Reuniting a Mother and Child Torn Apart by ICE

Last week I visited our client Ms. L, a Congolese mother whose 7-year-old daughter was taken away from her by Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials shortly after she entered the United States last year.

She was now at a shelter for formerly detained immigrants in Chicago, awaiting reunification with her daughter, whom she had not seen in over four months.

Ms. L, whose name we are withholding to preserve her privacy, showed me several photographs of her beautiful little girl. In one, the little girl was sitting on a staircase next to a woman, both of them grinning into the camera. I asked who the woman was, and Ms. L looked at me with surprise.

“It’s me,” she said.

The smiling woman in the photo didn’t look anything like the distraught, gaunt woman with the empty stare whom I first met at a San Diego detention facility in February. It was taken a few months ago, before ICE took her daughter away. Because of her distress, Ms. L hadn’t slept or eaten well in weeks.

Ms. L and daughter fled the Democratic Republic of Congo in grave danger, and when they reached the United States on Nov.1, they immediately asked for political asylum.

They were taken into custody together. But four days later, Ms. L said ICE officials handcuffed her, put a restraint around her waist and ankles and took her daughter away. Ms. L was locked up in the Otay Mesa Detention Center near San Diego. Her daughter was taken to Chicago and put in a facility for “unaccompanied” immigrant minors.

The two would still be on opposite sides of the country if we hadn’t filed a lawsuit on Feb. 26. The Department of Homeland Security, which oversees ICE, announced in December that it was considering separating children from their parents when they came to the United States to deter others from coming. Evidence suggests it had already begun doing so.

According to organizations that monitor detention facilities and provide services to asylum-seekers, there are hundreds of other children who have been separated from their parents. On March 9, the ACLU filed a motion expanding our lawsuit on behalf of Ms. L. into a nationwide class action suit on behalf of the hundreds of other unnamed families who have been torn apart.

Ms. L and her daughter were given no explanation for the separation, had no lawyers and knew no one in the United States. Days after our lawsuit, and the media coverage and outrage that followed, the government abruptly released Ms. L.

Concerned citizens across the country began contacting the ACLU asking what they could do to help. Among them was a couple in San Marcos, a suburb of San Diego, who heard about Ms. L and her daughter on NPR and offered to take her in. The couple had no connection to the Congo. She is a retired nurse, and her husband had been a banker.

Ms. L speaks Lingala and a little bit of Spanish. This couple spoke neither, but pantomimed their way through five days together.

Ms. L and her daughter are Catholic and a church had helped them flee the Congo. So, on the evening of March 13, the night before she was to fly to Chicago, where she would eventually be reunited with her daughter, the couple and Ms. L sat down to dinner, held hands and said grace.

The government agency in charge of “unaccompanied” immigrant minors, the Office of Refugee Resettlement, had said it would take at least a week to release the daughter.

“I thank God if I can be with her in a week,” Ms. L said.

The next morning, Ms. L boarded a flight for Chicago. Once there, she went to a shelter for immigrants newly released from immigration detention where the staff welcomed her with open arms. They introduced her to a couple of other residents — there are 12 living there – and showed Ms. L her room. One of the shelter volunteers had left a basket with a card and a stuffed animal for Ms. L’s daughter. The staff asked her if there was anything she needed. She said simply that she needed her daughter.

On Thursday, in Chicago’s Federal Plaza, people gathered to protest ICE’s practice of separating families. It was during the protest that I received a message saying that Ms. L would likely be reunited with her daughter the following day, Friday, March 16.

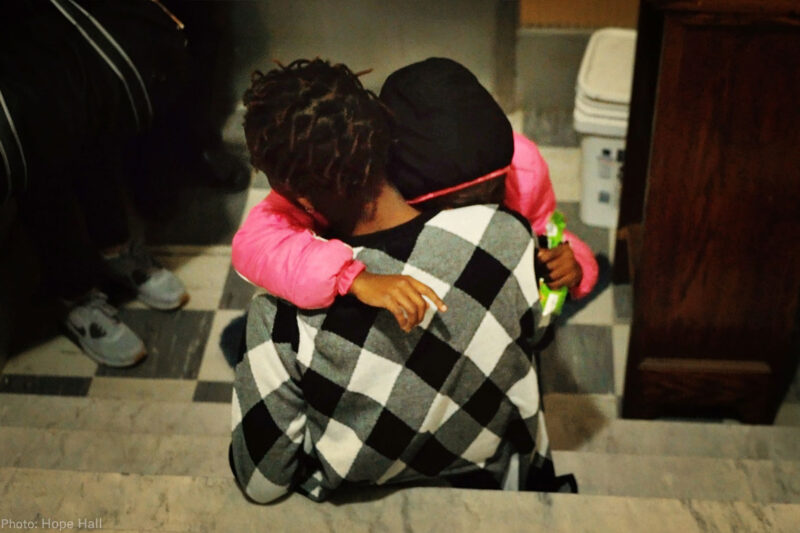

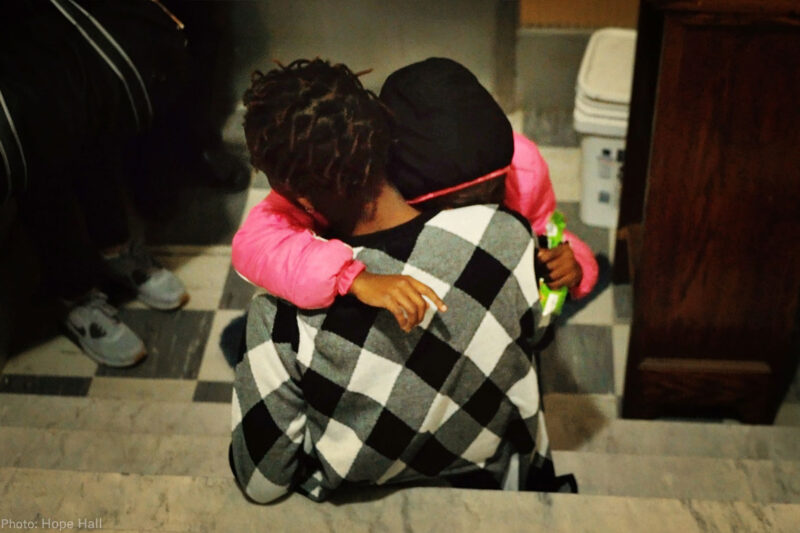

At 9 p.m., on March 16, Ms. L’s daughter walked through the door. Mother and daughter fell into each other’s arms and lay on the floor sobbing. Ms. L said something to her daughter in Lingala and pointed at me and the daughter came and hugged me. It is a moment I will never forget.

We were able to reunite Ms. L and her daughter, but there are hundreds of other children in the United States who are still separated from their parents in immigration detention. Our hope is that we can reunite them all and that ICE will stop the practice so no other family must endure what Ms. L and her daughter went through.