W.E.B. Du Bois’s Historic U.N. Petition Continues to Inspire Human Rights Advocacy

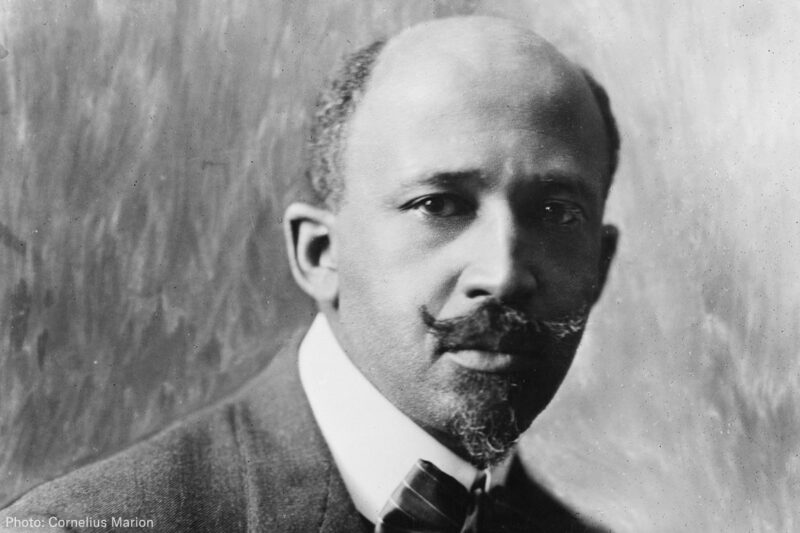

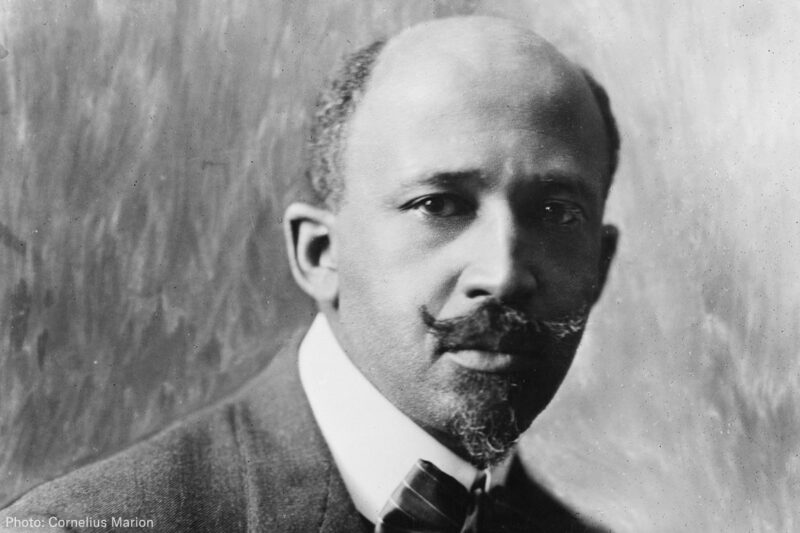

Seventy years ago this week, the oldest civil rights organization in the world, the NAACP, submitted a petition to the newly established United Nations demanding accountability for human rights violations against African Americans in the United States. The 96-page petition was written over the course of a year under the editorial supervision of W.E.B. Du Bois. Its six chapters, each written by a leading expert, cover topics ranging from slavery and Jim Crow to voting rights, criminal justice, education, employment and access to health care – areas in which discrimination remains deeply rooted to this day.

In view of this legacy, it will be interesting to see the Trump administration’s report on America’s compliance with the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which is expected by Nov. 20. Earlier this week, the ACLU joined the NAACP, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law and the U.S. Human Rights Network in calling on the administration to submit a comprehensive report that thoroughly reviews both progress and setbacks in implementing the anti-racial discrimination treaty on federal, state and local levels.

In August, the ACLU submitted a letter to the administration expressing serious concerns about the lack of progress in implementing key recommendations issued by the U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in 2014, especially in the areas of education, criminal justice, voting rights and immigration, and in the rollback of civil rights enforcement across federal departments.

Du Bois’s petition to the U.N. is considered one of the first organized efforts to focus on human rights issues in the United States. At that time, just a few years after the United Nations was established and at the start of the Cold War, the United States was setting out to create a new world order, assert American moral leadership in human rights and to counter the influence of the Soviet Union.

But it soon became clear that the United States was not living up the human rights standards it was advocating for the rest of the world. Fearing that the double standard would be exposed, President Truman’s State Department worked relentlessly to undermine the emerging human rights infrastructure at the U.N. In internal documents, the State Department admitted that it was worried about the creation of an international forum where it would be too tempting to raise the “Negro problem.”

Du Bois and other civil rights leaders took the commitments the United States demanded of other countries and turned them on the U.S., asking how Americans were protecting human rights at home and pointing out the hypocrisy when millions of Black people in the U.S. were subject to racial segregation and denial of the most basic rights.

Du Bois’s petition was published in 1947, a year before the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and almost 20 years before the drafting of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. In fact, the U.N. Commission on Human Rights had only been established in February 1946 and led by former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

Du Bois was inspired to write his appeal by the National Negro Congress, which had submitted its own petition in 1946. That shorter petition was written by the historian Herbert Aptheker and outlined the economic, political and social oppression facing Black America at the time. The U.N. replied to that petition by emphasizing its lack of authority to intervene in domestic matters – not uncommon response at the time.

According to the historian Carol Anderson, who wrote about Du Bois’s petition in her remarkable book Eyes Off the Prize: The United Nations and the African American Struggle for Human Rights, Du Bois contacted each U.N. delegation as well as the U.N. Secretary General Trygve Lie to ask for their support to bring the petition before the U.N. General Assembly. The U.S. State Department was unequivocally hostile to his efforts — when Du Bois attempted to enlist the help of Eleanor Roosevelt, who was a member of the American delegation and had joined the NAACP Board in 1945, she was mostly unresponsive, fearing the petition would give the Soviet Union an opportunity to criticize the United States. She later submitted her resignation from the NAACP Board but eventually agreed to stay on.

After extensive media coverage, John Humphrey, the Director of the U.N. Division for Human Rights, agreed to receive the petition. Both the State Department and the United Nations balked at the NAACP’s request to turn the presentation into a media event. Instead, it was limited to a small meeting with about a dozen representatives from the NAACP. Eleanor Roosevelt, notably, turned down the NAACP’s invitation to attend, claiming that as a member of the U.S. delegation she was not in a position to support such a petition.

At the presentation on October 23, 1947, Walter White of the NAACP described how “injustice against black men in America” had repercussions “for the “brown men of India, yellow men of China, and black men of Africa.” Du Bois also placed the petition in the global context, claiming that saving democracy abroad required saving it at home. He demanded a world hearing to persuade the U.S. “to be just to its own people.” Humphrey listened patiently to the presentation, and afterward responded that he had to keep the petition confidential, as that Human Rights Commission had “no power to take any action… concerning human rights.”

While the petition did not lead to concrete results at the U.N., it did focus domestic and international attention on racial discrimination in the U.S. A senator from Kansas introduced the petition into the Congressional record and Attorney General Tom C. Clark claimed that he “was humiliated… to realize that in our America there could be the slightest foundation for such a petition.” President Truman continued to push for civil rights, addressing Congress in February 1948 and arguing that American’s position in the world, made civil rights “especially urgent.”

The 1947 petition continued to serve as an overarching framework for efforts by Black leadership to lobby the United Nations. In December 1951, the Civil Rights Congress published a petition entitled “We Charge Genocide: The Historic Petition to the United Nations for Relief From a Crime of The United States Government Against the Negro People.” This document, using social science data, outlined instances of mob violence and police terror over the previous half-decade. As with the NAACP petition, the State Department did all in its power to minimize its impact. But despite those efforts, the petition received widespread media coverage and helped bring the issue of lynching and state violence to the world stage.

Seventy years on, we continue to draw inspiration from DuBois’s broad vision and bold actions to hold the United States accountable to the rest of the world for its failure to end structural racism and racial discrimination. Today, we are especially concerned about the rise of white supremacy, racism, and xenophobia and deeply troubled by a federal government that has shown an intention to roll back civil rights enforcement and ultimately widen existing racial disparities. The world is – and will continue to be – watching, and America should not rest until DuBois’s vision for racial equality is fully realized.