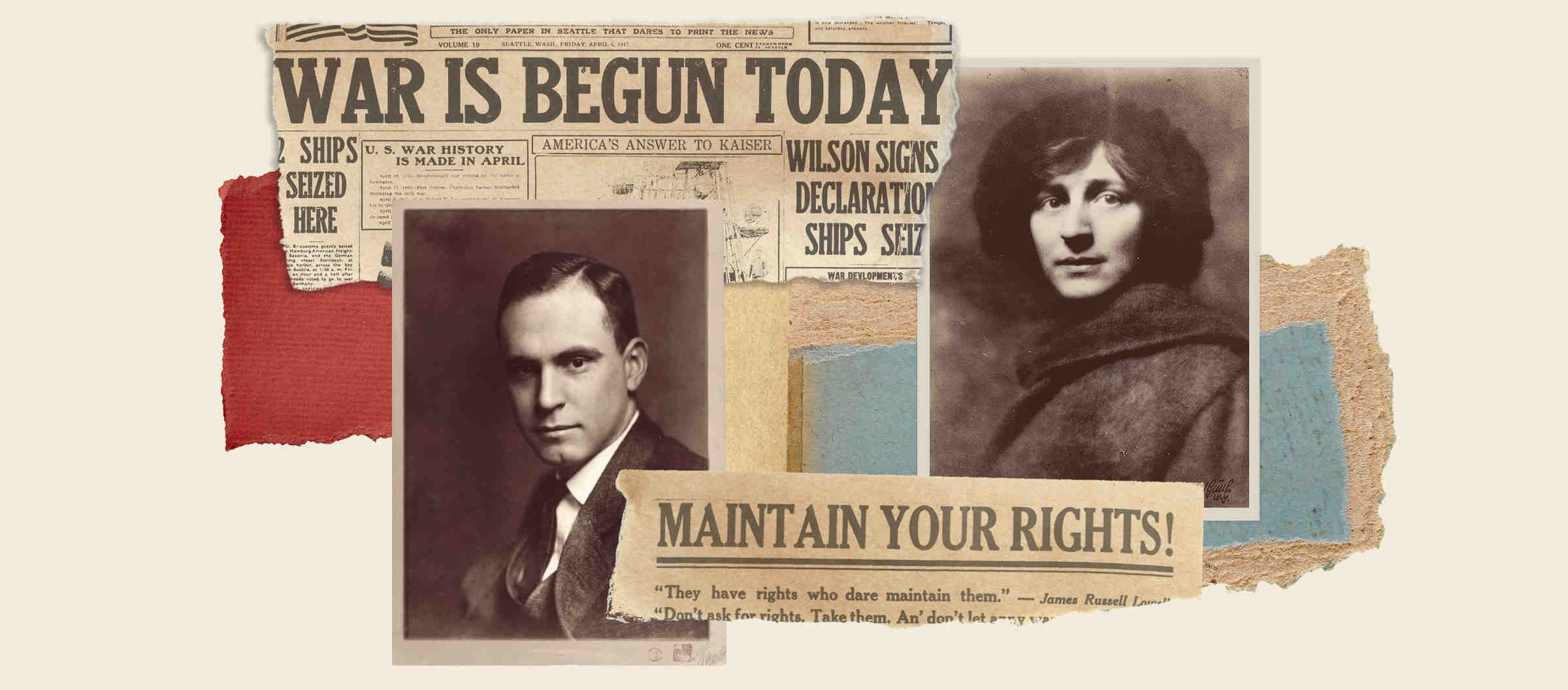

On the night of April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson made the trip from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue to the U.S. Capitol for a special session of Congress that he convened. In one of the most consequential speeches in U.S. history, President Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war that would take the country into the Great War’s killing fields in Europe. During his address that night, President Wilson called Americans to arms with the memorable pledge that “the world must be made safe for democracy.”

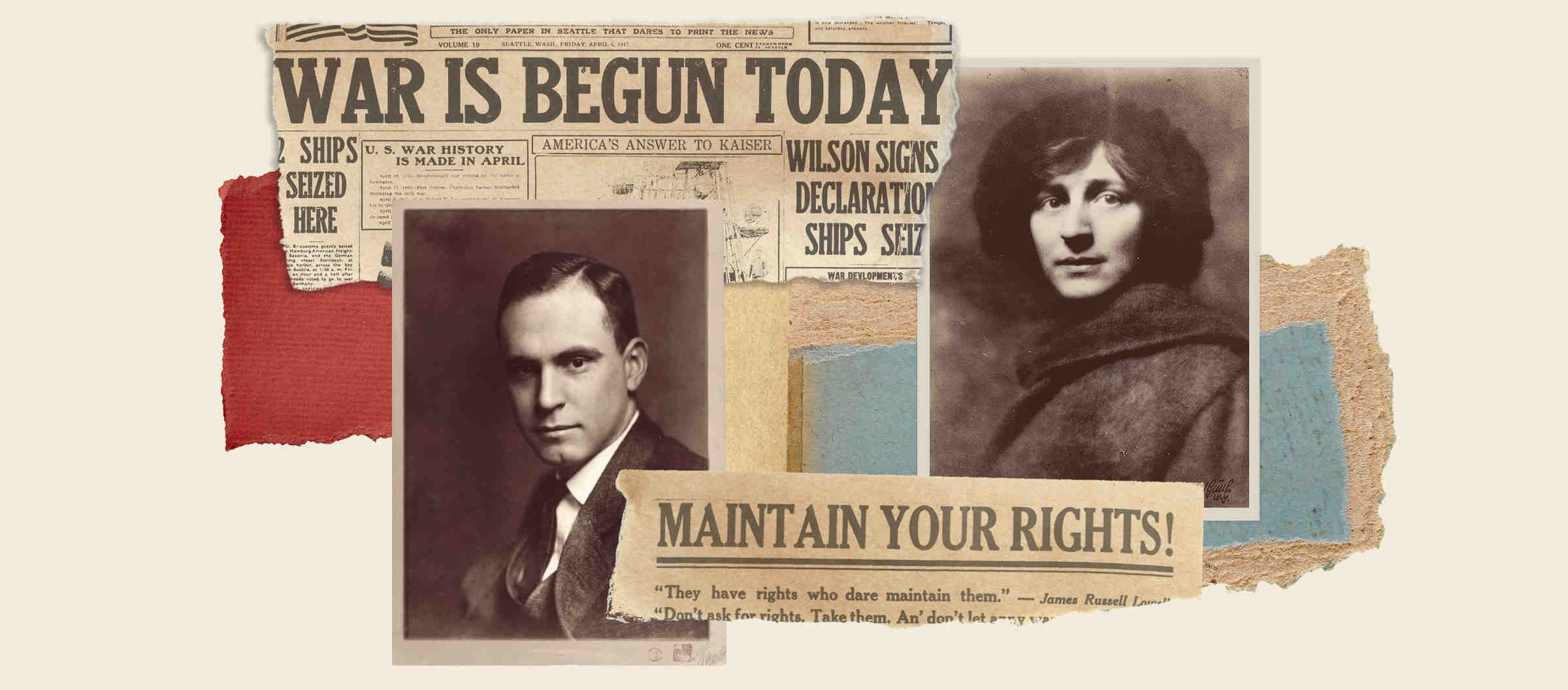

Most Americans today are familiar with the phrase, or misinterpretations of it, such as “a war to end all wars.” Few people, however, are familiar with what Wilson said next: “If there should be disloyalty, it will be dealt with a firm hand of stern repression.” In New York City, two experienced Progressive-Era activists, Crystal Eastman and Roger Baldwin, were in the office of the American Union Against Militarism (AUAM), struggling to forge a plan for how to defend the rights of Americans against the coming threats to their rights.

President Woodrow Wilson declaring war on Germany, 1917

That night would be a watershed in American history. In response, Eastman and Baldwin would found the modern movement for civil liberties with their creation of the Civil Liberties Bureau as a committee of the AUAM. For the first time, the term “civil liberties” entered American parlance as the bureau’s efforts put civil liberties on the nation’s public policy agenda. And in less than three years, Eastman and Baldwin’s small committee within the anti-war organization would evolve into the American Civil Liberties Union.

A Forceful Pair

Eastman and Baldwin already feared threats to Americans’ rights as war fever swept the country. In the months leading up to the entry into the war, Congress had debated (but not passed) a law authorizing censorship of the press. A draft of men for military service was certain, the first since the Civil War. The details of a draft were still unknown, and, most important for the civil libertarians, it was not clear what protections would be available for young men seeking conscientious objector status.

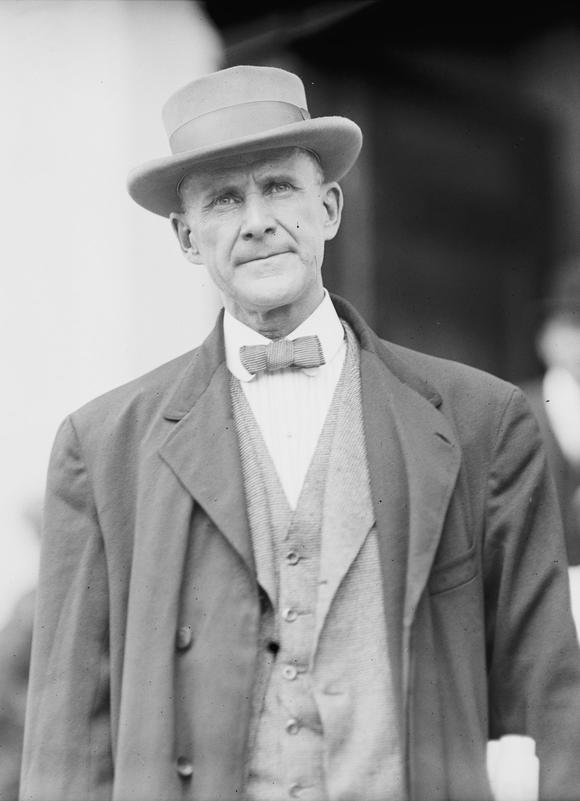

Photograph of Roger N. Baldwin, 1911

Roger Nash Baldwin Papers. Reproduced courtesy of the Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library.

Following Wilson’s speech and Congress’ declaration of war, Eastman and Baldwin worked in a crisis atmosphere, filled with uncertainty and fear, but also a good measure of confidence. They knew something new and terrifying was happening to the country they loved. The pre-war congressional debates over possible federal censorship of ideas were truly frightening. They undoubtedly knew about the 1798 Sedition Act crisis under President John Adams from their history classes, but they sensed (quite accurately, it turned out) that something far more serious was likely to happen.

Some people joined the small AUAM-CLB orbit because they were angry at what was already happening. In June, Albert DeSilver, a wealthy attorney who quit his law firm to work with the CLB, declared “my law-abiding neck gets very warm under its ‘law-abiding collar these days at the extraordinary violations of fundamental laws which are being put over.”

And while the AUAM “office” consisted of just the two of them, and with no time for much planning, Eastman and Baldwin still felt up to the challenge.

And with good reason.

Read the Entire ACLU 100 History Series

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Portrait of Eastman, ca. 1910-1915

Arnold Genthe. Reproduced courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

They were both accomplished and respected Progressive-Era reformers. Eastman had been involved in several reform efforts, graduated from New York University Law School, and published a pioneering study of “Work Accidents and the Law” in 1910. Most important, she had led the AUAM since late 1915, desperately working to keep the U.S. out of the horrific war in Europe.

As entry into the war seemed increasingly likely, she and other AUAM leaders made a last-ditch plea to President Wilson not to enter the war. Although unsuccessful, debating the president in person was, nonetheless, a heady experience that gave her confidence in the new struggle ahead.

Baldwin, from an elite Massachusetts family and a Harvard graduate, had been a social worker and progressive reformer in St. Louis since 1906. With the boundless energy he would later bring to his 30 years as director of the ACLU, he had championed electoral reforms (the initiative and the referendum), civil service reform, and racial justice (a rare position among progressives in those years). Most notably, he helped to create a juvenile court in St. Louis, and burnished his growing national reputation as the co-author of “Juvenile Courts and Probation” in 1916, the first book on the subject of this new institution.

The enormous and senseless casualties in the European war shattered his deeply ingrained optimism about social progress, and he grew increasingly alarmed as American entry into the conflict grew more likely. A week before President Wilson’s address, he abruptly dropped all of his St. Louis activities and went to New York City to join Eastman at the AUAM.

The Attack on Dissent

Events quickly confirmed and even exceeded Eastman and Baldwin’s worst fears.

Fired up with patriotism, mobs of Americans across the country began attacking anti-war meetings and demonstrations. Fights among pro- and anti-war groups broke out in front of Congress even as the president made his case for war. Congress passed the Selective Service Act on May 18, providing conscientious objector status only to members of well-recognized religious groups whose tenets required pacifism, which meant members of the three “historic peace churches” — the Quakers, Mennonites, and the Brethren. Young men of conscience who were members of mainstream faiths — Methodists, Catholics, Presbyterians, Jews — would be forced to fight and kill in violation of their beliefs.

A month later, Congress passed the Espionage Act, which in very elastic language made it a crime to obstruct the military effort, including the draft. In July, the Post Office began declaring a broad swath of anti-war publications “unmailable” and barring them from the mails. Banned materials included the Socialist Party’s newspaper, foreign language papers (especially German and Russian), and even pamphlets issued by the new Civil Liberties Bureau.

Eugene V. Debs

At the heart of the repression of dissent was the fact that the Justice Department and the Post Office interpreted “obstruct” very broadly to include almost any language that appeared to oppose the war, the draft, or both. In fact, Eugene V. Debs was convicted and sentenced to 10 years in prison for a speech in which he did not even mention the current war or the Wilson administration. He simply gave a generic socialist critique of capitalism for fostering wars.

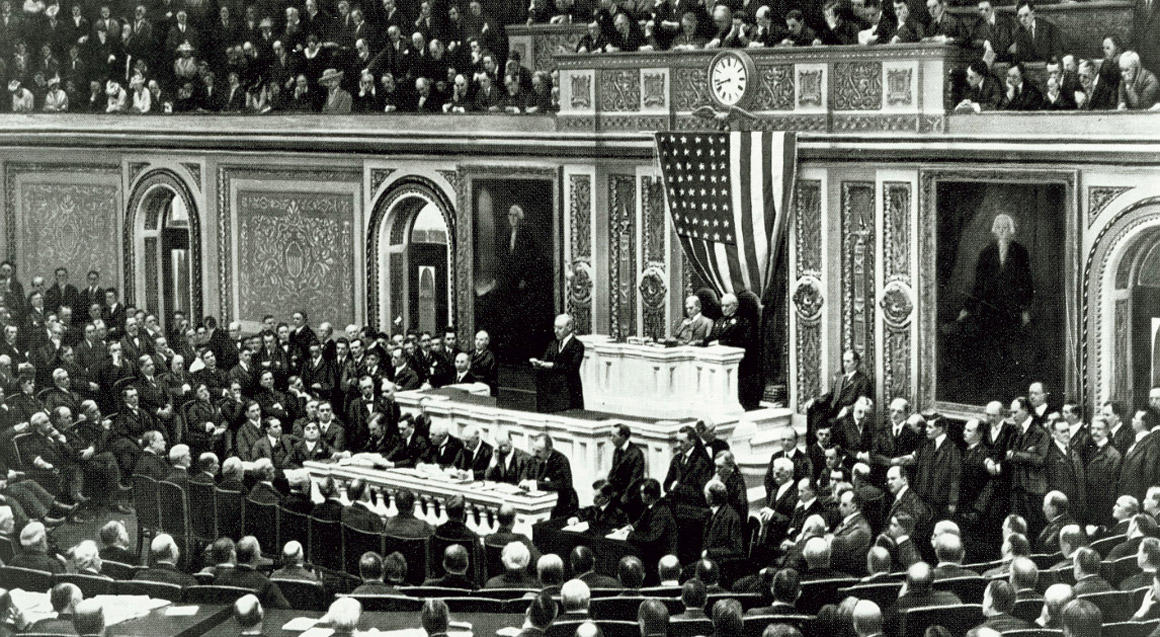

The Civil Liberties Bureau quickly began issuing a series of pieces on its mission of defending free speech and providing information about the draft. One of the first explained its “War Program,” followed by “Concerning Conscription,” “Maintain Your Rights,” and “Constitutional Rights in War Time.” By November, as vigilante attacks on war opponents, socialists, and suspected draft evaders were occurring nationwide, the bureau issued a report on “Mob Violence and the Law.” Regarding the draft, the bureau argued that the draft had been a failure in the Civil War, that volunteers made better soldiers than draftees, and that the law was unconstitutional (the Supreme Court contemptuously rejected this argument in a suit filed by others in early 1918).

Roger Baldwin, meanwhile, soon established correspondence with the War Department over the issues related to conscientious objectors. Civic leaders had been frequent dinner guests of his parents, and dealing with influential people came naturally for him (and he had used this talent well in his St. Louis activities). His contact was Frederick C. Keppel, who had taken leave as dean at Columbia University to become Third Assistant Secretary of War. Keppel also had a strong progressive reform record and had been active in the leading international peace organization before the war.

Baldwin and Keppel maintained a productive dialogue over the treatment of conscientious objectors — for about 10 months. In early 1918, authorities in the War Department and the Justice Department concluded that the Civil Liberties Bureau’s criticisms of the administration interfered with the war effort and the draft in particular. Keppel wrote Baldwin that corresponding with him had become an “embarrassment” and severed their relationship. Military intelligence began spying on those involved with the Civil Liberties Bureau, and far worse would soon come.

The Civil Libertarians vs. Progressive-Era Reformers

In the first months of the war effort, Eastman and Baldwin were not only alarmed by the government’s actions but were truly shocked and dismayed by the actions of their fellow prewar progressive reformers.

“If there should be disloyalty, it will be dealt with a stern hand of repression.”

President Wilson

Virtually all of the leading reformers enthusiastically endorsed the war effort as a grand calling and many volunteered in one of the many service organizations that quickly sprang up. President Wilson’s vision of a world made safe for democracy was intoxicating to these social activists. George Creel, a crusading progressive-minded journalist, became director of the government’s propaganda agency, the Committee on Public Information. Carrie Chapman Catt, a leader of the National American Suffrage Association, put aside her pacifist principles and joined a national service organization. John Dewey, already America’s most noted philosopher, wrote an article arguing that the war effort created great opportunities for social reform.

By May 1917, Eastman and Baldwin found that they were members of a small and very isolated group of Americans who were willing to challenge the administration over issues of free speech and press as well as freedom of conscience for young men opposed to participating in war. But an even greater shock awaited them in June.

A Defining Moment

Lillian Wald, the highly respected reformer and co-chair of the AUAM, informed Baldwin in June that, “We cannot plan continuance of our program which entails friendly government relations, and at the same time drift into a party of opposition to the government.”

Baldwin was stunned.

Wald, a committed pacifist who had opposed the U.S. entering the war, was now telling him the AUAM could not tolerate the Civil Liberties Bureau’s criticism of the government. He and Eastman would have to cease their criticisms of the violations of free speech and press, along with their defense of conscientious objectors. It was nothing less than a betrayal of fundamental principles.

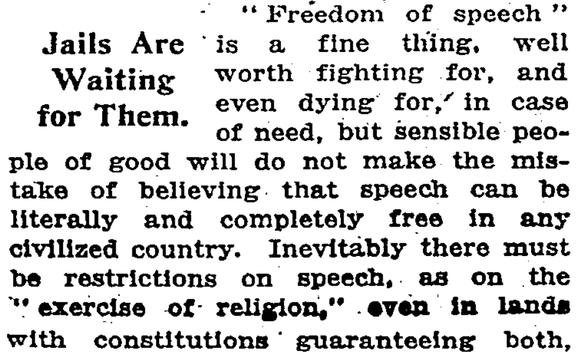

New York Times Excerpt (July 4th, 1917)

After some back and forth, the two sides reached a settlement. On July 1, the Civil Liberties Bureau would leave the AUAM and become an independent organization: the National Civil Liberties Bureau.

The New York Times greeted the NCLB with an ominous July 4 editorial entitled, “Jails Are Waiting for Them.”

The split with the AUAM and the creation of the NCLB marked the real birth of the civil liberties movement in America.

Eastman and Baldwin took a stand on a principle that became the guiding star of the ACLU:

The principled defense of civil liberties without compromise based on political considerations.

Over the next 100 years, the principle guided the ACLU through a continuing series of difficult policy decisions: defending the right of the Ku Klux Klan to march in Boston in 1923, despite criticisms from liberals and civil rights advocates; the defense of free speech for domestic Nazi groups in 1935, despite opposition from some ACLU board members and liberals around the country; opposing the evacuation and internment of the Japanese-Americans in World War II, in the face of near total public support for the government’s action. And the list continues to grow today.

The NCLB Carries On — and Becomes an Outlaw

The NCLB carried on the fight for civil liberties through the rest of 1917 and into 1918. Eastman largely withdrew because of health problems, leaving Baldwin as the driving force. The group denounced mob attacks on war opponents; criticized the prosecution of anti-war leaders under the Espionage Act like Debs; and published a report on the virtual destruction of the radical labor union, the Industrial Workers of the World (“The Truth About the IWW”), by a combination of vigilante attacks and federal prosecution.

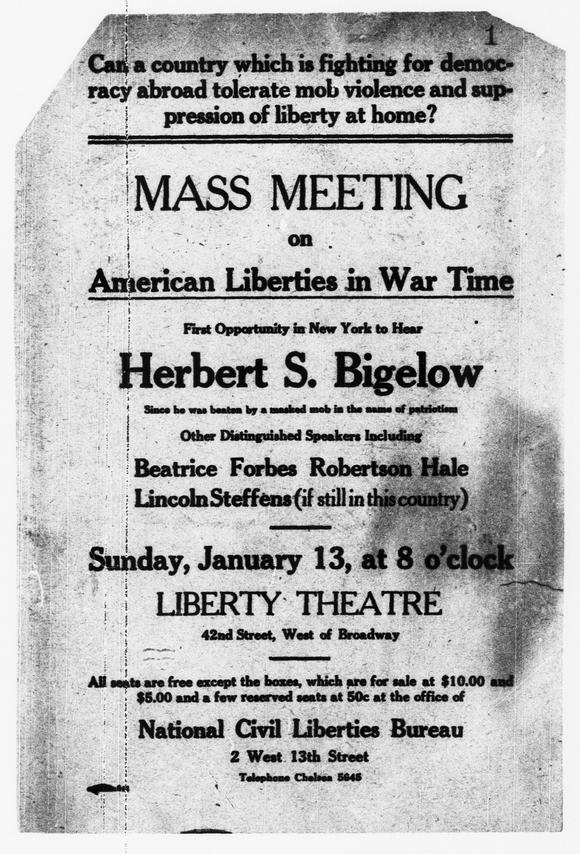

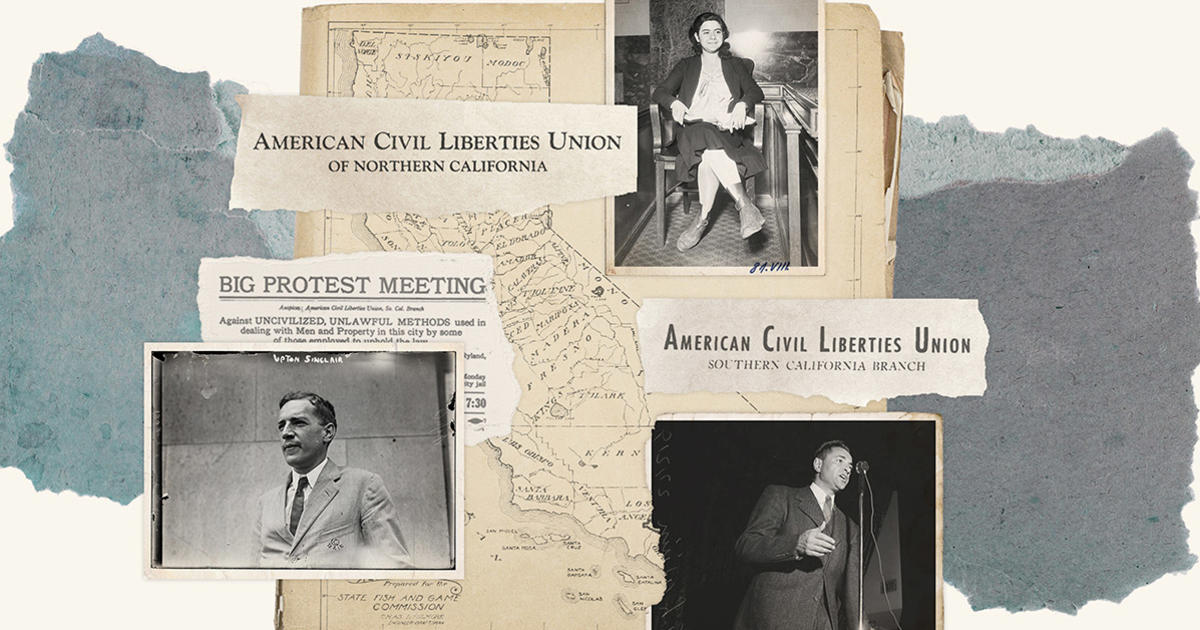

Correspondence-Organizational Matters; Conferences, Mass Meetings; American Civil Liberties Union Records: Subgroup 1, The Roger Baldwin Years, MC001.01, Public Policy Papers, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Libraary

To publicize the wave of attacks on dissenters, the NCLB organized a mass meeting in New York City in early 1918 featuring Herbert Bigelow, a Cincinnati socialist and progressive activist who had been kidnapped, stripped, and beaten by a vigilante group. The anti-dissent hysteria was so fevered that a person’s actual views did not matter: Bigelow had actually quit the Socialist Party because he supported the war. The size of the meeting and the publicity it generated was the last straw for the Wilson administration, however, and its instruments of repression began targeting the NCLB.

The Military Intelligence Section office in New York City began spying on Baldwin and the NCLB, even burglarizing the office and stealing some of the group’s records. Baldwin was then summoned for an interrogation in March. Failing to grasp the hostility of his questioner, Baldwin foolishly proposed a compromise, in which he offered to cease any activities the government opposed, and, in a shocking move, offered to let the government see its lists of its members and financial contributors. This shameful action exposed people on those lists to possible prosecution under the Espionage Act.

The government finally struck in late August, raiding the NCLB office and carting off all of the organization’s records as part of a set of raids on anti-war groups around the country.

Baldwin was completely unhinged, moving around the office telling federal agents they could “lock him up, shoot him, hang him, or anything else,” according to an agent’s report. Prosecution of NCLB leaders now seemed certain. For reasons that are not clear, however, no one was prosecuted and the war in Europe ended two months later.

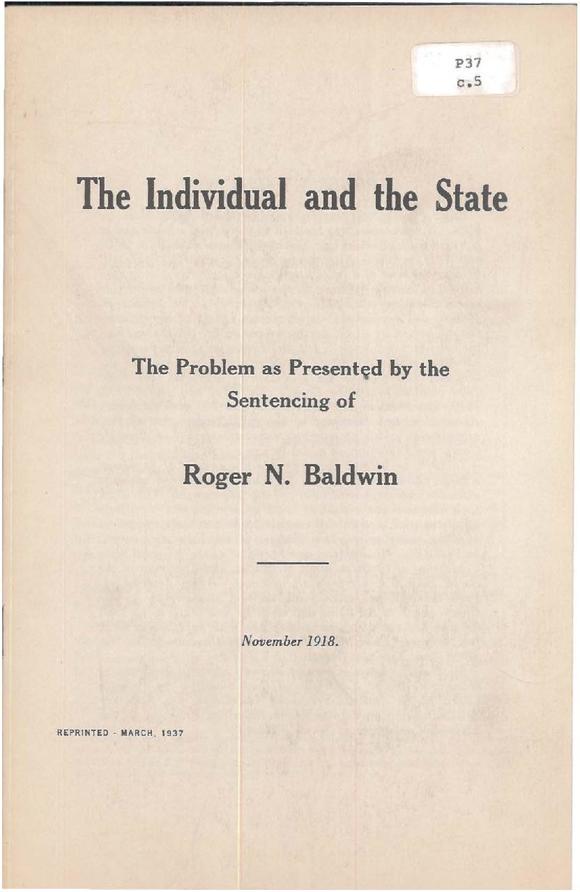

'The Individual and the State'

Baldwin, meanwhile, had a new and very personal problem. Needing more troops, the government raised the draft age to 35, covering the 34-year-old civil libertarian. When he received his draft notice, Baldwin thought deeply about his situation and finally decided that as a principled conscientious objector he would not cooperate in any way with the draft. (Other young men who chose this course of action were known as “absolutists.”) Consequently, he by-passed his draft board and presented himself directly to the prosecutor. He was duly convicted on October 30, 1918, and sentenced to a year in jail.

Baldwin’s day in court became a singular and highly publicized event. With the court room filled with his friends and colleagues, he delivered to the judge a speech explaining his motives and declaring his “uncompromising opposition to the principle of conscription of life by the State for any purpose whatever, in time of war or peace.”

The conservative Judge Julius Mayer was struck by this man of principle, and he felt compelled to say so. “You do stand out [from other defendants] in that you have retained your self-respect,” Mayer told Baldwin from the bench. “You are entirely right. There can be no compromise” of basic principles. But the judge said he could not compromise either, and so Mayer sentenced this remarkable defendant to a year in jail. Baldwin’s friends quickly published Baldwin’s statement, titled “The Individual and the State,” along with Judge Mayer’s response. The statement circulated widely and became a classic in pacifist circles.

Read the full text of The Individual and the State here.

Prisoner #254 in the Essex County, New Jersey, jail (where short-term federal prisoners were held) turned his sentence into what he called his “vacation on the government.” He used his time to read and think about his personal future and the future of the country, particularly about the problem of individual rights in a modern urban-industrial society.

The Creation of the ACLU

Baldwin was released from jail in mid-July 1919. He probably already had a plan for his future, but first he wanted to take care of some personal business. Feeling he needed some personal experience as an industrial worker, he embarked on a trip that took him to Pittsburgh and St. Louis, working for a brief period in a steel mill. With that taken care of, he returned to New York and set about creating a permanent organization to defend civil liberties. In addition to most of the core group from the NCLB, he enlisted a broader range of people from labor and radical or left political circles.

Those who joined the proposed new group had no illusions about the challenge they faced. All the agencies of the “machinery of justice,” as they called it, were controlled by powerful business interests. The general public had been cowed into silence by vigilante violence and government prosecutions. Not a single court decision anywhere afforded protection for freedom of speech, press, or assembly. A series of race riots in 1919 in Washington, D.C.; Chicago; and Omaha, Nebraska (among other cities) indicated that racism was thoroughly entrenched, even outside of the segregated South. In the South, moreover, lynching of African Americans averaged slightly more than 60 a year. The prospects for civil liberties, in short, could not have been bleaker.

And so, in this seemingly hopeless situation, on Jan. 19, 1920, the executive committee of the new American Civil Liberties Union held its first official meeting. The fight for civil liberties was on.

Matters of Principle

In the early days of the ACLU, the California branches helped maintain the organization’s radicalism as the national organization became more and...

Source: American Civil Liberties Union