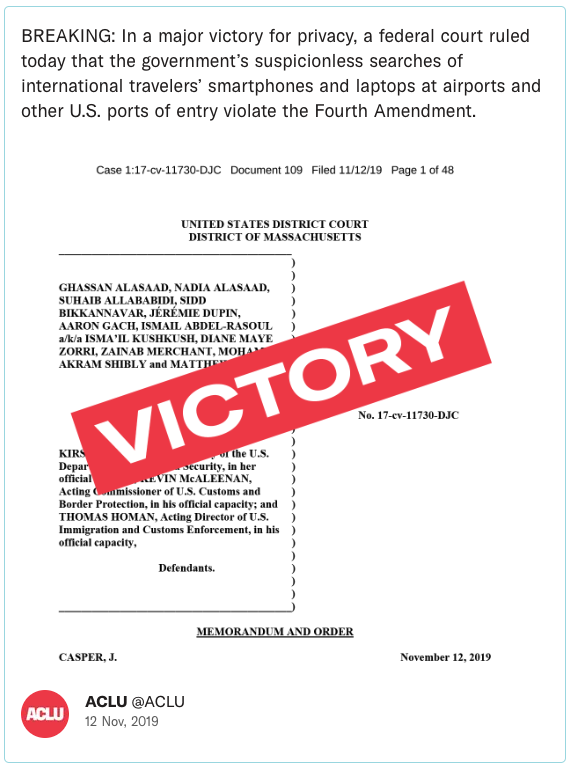

Federal Court Rules That Border Officers Can’t Arbitrarily Search Our Electronic Devices

In a major victory for privacy rights, a federal court has held that the federal government’s suspicionless searches of smartphones, laptops, and other electronic devices at airports or other U.S. ports of entry are unconstitutional. The ruling in our case is a recognition that the Constitution protects us even at the border, and that traveling to or from the United States doesn’t mean we give the government unfettered access to the trove of personal information on our mobile devices.

In recent years, as the number of devices searched at the border has quadrupled, international travelers returning to the United States have increasingly reported cases of invasive searches. For instance, a border officer searched our client Zainab Merchant’s phone, despite her informing the officer that it contained privileged attorney-client communications. And recently, at Boston Logan Airport, an immigration officer reportedly searched an incoming Harvard freshman’s cell phone and laptop, reprimanded the student for his friends’ social media posts expressing views critical of the U.S. government, and denied the student entry into the country following the search.

These cases aren’t unique. Documents and testimony we and the Electronic Frontier Foundation obtained as part of our lawsuit challenging the searches revealed that the government has been using the border as a digital dragnet. CBP and ICE claim sweeping authority to search our devices for purposes far removed from customs enforcement, such as finding information about someone other than the device’s owner.

We Got U.S. Border Officials to Testify Under Oath. Here’s What We Found Out.

In September 2017 we, along with the Electronic Frontier Foundation, sued the federal government for its warrantless and suspicionless searches

Source: American Civil Liberties Union

The court’s order makes clear that these fishing expeditions violate the Fourth Amendment. The government must now demonstrate reasonable suspicion that a device contains illegal contraband. That’s a far more rigorous standard than the status quo, under which officials claim they can rummage through the personal information on our devices at whim and with no suspicion at all.

It’s difficult to overstate how much personal information our electronic devices contain, and how revealing searches of those devices can be. Our smartphones are unlike any other item officers encounter at the border — they likely contain years of emails, messages, videos, photos, location data, browsing history, and medical and financial data. A search of our clients’ devices revealed photos of themselves without head coverings worn in public for religious reasons. Others had information on their devices related to their work as journalists.

The bottom line is that for most of us, our phones contain far more information than could be found during a thorough search of our homes.

The court recognized these critical privacy issues in its ruling. It stated that travelers’ privacy interests in their devices are “vast” and that “the potential level of intrusion from a search of a person’s electronic devices simply has no easy comparison to non-digital searches.” In other words: Digital is different. While the government can search luggage and other physical items at the border without individualized suspicion, it can’t use that authority to rifle through the universe of personal data on our electronic devices.

In reaching that conclusion, the court relied on recent Supreme Court decisions that make clear that older rules under the Fourth Amendment cannot be mechanically extended to justify new kinds of invasive digital-age searches. As the Supreme Court put it, equating searches of physical items and digital devices “is like saying a ride on horseback is materially indistinguishable from a flight to the moon.... Modern cell phones, as a category, implicate privacy concerns far beyond those implicated by the search of a cigarette pack, a wallet, or a purse.” The federal court explained this week that the magnitude of the privacy harms is no less great in the context of border searches, requiring stronger Fourth Amendment protections against searches of electronic devices at the border as well.

The court has not yet issued an order regarding how the government should implement the ruling.

Significant work remains to be done to ensure that government officials respect our constitutional rights in the digital realm and at the border. The court’s ruling is a big step in the right direction.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.