No Human Rights On The High Seas

As darkness fell upon the Caribbean Sea off the coast of Haiti, Robert Weir was chained by his ankle to the deck of an unfamiliar ship. Just hours earlier, he and his crewmembers had been on board the Jossette, their small commercial fishing boat. They had gotten lost while on a two-day fishing trip and were trying to find their way home to Jamaica. But now he and his mates were shackled to metal cables on the deck of a U.S. Coast Guard ship, hundreds of miles from home.

“And gradually when it's…dusk…we see a big fire,” said Weir. “They light the boat…and then watch it burn…till we no see no more fire.” Weir and his mates watched in disbelief as a Coast Guard officer fired a flare at the Jossette. The boat burst into flames and then sunk after Coast Guard officers riddled its hull with bullets. Shortly afterward, the Coast Guard ship set sail in an eastward direction. Although they did not know it then, this would be the beginning of more than a month of brutal detention with no contact with the outside world.

Robert Dexter Weir, Patrick Wayne Ferguson, Luther Fian Patterson, and David Roderick Williams are all Jamaican citizens and lifelong fishermen. “I've been a fisherman from when I was about 8 years old. Almost all my life I've been a fisherman,” Weir said. For years, the men fished all over Jamaican waters, making a decent living for themselves and their families.

Luther Patterson, Robert Weir, Patrick Ferguson

On the night of Sept. 13, 2017, the men left the Half Moon Bay fishing village aboard the Jossette, bound for Morant Cays, an offshore island group located in Jamaican territorial waters and a well-known fishing spot at that time of the year. They informed their families that they’d be back in a couple of days after retrieving fish from traps that they had set in the waters surrounding the cays a few days before. This simple fishing trip would soon prove to be anything but routine.

“…We reach a certain distance, then the weather get bad,” Ferguson said. Several hours after leaving Half Moon Bay, a storm unexpectedly blew up. The Jossette’s main engine lost power, and, reduced to one 75 horsepower engine, the boat drifted off-course in the stormy seas. At first light on Sept. 14, the crew realized that they had over-shot the Morant Cays and were lost. They decided to head toward a landmass they saw far in the distance so they could get their bearings and find their way home. The men did not know that the landmass was Haiti.

Around noon, as the men inched toward land, they saw something in the distance. “We see this vessel up in the sunlight coming down on us,” Weir said. The United States Coast Guard ship Confidence had spotted the Jossette. They dispatched four armed officers in a high-powered speedboat to stop, board, and search the Jossette and its crew. The officers wrongly believed that the boat and its crew were involved in drug trafficking.

The crew of the Jossette realized it was the Coast Guard only when the speedboat pulled right alongside them. “They told us to hold up our hands and face to the front of the boat with our arms bent over. And we do what they say,” Ferguson said. The officers then began peppering the men with questions about who they were and what they were doing in that part of the Caribbean Sea. They said they were fishermen from Jamaica who were lost and trying to find their way back home. They provided identification for themselves and registration documents for their boat.

The Coast Guard officers were not satisfied. They searched the boat and the men for hours, using a high-tech detection device in their exhaustive search for drugs. But they found no marijuana or traces of marijuana on the boat or on the men. Undeterred, the officers told the men that they were transporting them to the Confidence, where they’d be detained. The officers did not explain why. “They pointed guns at me, they said go on their boat,” Ferguson said.

Once aboard the Confidence, the Coast Guard officers ordered the men to strip naked. They then gave each of them paper-thin coveralls and a pair of thin, disposable slippers to wear instead. The officers then marched the men toward the bow of the ship, where they chained each of them by one of their ankles to metal cables that ran the breadth and length of the ship’s deck. Approximately 30 other men were detained with the crew of the Jossette, each of them wearing the same white coveralls and chained by one of their ankles to the same cable. Weir and the crew later learned these men were from Latin American countries like Panama and Honduras, and that some had already been on board for several months.

It was then, as the bewildered men sat chained to the deck wondering what the Coast Guard could possibly want with them, that the Coast Guard officers destroyed their fishing boat. On board were all of their fishing gear, and some personal items including a small plastic bucket of clothes that Ferguson had purchased for his two-year-old daughter, France, just before he left home.

The Confidence sailed for about three nights and four days before it reached the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo Bay. For the duration of the journey there, the Coast Guard held the men in grossly inhumane conditions. The men remained chained, the shackles cutting into the their ankles. Their movement was restricted to one spot on the cable — they could only stand, sit, or lie down. The only respite from this agony came when they were unchained to relieve themselves either in a shared metal-bucket or over the side of the ship.

Fearing that their families would think them dead, the men repeatedly begged the Coast Guard to allow them to make a phone call home, or for the Coast Guard to do so on their behalf. But the officers always refused, telling them that it was not permitted under Coast Guard policy.

The sole shelter the Coast Guard provided the men was a plastic tarpaulin that was strung up over them. It provided little protection from the wind, rain, and sun. The men’s skin quickly blistered due to exposure to the constant sun, wind, and salt air. To sleep, each man was given a thin rubber mat and one thin cover, which offered little protection from the ship’s rough metal deck or the biting cold during the early morning hours and late at night.

The psychological torment of captivity made sleeping even more difficult. “It's hard to sleep on that boat,” Patterson said. “Because it's your first time experiencing something like that. Chained by your foot on the deck of a boat. Out in the open. The food wasn't good. You couldn't sleep because some time you get a little food and you're still hungry. So no comfort, so you couldn't sleep. Then some night it's the rain. You'll be there lying down trying to get some sleep. Then comes the rain. Gotta get up. You probably have to sit up there for a while until the rain is gone.”

They were provided with three identical meals a day: a meager ration of cold rice and beans. The only water the Coast Guard gave them to drink was briny and made them nauseous. And to wash off the salt, dirt, and grime that became caked on them, the men were permitted a single cold-water shower in the four days that they were aboard the Confidence.

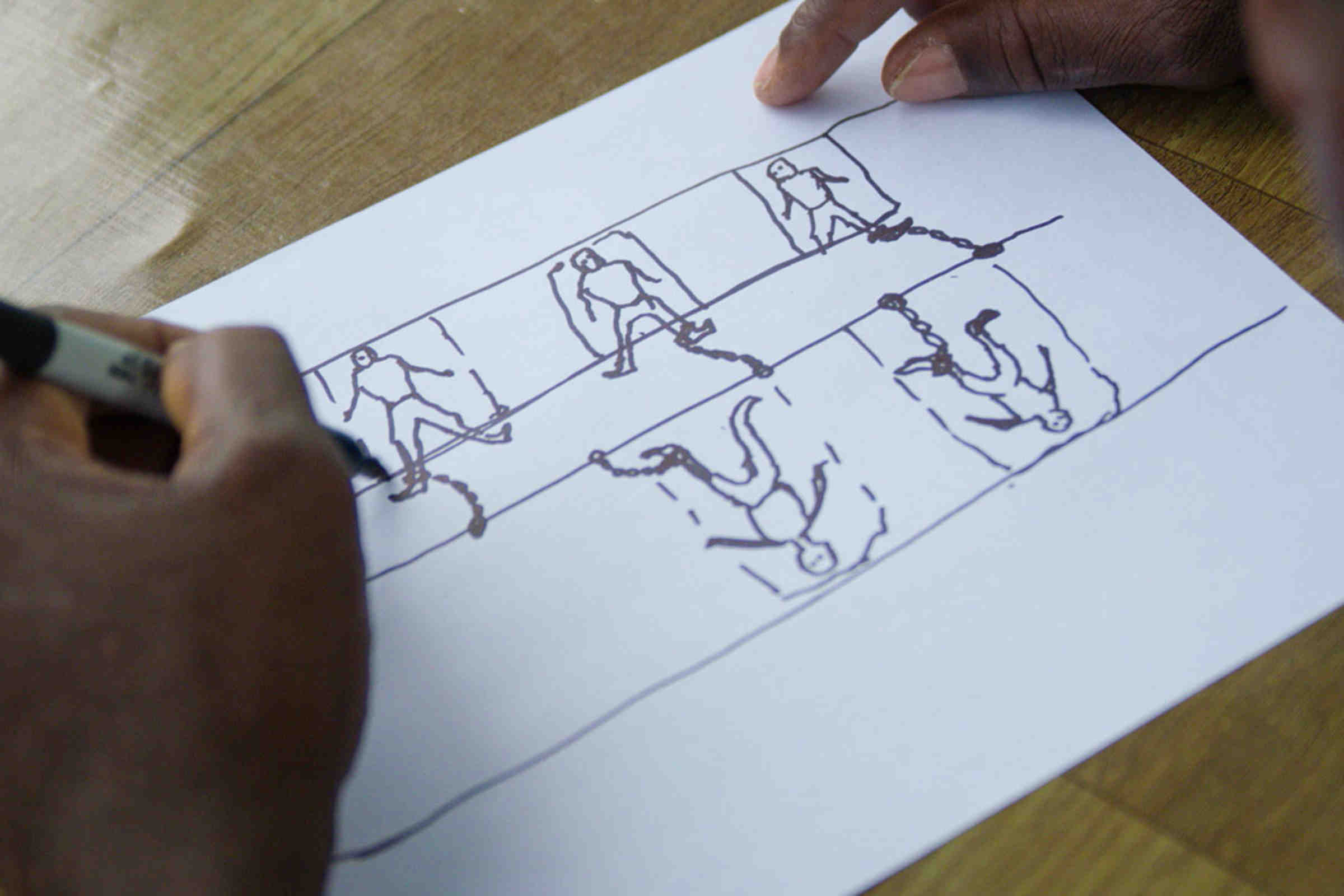

Robert Weir's rendering of his confinement abroad the Confidence.

In all the years the men had spent fishing on the open ocean, they had never experienced anything like the horror they endured on that Coast Guard ship. Because of the substantial risks caused by constant and prolonged exposure to the elements, the men would never spend longer than a day or two on the exposed deck of a small fishing boat such as the Jossette. If they were at sea for any longer stretch, they would overnight on one of the cays where they would be protected from the elements.

After the Confidence docked at Guantanamo Bay, some of the other men on the ship were flown to Miami to be criminally prosecuted. But Weir, Ferguson, Patterson, and Williams were not. Instead Coast Guard officers transferred them to a second Coast Guard ship, and, just like as the Confidence, officers chained them to its deck. The Coast Guard did not say where they would be taken, but the men thought perhaps back to Jamaica. They were sadly mistaken.

After holding the men overnight on the second ship, the Coast Guard set sail for St. Thomas, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico, with the men chained on the exposed deck while Hurricane Maria, a Category 5 hurricane and the deadliest Atlantic hurricane in more than a decade, was churning nearby.

“[The storm] was horrible, it was like hard raining it's all like lightning flashing,” explained Patterson. The wind howled, the ship violently pitched, rolled, and swayed, and waves repeatedly crashed over the deck, drenching the men. Even during the worst of the storm, the Coast Guard refused to allow the men to shelter inside the ship or to provide them with a tarpaulin for shelter. “It was horrible," Patterson said. "We feared for our life." For hours, the men feared that the cables would break and that they would be washed overboard to their deaths.

Compounding their hunger and thirst, each of the men developed ear, nose, throat, chest, and skin infections from their constant exposure to the cold in the early mornings and at night, wind, rain, and seawater. They requested medical treatment for their injuries, but the Coast Guard personnel told them that there was no doctor on board, and their injuries went untreated.

Robert Weir

About three days after leaving Guantanamo Bay, the ship arrived in St. Thomas. It docked in the harbor there for several hours before leaving for Puerto Rico. About three days and three nights later, it docked at a pier in the Port of San Juan for about two nights and days. Despite previously refusing to provide the men with a tarpaulin during the hurricane, before arriving at the port, Coast Guard officers covered the area where they had chained the men with a thick, dark tarpaulin. Whenever one of the men lifted the tarpaulin to look outside, a Coast Guard officer would berate them and quickly pull the tarpaulin down again. The addition of the tarpaulin then was a deliberate and successful attempt to hide the men from onlookers, as the men would otherwise have been visible from the pier.

“It's just like when you're watching a movie when they're like the slave ship. Yeah that's how they treat us, just the same way that you would see the people on the slave ship. Chained up,” Ferguson said. “They feed you whenever they want. They give you anything and you have to just eat it and drink it to save your life.”

Suffering from the conditions of their confinement, including pain from rashes, infections, and other ailments, distraught by the seeming indefinite nature of their secret detention, and tormented by the certainty that their families believed them to be dead, the men had recurring thoughts of killing themselves. Only thoughts of their loved ones waiting for them back home and encouragement from one another to stay strong stopped them from acting on these thoughts.

“It's serious, man. If I tell you you probably wouldn't understand, but…the experience is different, you know,” Patterson said. “You go out there to make a living and these guys pick you up and it's like they torturing you.”

Luther Patterson

This horrific treatment continued on two more ships. Aside from receiving some medical treatment for some of their physical injuries on the third ship, the Coast Guard continued to subject the men to the same squalid conditions. As the men sat chained to the ships’ decks, they had no idea what was going to happen to them. With each transfer, the men became increasingly fearful that the Coast Guard would never take them to land, let alone Jamaica. They thought the Coast Guard officers might hold them indefinitely or, worse still, kill them by throwing them overboard. The cumulative effect of the brutal conditions took a toll on the men, so much so that they began to fear that they would die as a result of them. Their fear increased each time the ship docked and the men were placed on yet another ship.

After over a month of inhumane treatment and complete isolation chained to the open decks of the four coast guard ships, wracked by fear, uncertainty and hopelessness, the men arrived in Miami. They were gaunt and weak, each of them having lost a significant amount of their body weight because of the lack of adequate food and water, sleep deprivation, and other psychological trauma caused by the cruel conditions of their confinement.

“There is no human rights out there,” Patterson said. “They treat you like animals. You are like an animal…chained to the deck on your foot.”

Back in Jamaica, each of the men’s families became increasingly concerned for their safety after they did not return to home, as they had promised on Sept. 15. Some of their family members made inquiries with the Jamaican police and Coast Guard, filing missing person reports on their loved ones’ disappearance. Others made inquiries with local government officials and other fishermen in the area. In desperation, some family members posted on Facebook seeking information on the men’s whereabouts. All of these efforts were to no avail.

“Well that whole month, I think I never sleep one minute. It's a horrible feeling. I think the worst feeling I ever had,” Keisha, Ferguson’s girlfriend, said.

As the weeks went by with no word from the men, some family members considered them lost at sea and mourned their deaths. Weir’s family began to give away his clothes and other personal possessions, and neighbors began taking his livestock, including goats, pigs, and chickens. Ferguson’s family gave away his vehicle, as did Patterson’s, together with his herd of 15 goats. And Williams’ family gave away many of his clothes and personal possessions and began to make arrangements for his funeral.

David Williams and his partner Angelina Lewis.

On Oct. 16, 2017, after 32 days of inhumane and incommunicado detention, the Coast Guard finally delivered the men to Miami and to the custody of the Drug Enforcement Administration. On Oct. 18, the United States charged the men with trafficking marijuana. The men pleaded not guilty to these charges and were detained pending trial. Shortly afterward, the men were each allowed their first phone call home to their families — the first time in over a month. “I was all over in tears,” Williams’ girlfriend Anne said when she first heard David’s voice. “And then he said ‘okay don't cry, I'm okay, I'm not dying.’”

On Dec. 13, the United States charged the men, not with any drug-related charge, but with providing “false information” to the Coast Guard during the Coast Guard’s boarding of the Jossette about the Jossette’s destination. In January 2018, pursuant to written plea agreements, the men pleaded guilty to this charge. Specifically, the plea agreements stipulated that they claimed their destination was the waters near the coast of Jamaica where they intended to fish when in fact they were headed for Haiti. A federal court sentenced them each to 10 months’ imprisonment. But the men had not lied to the Coast Guard officers on the Jossette. They pleaded guilty because they were told that it was the quickest and surest way to get back to their homes and families in Jamaica and to put an end to their nightmare.

Although the Coast Guard claims that it initially apprehended the men because it suspected that they were trafficking marijuana, at their sentencing hearing the assistant U.S. attorney prosecuting their case acknowledged that it would, in fact, have taken “a miracle” to prove to a jury that there were ever any marijuana on the men’s boat, one that he “could not have pulled off.”

On Aug. 30, 2018, after serving their sentences and spending a further two months in federal immigration detention due to a delay caused by the U.S. government, officials returned the men to Jamaica, almost a year to the day since they had left Half Moon Bay.

Since their return to their homes and families in Jamaica, the men continue to be traumatized by their 32 days of detention by the Coast Guard. Ferguson suffers persistent flashbacks to his time on the Coast Guard ships and in particular, to the time he saw the Coast Guard officers destroy his boat. Ferguson remains so traumatized that he has not gone fishing since his return to Jamaica. Patterson still feels the steely grip of the chain on his ankles, and at times he cannot sleep thinking about how the Coast Guard abused him. The experience also had a profound impact on their families.

“She [is] traumatized,” Ferguson said of his 10-year-old daughter. “Your kids hear their father [is] dead. It affect them, man.”

Patrick Ferguson

The men also returned to financial ruin. The destruction of his boat and fishing gear and the loss of fishing traps resulted in a huge loss of income for Ferguson. He now has to rely on his extended family to support him and his family.

Since Patterson’s return to Jamaica, he has struggled financially with the loss of his car and livestock while he was detained. He has yet to find a regular spot on a fishing crew because most crews require travel far offshore, which Patterson refuses to do because of his fear that the Coast Guard will seize, detain, and mistreat him again.

“I gotta start all over. Pick my life up, you know, fix the pieces all over again,” Patterson said.

The Coast Guard’s inhumane treatment and detention of the men is not an aberration. It is part of a well-documented pattern and practice that ramped up in 2012 as part of the United States “war on drugs.” The Coast Guard has taken thousands of men from their boats and held them for weeks or months in their “floating Guantanamos,” as a former Coast Guard lawyer characterized them to a reporter writing in The New York Times Magazine in 2017.

The Coast Guard policies that resulted in these abuses remain in effect and other foreign nationals continue to be subject to it.

The American Civil Liberties Union, the ACLU of the District of Columbia, and the New York-based law firm, Stroock & Stroock & Lavan, filed a lawsuit against the United States and the head of the Coast Guard seeking damages on behalf of Weir, Ferguson, Patterson, and Williams for the Coast Guard’s unlawful destruction of their boat and other property and for the trauma the men suffered as a consequence of their detention. The men are also seeking to end the Coast Guard’s horrific practice.

“Because I wasn't involved in [anything] that's wrong,” Williams said when asked why he wanted to join this lawsuit. “I was going to do something to help myself and help my family…it was fishing. I just had lost my way. And so with that type of treatment we all [got], I would like the American government to do something about it.”

Weir v. U.S.

The American Civil Liberties Union filed a federal lawsuit in June 2019 against the United States and the head of the U.S. Coast Guard on behalf of...

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

ACLU Sues Coast Guard for Kidnapping, Abusive Treatment of Jamaican Fishermen

Men Suffered Burns, Trauma, and Financial Ruin Due to Month-Long Forced Detention At Sea

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

I’ve Been to Guantanamo. It’s No Place for Kids.

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

Out of the Darkness

How two psychologists teamed up with the CIA to devise a torture program and experiment on human beings.

Source: American Civil Liberties Union