Louisiana passed a law this year that is a foolhardy attempt by one state to regulate the Internet. By doing so, the state’s lawmakers threaten the First Amendment rights of adult publishers and readers, as well as minors, because it censors valuable speech. And despite these troubling impacts, the law is totally ineffective in its stated purpose — protecting minors from seeing “harmful” material online.

The law makes it a crime to publish anything on the Internet that could be deemed “harmful to minors” without verifying the age of everyone who wants to see it. If you are in Louisiana, and publish anything on the Internet, you have to either make sure that none of that content could be considered harmful to a minor of any age — a high bar, considering a lot of constitutionally protected speech might not be fit for an 8-year-old — or install an age-verification screen asking if the viewer is 18 or over before allowing access.

If you don’t, it’s a crime.

That’s why the ACLU, the ACLU of Louisiana, and the Media Coalition filed a lawsuit in November challenging the law as unconstitutional on behalf of Louisiana bookstores, magazines, and members of the American Booksellers Association and Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. Today we filed a request for a preliminary injunction asking a federal court to block the law, which presents an ongoing threat of self-censorship by Louisianans who use the Internet.

There are a number of problems with such a law. In the first place, it is ineffective, because it doesn’t actually prevent any teenager from viewing any website published outside Louisiana — which constitutes the vast majority of Internet content — harmful or otherwise. That means that Louisiana is limiting the expression of its own residents for no good reason.

Additionally, there is a wide swathe of material that is not obscene — and therefore constitutionally protected — but which some people might consider harmful to some minors, especially younger ones. A wide range of books and materials on sexual and reproductive health that are not only appropriate for, but indeed targeted at, older teenagers might be considered harmful to a 10- or 12-year-old in some communities in Louisiana. But the law makes no distinction between these categories. So a teenager who wants to visit a Louisiana website hosting content about teenage sexuality will be unable to do so unless she is willing to falsely attest to being 18 or over, which can constitute a separate crime under Louisiana law.

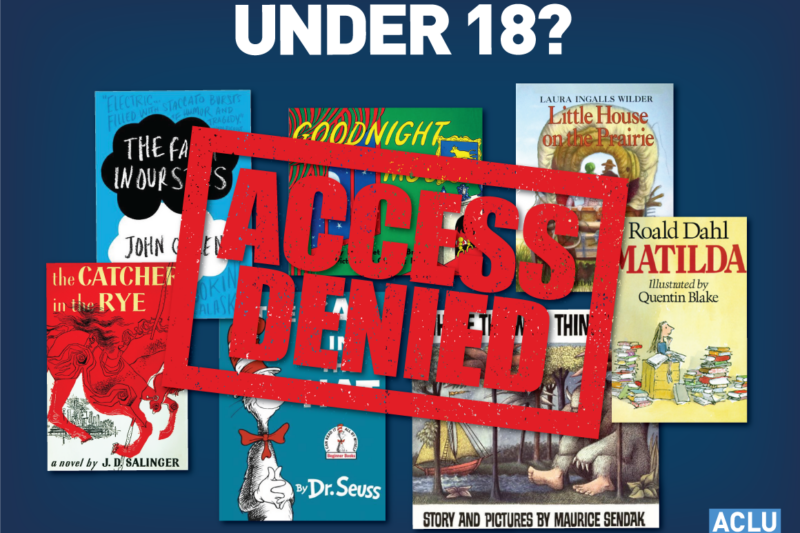

Not to mention that what is considered “harmful” is in the eye of the beholder. For example, a book such as “The Catcher in the Rye” might be considered classic literature in a high school syllabus, or it might be the target of a local school board’s outrage. The same goes for “The Color Purple,” “Beloved,” or “Slaughterhouse Five” — all books that have, alternately, been either assigned as required reading or banned for sexual content.

The law even sweeps within its ambit material that could not conceivably be harmful to any minor at all. For example, some Louisiana bookstores sell books online through national, third-party databases that offer millions of books for sale. Small, independent bookstores such as our plaintiffs do not have the resources to review millions of book listings to determine which must be restricted for minors. As a result, they may be forced to place their entire inventories behind an age-verification screen, creating the absurd result that a 17-year-old who wants to purchase a copy of Little House on the Prairie for a younger sibling on the bookstore’s website can’t do so.

The law is written so broadly, in fact, that it would seemingly cover things such as Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram posts by people in Louisiana, even though they have no way of controlling who sees their social media posts. People in Louisiana may be afraid to put up material that is even potentially within the scope of the law in order to avoid criminal liability.

While the state may have a legitimate interest in protecting minors from things like online pornography, there are better ways to do that, and this law suppresses far more speech and impacts everyone’s First Amendment rights.