This piece originally ran at The Huffington Post.

"Let's go home."

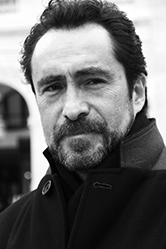

These are the closing words of A Better Life, which my character, the undocumented gardener Carlos Galindo, says as he prepares to walk into the desert and begin his journey back to America and his teenage son after being deported.

Like Carlos Galindo, I was once an undocumented worker.

My story, however, bears no resemblance to his, or the approximately 12 million undocumented immigrants currently in the United States like him. I came to America for adventure and to learn English with no work visa. When my tourist visa ran out, I continued to work as a waiter in New York, and if I was discovered, I would return to my life in Mexico. That never happened because I eventually became a permanent resident and later on an American citizen, like 3 million other undocumented workers, after Congress passed and President Ronald Reagan signed the Immigration Reform Control Act of 1986.

I was one of the lucky ones.

For the majority of the undocumented immigrants currently living inside the United States, deportation isn't an inconvenience. It is a terrifying, traumatic experience that rips people away from their homes, their communities, and, more importantly, the ones they love. Playing Carlos Galindo was my way to wear their skins for a while. As the character, I felt the anxiety of compulsively wondering whether that light I just drove through was yellow or red, the panic whenever a police officer gazed at me for a few seconds too many, and the dread that filled me when I left home for the day, fearing it could be the last time I set eyes upon it.

For Carlos Galindo and everyone like him, that is how they live their lives, every day. They fear that being in the wrong place at the wrong time could lead to exile, and it's a terrible burden to bear.

During the 2008 campaign, Senator Barack Obama seemed to understand their pain and promised to fix our broken immigration system. He promised to enact comprehensive immigration reform and create a pathway to citizenship for the millions of hardworking people who labor for little money at often thankless jobs to make their children's lives -- and for that matter our lives -- a little bit easier. He pledged to no longer separate children from their parents. Today 4 million childrencall an undocumented immigrant mom or dad. Children who hug their parents extra tight before they leave for work for fear they'll never see them again.

Latinos, like me, rewarded Obama with our vote. In 2008: because he warmed our hearts. In 2012: because we believed his second term would free him to get immigration reform done, regardless of Republican obstructionism.

But the hope he inspired has spiraled into hopelessness.

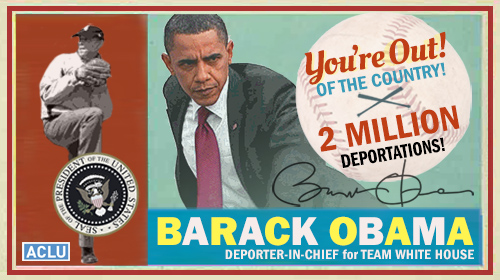

Since President Obama assumed office, he has deported more than 2 million human beings -- husbands and wives, mothers and fathers, brothers and sisters. In March, the president looked as if he couldn't stomach his deportation record any longer, ordering his new head of homeland security to review how the White House could make the nation's deportation policies more "humane."

Maybe the deporter-in-chief would be the reformer-in-chief after all.

But in late May, President Obama delayed the review in the belief he could get House Republicans to come to the table and agree on immigration reform before Congress recesses for August. By doing so, the pace of the deportation machine will keep churning, grinding up thousands and thousands of more lives for a gamble whose odds of success are about as long as the fences erected across the Southwest border. This will only reinforce the schizophrenic "We don't want them here, but we need them here" mindset that exploits undocumented workers' labor without any sense of fairness or gratitude for their contributions to our prosperity.

I wish I could set up a screening of A Better Life for the president. During its many screenings across the country, the lights come up, and you can feel the prejudice purged from the room and replaced with empathy. More often than not, I hear something like this, "It's the first time I noticed those trucks are gardening trucks and that there are human beings inside who live in fear." Then there are the responses of my friends after watching the film, "You know I see those trucks everywhere now, and they used to be invisible."

I want President Obama to have the same epiphany, so sometime soon when someone like Carlos Galindo utters the words, "Let's go home," he isn't on the outside looking in.

Learn more about immigration deportation and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.