Judge Says New Hampshire’s Ban on ‘Ballot Selfies’ Violates the First Amendment and ‘Common Sense’

UPDATE: The state appealed our win in this case, and oral argument in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit is being held on September 13, 2016.

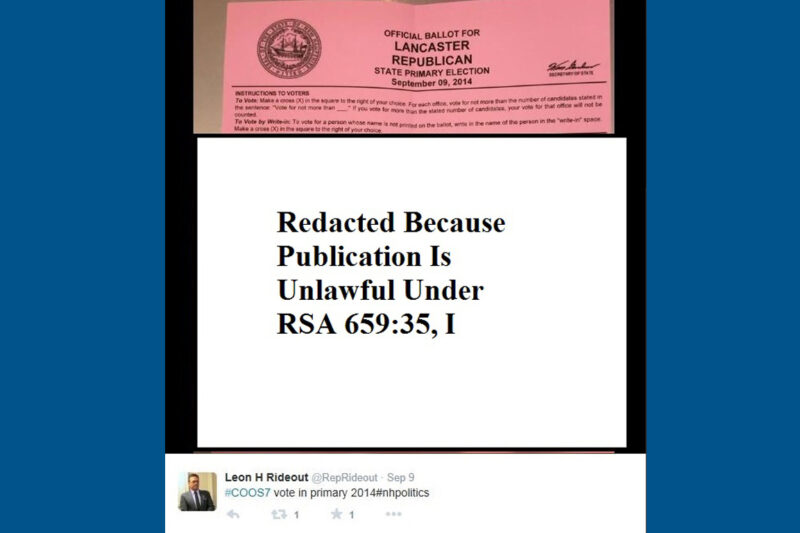

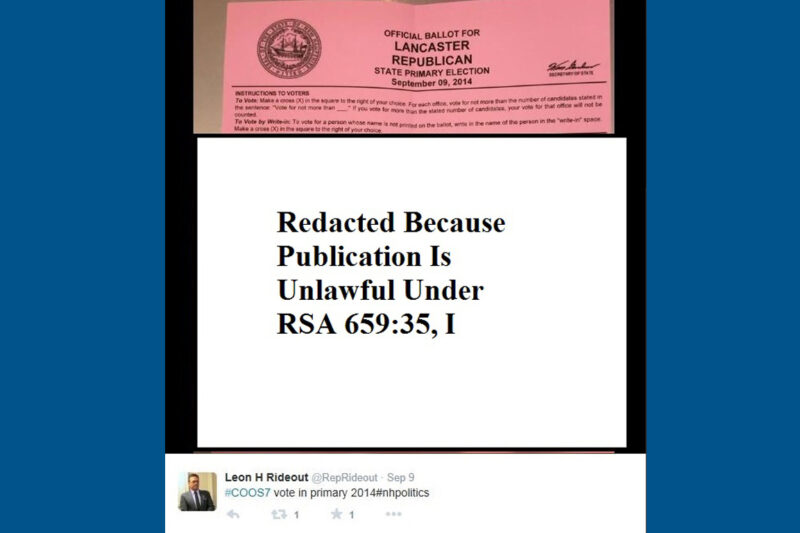

Andrew Langlois lives in Berlin, a small city in northern New Hampshire with a population of 10,000. During the September 2014 primary election, Andrew, who was frustrated with the Republican candidates for U.S. Senate, wrote the name “Akira” as a write-in candidate. Akira was the name of Andrew’s dog that passed away just days before the primary election.

Andrew snapped a photograph of the ballot’s U.S. Senate section with his phone. He then cast his ballot and went home. He later posted the photograph on Facebook, along with commentary reflecting his frustration with his Republican choices for U.S. Senate.

After the election, Andrew received a call from an investigator at the New Hampshire Attorney General’s Office. The investigator told Andrew that he was being investigated for posting a photo of his marked ballot on social media in violation of New Hampshire law.

Yes, you heard that right. New Hampshire was investigating Andrew for engaging in political speech on the Internet.

Andrew ran afoul of a New Hampshire law, enacted in 2014, that bans a person from displaying a photograph of a marked ballot reflecting “how he or she has voted,” including on the Internet through social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. Under the quickly dubbed “ballot selfie” law, willfully engaging in this form of political speech is a violation-level offense punishable by a fine of up to $1,000.

This New Hampshire case is yet another reminder that we must remain vigilant against attacks on online speech.

After hearing Andrew’s story, the ACLU of New Hampshire filed a lawsuit in federal court on behalf of Andrew and two other voters — including a member of the New Hampshire legislature — challenging the law as violating the First Amendment.

On August 11, 2015, a federal judge struck down the law, ruling that the law “deprives voters of one of their most powerful means of letting the world know how they voted.” For example, this form of speech can convey a sense of pride and excitement from an 18-year-old, newly minted voter who is enthusiastic about voting in her first presidential selection. It can convey, as it did with Andrew, the message of political protest against one’s choices for public office. The court understood that these messages lose their salience without the photograph of the marked ballot.

Unfortunately, this New Hampshire law is part of a national trend.

The digital revolution has produced the most diverse, participatory, and amplified communications medium humans have ever had: the Internet. As this medium has become more pervasive in society, state legislatures have passed laws restricting how every day citizens can use the Internet. This has included attempts to create new decency restrictions for online content, limit minors’ access to information on the Internet, or allow the unmasking of anonymous speakers without careful court scrutiny. Though well intentioned, these laws often have the unintended consequence of suppressing innocent speech protected under the First Amendment.

The New Hampshire legislature’s idea behind its ban on ballot selfies was to prevent illegal vote buying and voter coercion. But the law had one huge problem. Rather than limiting the law’s reach to online displays of marked ballots linked to these illegal schemes, the law banned innocent displays of marked ballots on social media — speech which is almost always political in nature.

As United States District Judge Paul Barbadoro wrote: “[T]he means that the state has chosen to address the issue will, for the most part, punish only the innocent while leaving actual participants in vote buying and voter coercion schemes unscathed.” But he wasn’t finished, adding, “both history and common sense undermine rather than support the state’s contention that vote buying and voter coercion will occur if the state is not permitted to bar voters from displaying images of their completed ballots.”

Put another way, the First Amendment does not allow states to broadly ban innocent political speech with the hope that such a sweeping ban will address underlying criminal conduct.

This New Hampshire case is yet another reminder that we must remain vigilant against attacks on online speech. If First Amendment protections are to enjoy enduring relevance in the 21st century, they must apply with full force to speech conducted online and through social media platforms, especially where this speech is political in nature.