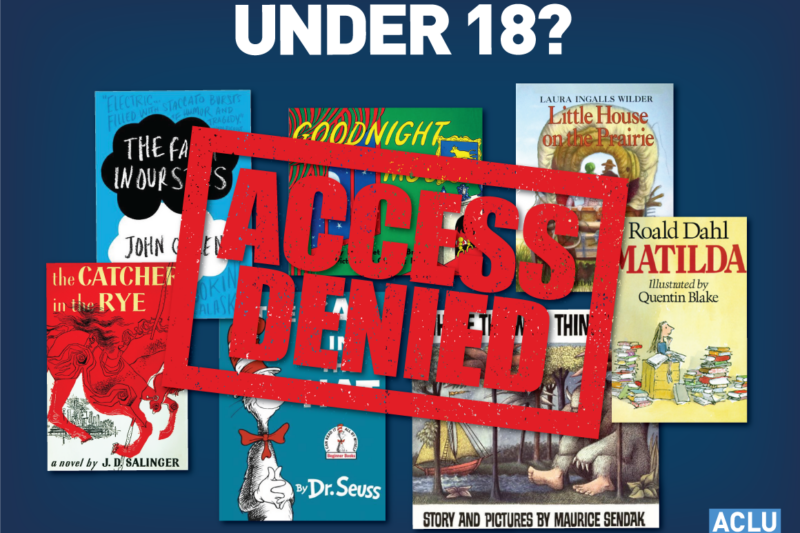

Before Friday, a Louisiana bookstore might have feared prosecution for allowing a teenager to browse a book like “The Catcher in the Rye” on its website.

But no longer! A federal judge has blocked a harmful Louisiana law that would make it a crime to publish anything on the internet that could be deemed “harmful to minors” without verifying the age of everyone who wants to see it. In explaining its injunction against the law, the court rightly noted that the law likely violates the First Amendment because it creates the risk of self-censorship and chills the exercise of free speech rights.

The Louisiana law has numerous problems. For starters, material that may be considered harmful to a 12-year-old may be appropriate for a 17-year-old — yet the law requires internet publishers to bar access to such material to anyone under 18. Additionally, the law seemingly covers materials published on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram, requiring anyone in Louisiana who uses social media to verify the ages of everyone who views their posts, even if their accounts are private and they know that no minors have access.

The lawsuit was brought by the ACLU, the ACLU of Louisiana, and the Media Coalition on behalf of Louisiana bookstores, publishers, and members of the American Booksellers Association and Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. All of the plaintiffs publish a wide swathe of materials that are not obscene but which might be considered harmful to minors, especially younger minors.

Consider some of the dilemmas our clients faced when the law was passed. For example, what should a Louisiana bookstore do if it stocks thousands or millions of titles, including such books as the “Joy of Sex” or “The Catcher in the Rye,” which (depending on the perspective) could be considered harmful to minors? Should it simply bar minors from seeing anything on its site, including children’s books? Or should it take down all the books that could be considered harmful to minors, depriving adults of access to them?

The law is also completely ineffective, as the court recognized, because it cannot prevent teenagers from seeing materials published on the internet from outside Louisiana. (Not to mention teenagers could always pretend to be older than they are, which could constitute a violation under a separate Louisiana law.) And while the state argued that the burden on a website is lessened because it could circumvent the law’s age-verification requirements by having an individual physically outside the state upload any harmful-to-minors material to its website, that interpretation makes the law even less effective.

In other words, the law would do nothing to actually keep harmful material out of reach of minors in Louisiana, but instead simply imposes burdens on speakers — like bookstores and publishers — in the state.

The court rightly found that to avoid criminal prosecution, the plaintiffs might be inclined to apply the age-verification process in an unnecessarily broad manner, or stop publishing materials that could be deemed harmful to minors. “A possible consequence of the chill caused by [the law] is to drive protected speech from the marketplace of ideas on the Internet,” the opinion reads.

It’s our hope that the state recognizes the wisdom of this ruling and refrains from appealing. It makes no sense — legal or otherwise — for bookstores, publishers, or any Louisianans to fear criminal prosecution for speaking freely on the internet.