The Incarceration of Japanese Americans in World War II Does Not Provide a Legal Cover for a Muslim Registry

This article was originally published by the Los Angeles Times.

Carl Higbie, a prominent supporter of Donald Trump, said recently that the mass internment of Japanese Americans during World War II was a “precedent” for the president-elect’s plans to create a registry for immigrants from Muslim countries. He said the plan would be legal, that it would “hold constitutional muster.”

That claim betrays a misreading of history. It rests on a wartime Supreme Court decision that was based on falsehoods and suppressed evidence, a decision that is regarded as a stain on American jurisprudence.

In February 1942, shortly after the Japanese attack on the United States at Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. About 120,000 Japanese Americans — two-thirds of them native-born U.S. citizens — had to register and report to assembly centers. They had just days to divest themselves of all they owned — their homes, farms and businesses. With just what they could carry, they were shipped off to federally run “internment camps,” imprisoned behind barbed wire and watched by armed guards.

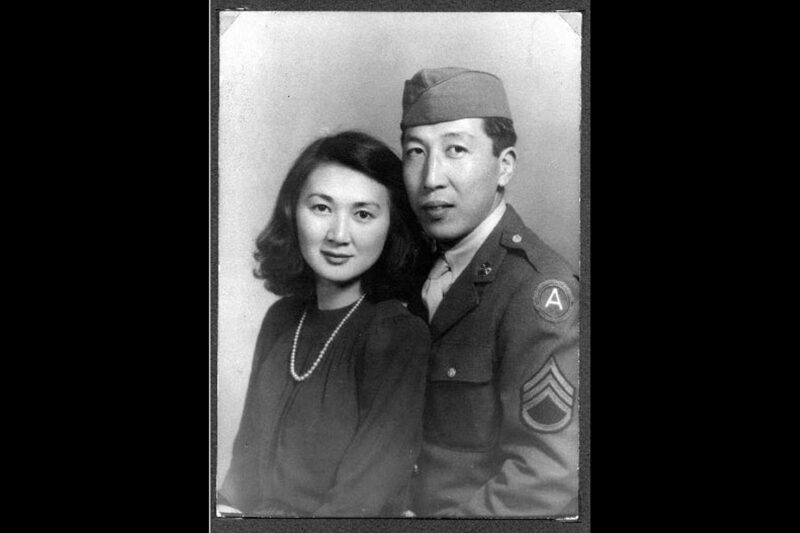

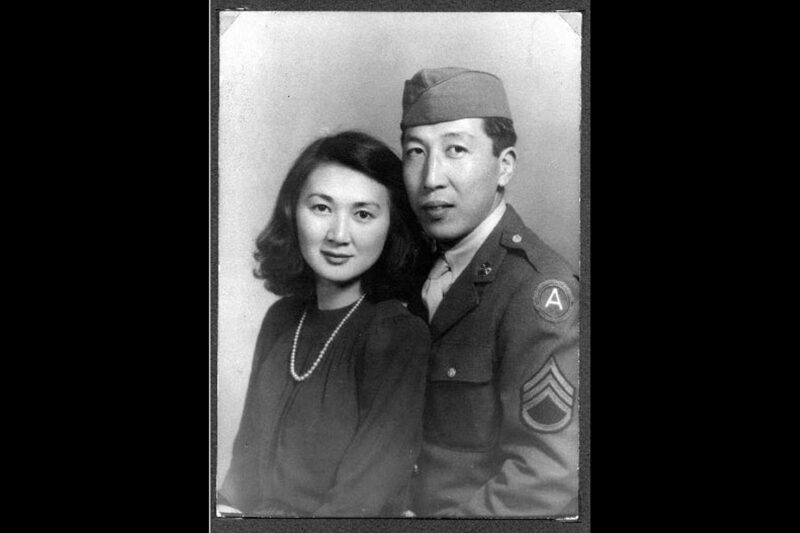

My grandmother, Bette Takei, was one of them. She was incarcerated in Colorado, while her husband, my grandfather, Kuichi Takei, fought in an artillery unit of the United States Army in Europe. Bette was from a small town in the Sacramento River Delta; Kuichi was from Santa Cruz.

In the Bay Area, 23-year-old Fred T. Korematsu quietly defied the February 1942 order. He was picked up, arrested and convicted, and then he too was imprisoned. The ACLU of Northern California represented him before the U.S. Supreme Court, challenging the policy of roundups and incarceration. In 1944 — after D-day but before the war was over — Korematsu lost.

It was not a unanimous decision. In one dissent, Justice Frank Murphy wrote, “Racial discrimination in any form and in any degree has no justifiable part whatever in our democratic way of life.” Justice Robert Jackson wrote that the court should not affirm the military order because “the principle then lies about like a loaded weapon, ready for the hand of any authority that can bring forward a plausible claim of an urgent need.”

Decades later, Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga, a researcher for a congressional commission appointed to consider legislative redress for victims of the wartime incarceration, who had herself been rounded up as a teenager, found a curious document in the National Archives.

In Korematsu’s Supreme Court case, government lawyers had submitted a report by Lt. Gen. General John L. DeWitt, and quoted from it in their oral arguments to justify the executive order. They won in large part because of this report, which claimed that the imprisonment of Japanese Americans was a military necessity because there was no time for government officials to determine who was loyal and who might be a security threat.

DeWitt’s racist views were widely known: “A Jap’s a Jap,” he said publicly. “It makes no difference whether he is an American citizen or not.” But his report offered a plausible justification for Roosevelt’s policy, and it carried the day.

What Herzig-Yoshinaga found was an earlier draft of DeWitt’s report, which said that anyone of Japanese ancestry in the U.S. had to be rounded up simply because Japanese racial characteristics made it impossible to distinguish “the sheep from the goats” — no matter how much time was available.

Had this original report been submitted to the court, it’s likely the justices would have realized that racism, not time pressure, was the true motivation for the indiscriminate roundup. Instead, almost all copies of the original were destroyed. It was purposefully kept out of the record, along with intelligence reports showing that Japanese Americans posed no credible threat to the U.S.

In the early 1980s, the judiciary, in effect, apologized. Korematsu and two other Japanese Americans who had lost wartime challenges against their incarceration, petitioned to overturn their decades-old criminal convictions. They succeeded using a legal procedure called coram nobis, the equivalent of the judiciary admitting a serious mistake.

The coram nobis cases never reached the Supreme Court because the plaintiffs won at lower levels. So far, the high court has not heard a case that called on it to overturn the original Korematsu decision. Nonetheless, the ruling is as close to completely repudiated as it could be without having been formally overruled.

Federal District Court Judge Marilyn Hall Patel wrote, presciently, in her 1984 opinion overturning Korematsu’s conviction: “In times of international hostility and antagonism, our institutions, legislative, executive and judicial, must be prepared to exercise their authority to protect all citizens from the petty fears and prejudices that are so easily aroused.”

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988, signed into law by President Reagan, provided reparations of $20,000 to each Japanese American camp survivor. The legislation admitted that Executive Order 9066 was based on “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.” Reagan called the incarceration “a great injustice” and apologized on behalf of all Americans. More than $1.6 billion in reparations was disbursed.

Despite that apology, our leaders have become increasingly bold in unlearning this lesson. Korematsu himself returned to the Supreme Court in 2004 to file a brief challenging the indefinite detention of prisoners at Guantanamo Bay. Now, the racist underpinnings of the World War II incarceration are being used to push for a Muslim registry.

My family framed the apology letter my grandparents got from the government. It is signed by President George H.W. Bush and it hangs on the wall of the home I grew up in. “We can never fully right the wrongs of the past,” it says.

When my grandfather died in November 2014, he believed the extreme prejudice he and my grandmother faced had ended. We should remember the wrongs they suffered, not revive them.