The ‘ICE Kids’

This piece was published in partnership with The Nation.

On a cold, rainy night last November, Bastian Rodriguez spent the first hours of his 18th birthday inside an Immigration and Customs Enforcement van. Rodriguez was aging out of the Cowlitz County Youth Services Center, a juvenile jail in Longview, Wash., and was on his way to the Northwest ICE Processing Center, a privately run immigration detention facility for adults in Tacoma. He had already spent more than two years in ICE custody.

“These adult people are going to beat my ass,” he told me he worried as the van wound its way toward Tacoma. “I know it’s your birthday, so I’m going to be cool with you,” the guard driving the van told Rodriguez, making a pit stop at McDonalds to buy him a Big Mac. As they continued, Rodriguez sat in the back eating, afraid of what would happen to him in the big prison filled with people much older than him.

Until recently, Rodriguez’s long detention under ICE control had been rare for someone his age. For the most part, the agency doesn’t have the authority to hold children for more than a few days. The 1997 Flores settlement agreement requires that minors be released from immigration detention “without unnecessary delay” and turned over to family members or sponsors. But the settlement has an exemption for minors with a criminal record or who have been accused of committing a “chargeable offense.”

Typically, these minors are held in a secure facility run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement, an agency whose mandate prioritizes care rather than enforcement, where they have access to an attorney and are regularly seen by child psychologists.

But Rodriguez was one of a still-unknown number of teenagers who have instead been sent by ICE to juvenile jails that are often thousands of miles away from their families, and where there are no safeguards in place to guarantee that they were represented in court for the months — and in some cases, years — of their detention. Advocates say the practice is illegal and violates the Flores settlement.

“It’s like a black hole. It’s not family separation or minors picked up at the border — it’s a different, weird situation,” said Samantha Ratcliffe, a Portland, Ore.–based immigration attorney who represented a number of the teenagers. “But it’s just horrifying, and nobody really knows it’s happening.”

ICE says that it holds minors rather than transferring them to ORR custody in “rare circumstances” because they have been “deemed to pose a significant threat to public safety.” But immigration advocates say that the agency has blocked the release of details about their cases that could back up that claim, and point out that some of the teenagers held in facilities like Cowlitz were never convicted of a crime.

“It doesn’t seem like there’s consistency in what the kids’ criminal histories look like,” said Enoka Herat, a police practices and immigration counsel at the ACLU of Washington. “To us it seems totally arbitrary.”

“The kids who were detained under this contract have sort of fallen through the cracks of ICE’s system.”

In early February, under pressure from church groups, local activists, and Washington’s attorney general, a panel of local judges ordered an end to the contract between ICE and Cowlitz County, which had been receiving $170 a day per teenager from the agency since 2011. In their decision the judges said that the long periods the young immigrants had spent there were “not suited for our short-term facility.”

But shortly after the termination of ICE’s contract to hold juveniles at Cowlitz, advocates discovered that the agency had signed a new one, this time with municipal authorities in Winchester, Va. At present, ICE says that it is holding one of the teenagers who was incarcerated with Rodriguez in Cowlitz.

And while Cowlitz’s agreement to incarcerate teenagers on ICE’s behalf ended in March, Rodriguez’s ordeal did not.

“The kids who were detained under this contract have sort of fallen through the cracks of ICE’s system,” said Herat.

A FOIA REQUEST OPENS A SECRET DOOR

In 2018, Angelina Godoy, director of the University of Washington’s Center for Human Rights, was poring over a spreadsheet she’d obtained through a FOIA request from ICE when she noticed something strange. The sheet contained data from nearly 1,700 ICE detention facilities. Three of them, she saw, had been holding minors for periods longer than 72 hours.

Godoy began to look more closely at the facilities, all three of which were juvenile jails whose primary purpose was to house nonimmigrant minors who’d been convicted of crimes. One was in Pennsylvania, another in Oregon, and the third in Cowlitz County, a mountainous part of Washington state about an hour north of Portland. She and her colleagues at UW wanted to know more about who was being held there, so they used public records laws to request information about the agreements the three detention centers had with ICE and the number of immigrant minors jailed in them.

Abraxas Academy in Pennsylvania was privately operated and its administrators declined UW’s request, but Cowlitz and NORCOR, the detention center in Oregon, sent Godoy copies of the contracts they’d signed with ICE.

“The more I scraped the surface and gathered information, the more I was like, ‘Oh my god, how is this happening?’” she said.

All three facilities had agreed to detain minors for ICE alongside their existing population of sentenced juveniles in exchange for federal payments. Those young immigrants — technically in ICE custody — weren’t serving criminal sentences, but were instead being held for violations of civil immigration law while they fought the government’s efforts to deport them.

Cowlitz’s contract had been signed in 2011, with the county agreeing to jail minors who had been classified as “List 1” by ICE — those the agency considered exempt from the Flores settlement’s stricter requirements. Godoy wanted to know who these kids were and why they were being sent to a juvenile jail instead of ORR facilities.

Cowlitz County partially acquiesced to Godoy’s request, giving her incomplete data that indicated ICE had transferred 15 minors to the facility between 2013 and 2018. Some had been held for long periods — hundreds of days at a time in some cases, far longer than the average three-week stay for locals sent to Cowlitz by Washington’s juvenile justice system.

But when Godoy asked for more detailed information about their cases and why they were being held at Cowlitz, ICE stepped in and told county administrators not to provide it.

“They consulted with ICE about releasing information to us under the Washington State Public Records Act, and ICE told them under no circumstances could they release that information to us,” she explained.

Godoy was livid. By blocking Cowlitz from providing UW with data, ICE was violating Washington’s public records laws. But ICE wouldn’t budge. In fact, the agency sued Godoy and the university in state court to prevent her request for redacted files about them from moving any further.

“They were essentially doing an information blackout on the whole facility and rendering it a kind of black site,” said Godoy.

With ICE fending off their requests, Godoy and other researchers began canvassing immigration attorneys in the region, including Samantha Ratcliffe, to see if they knew anything about the minors detained at Cowlitz or NORCOR.

Ratcliffe and her colleagues, as it turned out, had discovered the kids that ICE held at Cowlitz by chance. Some of her colleagues who represented minors in ORR custody had observed mysterious teenagers appearing on the juvenile docket in Portland’s immigration court, but they didn’t know who was holding them and where. They suggested that Ratcliffe and her colleagues look into it.

“That was how we started finding out about them,” she told me. “And we started taking them on because these kids didn’t have representation. No one was funded specifically to serve them.”

In late 2018 Ratcliffe and other immigration attorneys she worked with began taking their cases.

The children locked up at Cowlitz were typically between the ages of 15 to 17. Most had prior juvenile records and were fighting to stay in the United States. They weren’t recent arrivals. They’d been arrested in what ICE calls “the interior” rather than at the border, and most had parents and other close family members in the US, often on the other side of the country.

“Most of these kids were not local,” said Ratcliffe. “They came from the East Coast, some from Southwest Texas or Oklahoma. Obviously, their parents couldn’t be there to visit because they’re too far, so it was just phone calls.”

There wasn’t any one profile that fit all of the teenagers. Some had served time for assault charges — mainly fistfights in high school or other altercations with their peers — or had been arrested for offenses like theft or making threatening comments. But others had never been convicted of any crime. In some cases, they’d just been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

“There was actually one kid who was picked up by ICE at his home who didn’t even have a criminal charge, they were looking for someone else,” said Ratcliffe. “They decided he was dangerous because he had a kitchen knife in his closet, and took him into custody.”

Accusations of gang ties appeared to be playing a role in ICE’s decision to send some of the teenagers to jail, but the evidence supporting those allegations was often flimsy and speculative. By 2018, MS-13 in particular was a favored justification for the Trump administration’s harsh immigration policies. Earlier that year the president himself had said, “these are not people, these are animals.”

That rhetoric appeared to explain the way ICE had treated many of the teenagers who’d been transferred to Cowlitz and NORCOR. From what Godoy could gather, some had been picked up during anti-gang operations like Operation Matador, which cast dragnets into Central American immigrant communities and profiled innocent teenagers. But regardless of how weak the evidence against the minors in its custody was, ICE was asserting the authority to hold them while they were placed into deportation proceedings, claiming that they were too dangerous to be released on bond or transferred to ORR.

“When evidence that slender is used to justify the indefinite detention of a child, I think we should all be deeply concerned.”

“One kid was found with a blue-and-white colored rosary that was flagged as MS-13 gang paraphernalia,” Godoy told me. “One can imagine many reasons why a kid might have a rosary. Maybe some involved gang activity, but I would suspect many of them don’t. When evidence that slender is used to justify the indefinite detention of a child, I think we should all be deeply concerned.”

As Godoy interviewed Ratcliffe and other attorneys who’d been representing the teenagers, she began to realize that there had been more of them than Cowlitz and ICE were letting on. One attorney estimated that at any given time there were between three and five in the facility. Later, a county official told a journalist that ICE had sent “roughly 30” juveniles to Cowlitz as of mid-2019.

ICE claimed that the teenagers had been locked up because they were a threat to the public. But Godoy had no idea what it had based those assessments on, and ICE was refusing to explain itself.

“That was one of the very early questions that led me to keep pursuing this,” said Godoy. “And I still haven’t gotten an answer to it. Why these kids? Why did these kids wind up in a jail and other kids wind up in an ORR facility?”

A FISTFIGHT AND A LOST CHILDHOOD

Rodriguez was born in a small town in southern Guatemala, close to the Pacific coast. When he was just a few months old his father passed away, and when he was 3, his mother set off for the United States, leaving him and his siblings in the care of their grandmother. At 11, he and his 12-year-old brother decided to join their mother. For two months, the pair walked through Guatemala and Mexico, sleeping in motels and along the roadside before eventually reaching America. (Bastian Rodriguez is a pseudonym — he and his attorneys asked that his identity be protected to ensure his safety.)

The pair joined their mother in the Maryland suburb where she lived and made ends meet working at a fast-food restaurant. Money was tight, and she suffered from severe health problems. Over time, Rodriguez’s brother began to fall in with a tough crowd, and without much else to do, he would tag along.

“She was working from 5 to 5, and we didn’t communicate,” he said. “So I got in trouble and started going to the street, because that’s where I got attention.”

Rodriguez’s brother joined MS-13, but Rodriguez says he didn’t follow suit. Some of his friends were in the gang, but he said he didn’t like the hierarchy and control so he kept his distance.

“I never was in it,” he told me. “I don’t like people telling me what to do, I like being with myself.”

But gang violence surrounded him nonetheless. When he was 14 and in middle school, a friend of his who’d joined one of MS-13’s rivals attacked and beat him with a baseball bat, making the assumption that because his brother was in MS-13, he must be as well.

Rodriguez’s brother told him that if he wanted to keep it from happening again, he would have to stand up for himself. Together, the brothers confronted the boy.

There is cell phone footage of what happened next. In it, Rodriguez’s brother and the other boy are grappling while Rodriguez struggles to pull something out of the boy’s hand. Eventually it becomes clear that it is a machete. After a few moments, Rodriguez manages to take the machete, carefully tucking it between his legs with the point directed away from his brother and the boy. Afterward, Rodriguez pulls back and out of the frame.

Rodriguez’s brother, a slender young teenager at the time, overpowers the other boy and pushes him to the ground, kicking and punching him a few times. At one point Rodriguez briefly returns to the scuffle and half-heartedly tries to kick the other boy. He misses. A few moments later, the fight is over. The boy gets to his feet, dusts himself off, joins his friends, and walks away.

Aside from the presence of the machete, it is an unremarkable altercation between boys. No blood is spilled, no serious injuries are inflicted, and there are no particularly shocking acts of violence.

“I had the machete, but I didn’t try to hurt him,” Rodriguez told me. “I just wanted to scare him and let him know to stop messing with me.”

But that fight would wind up costing Rodriguez the remainder of his teenage years. Although the other boy had taken it from him, the machete belonged to Rodriguez. A witness reported the incident to police, and he was arrested, convicted of assault and carrying a weapon, and sentenced to 18 months in juvenile detention.

Paloma Norris-York, a colleague of Ratcliffe’s and Rodriguez’s attorney, said that he was a “reluctant participant” in the fight and was following the lead of his older brother.

“It’s very clear that it’s his brother who was the aggressor,” said Norris-York. “You can see [Rodriguez] doing everything he can to ensure that nobody is injured by the knife.”

After serving his sentence, Rodriguez appeared before a judge, who released him from custody and placed on probation. More than a year and a half after the fight, he was going home to his family.

But his arrest had drawn the attention of ICE, and agents were waiting for him in the courtroom. When he walked out, they handcuffed him and took him into custody. Two months later, in December 2018, he appeared before another judge — this time in an immigration court — where he asked to be released on bond so he could live with his mother while he fought to stay in the United States.

Norris-York said that at the hearing, ICE submitted evidence that misrepresented Rodriguez’s background and case, claiming that he was in MS-13 on the basis of his being seen and arrested with his brother. Documents the agency had entered into his record also falsely suggested that he’d hacked the other boy with the machete and been charged with attempted murder — neither of which was true. The judge sided with ICE, and denied Rodriguez’s bond request.

“The juvenile judge had said you’re safe to go home, you don’t need to be in custody anymore so go be on probation,” said Norris-York. “And then with no change in anything, two months later an immigration judge says you’re dangerous so we can continue to detain you.”

ICE decided not to transfer Rodriguez to ORR, instead keeping him in its own custody and sending him to the Abraxas Academy in Pennsylvania, one of the three facilities Godoy had seen on the spreadsheet earlier that year. He was there for 227 days before being transferred across the country to Cowlitz in the summer of 2019.

A LIFE WITHOUT SKY

Conditions inside of Cowlitz were hard and austere. The jail had not been designed for long stays. Local kids who’d been sent there by Washington’s juvenile courts served short sentences, generally just a few weeks at most. But the teenagers in ICE custody were often there for months or longer.

The jail had no outdoor recreation area, so the only time Rodriguez and the other teenagers went outside was when they were shuttled back and forth from court appearances. Few, if any, of the kids that ICE had sent there received visitors; their families were far away and couldn’t afford the trip. Only a sparse list of possessions was permitted inside their cell: two personal photographs, a pack of playing cards, and a stick of lip balm

The "yard" at Cowlitz, which ICE has described as providing detained teenagers with outdoor recreation time.

Courtesy of Paloma Norris-York

The only books they were allowed to read had to come from the jail’s library, and only 10 or so of them were in Spanish, the language many of them were most comfortable with. Rodriguez and the others were mixed in with the kids from Washington, and at times the two groups butted heads. The locals later told Godoy that they had pitied those that got dubbed the “ICE kids.”

Like Rodriguez, many of the ICE kids came from backgrounds marked by trauma, but the only counseling services offered at Cowlitz were brief appointments with a case coordinator whom most of them were reluctant to open up to.

Rodriguez thought about giving up and asking to be deported to Guatemala, but Norris-York convinced him to wait, hoping that she could convince a judge to release him on bond.

“Every time someone left Cowlitz, I said, ‘Damn, when is it going to be my turn to walk out that door?’” he said.

In mid-2019, Godoy asked Dr. Amy Cohen, a psychiatrist who serves as a mental health and child welfare expert adviser to the Flores settlement agreement counsel, to carry out an assessment of the teenagers being held at Cowlitz by ICE. It didn’t take long for Cohen to conclude that the long, indefinite periods of detention were inflicting serious psychological damage.

“All the kids were put on medication, none of them knew the names of those medications or why they were on them and what they were supposed to be doing for them, and no psychiatrist saw them on any regular basis to evaluate the medications and whether they were helping or hurting,” Cohen said. “Around the whole issue of mental health there was tremendous negligence.”

Her assessment excoriated Cowlitz. She said that the “long hours of solitary time produces depression and anxiety symptoms, especially for those with trauma histories, which are present for all youth in this population.”

The ORR facilities Cohen had visited had their own problems, but in her judgment the difference between them and Cowlitz was “night and day.”

“The understanding among [ORR] staff is they are basically there to care for the children, not to control them, whereas the staff at Cowlitz are probation guards,” she said. “They’re not people who are child care workers, so these kids are treated as criminals.”

Inadequate mental health services at Cowlitz helped fuel a vicious cycle. The uncertainty and isolation were a toxic mixture. Inevitably, a teenager would snap and direct an outburst toward staff or other youth at the facility, which was then used by ICE as evidence for why immigration judges shouldn’t let them out on bond.

“They’re placed in this really stressful environment, away from their families, where they don’t know when — or if — they’re ever going to get out.”

Over the years of his incarceration by ICE and particularly in the wake of receiving word that he was not being released in late 2018, Rodriguez had gotten in a handful of minor scuffles with staff and other juveniles, although none that involved weapons or resulted in serious injuries.

“I mean, they’re teenagers,” said Ratcliffe. “They’re placed in this really stressful environment, away from their families, where they don’t know when — or if — they’re ever going to get out, they’re not given coping mechanisms, they’re not supported, and then they’re penalized for acting out.”

ICE had decided Rodriguez and the other teenagers in Cowlitz were “dangerous,” but it wasn’t giving them tools to overcome their traumas or escape that label. Alone, away from their families, and with no way of knowing when they’d be released, some just ran out of gas.

“There are cases in the records that we reviewed of kids who decided to give up and accept a quote-unquote voluntary departure back to their countries of origin even while they were still at Cowlitz before they turned 18,” said Godoy. “And it’s unclear whether they ever had representation in that process.”

IN THE SHADOW OF VICTORY

Godoy’s investigation and ICE’s obstinate refusal to provide information about Cowlitz had generated some local coverage of the minors detained there, but by the time she and her colleagues released their full report, it was April 2020. By then the Covid-19 pandemic had the country’s attention, and the national headlines that they felt ICE’s actions warranted failed to materialize.

“When you talk about family separation, of course at the border it was the most painfully visible example of that, but this is also an example of family separation,” said Enoka Herat of the ACLU. “The kids who have been detained in this kind of contract aren’t unaccompanied. They have family members and relatives in the U.S. that want them at home.”

But as the summer progressed and protests over the killing of George Floyd erupted, racial justice and immigrant rights advocates in the Pacific Northwest began to take notice of what was happening at Cowlitz.

“I was shocked, because I never thought that a small town could have a contract with ICE,” said Ricardo Rodriguez, a Cowlitz-based know-your-rights educator for the county’s immigrant communities. “So I said, I need to do something to close it. That’s when I started putting things together and asking, who wants to do this with me? And I was blessed, because I found a lot of people.”

He and other activists began organizing protests outside of the juvenile facility in Cowlitz. As the summer stretched on and local religious groups joined up, the demonstrations grew and began flooding the county commission with demands to end the contract. At public meetings, advocates and allies peppered commissioners with questions about the treatment of teenagers in the facility.

Protesters gather outside Cowlitz juvenile facility, calling for an end to the facility's contract with ICE.

Photo courtesy of Liz Kearny

“One time, one of the commissioners cut off one of the speakers to say, ‘You keep calling them children, but they’re not children,’” said Liz Kearny, co-pastor of the Longview Presbyterian Church. “They wanted to adultify these youth and paint them as criminals and violent and say that’s why they were being held. There was a lot of racist rhetoric.”

As the campaign picked up steam, Norris-York prepared for Rodriguez’s upcoming bond hearing — his first chance to be released in nearly two years. At her request, Cohen had conducted a psychological evaluation of him. Cohen didn’t believe he fit the profile of a gang member, with there being no record of him ever self-identifying as one, even to other teenagers in Cowlitz.

In her report, Cohen said it was clear that there was no reason to keep detaining Rodriguez, who was now 17 and, including his initial sentence for the fight, approaching his fourth year of incarceration. “There is nothing to indicate at this time that [Rodriguez] represents a danger to others,” she wrote.

Patty Fink and her son Peter lived not far from Cowlitz in a small town. They’d become involved with the campaign to end the contract, and through Facebook they’d heard about programs where families like theirs could become sponsors for detained minors. With the help of an organization called Every Last One, the two made contact with Rodriguez, who called them on a video link from inside Cowlitz. Almost immediately they felt a bond with him.

“It was obvious from the beginning that he was really reaching out and wanting not just his freedom, but to have someone to speak with,” said Peter, who at 19 was close to Rodriguez’s age.

Peter Fink led a campaign to release Bastien — dubbed "BBB" — for months.

Courtesy of Peter and Patty Fink

Rodriguez quickly decided he could trust the pair. “The little I started to know them, they’re good,” he said. “They have a good heart, you know?”

He told them that he’d been practicing yoga and mindfulness meditation at Cowlitz to keep himself grounded, saying that he wanted to get his GED and go to college. “He immediately was just really open and welcoming and interested in us,” Peter said. “And it really seemed like from the second or third Zoom that we were like family.”

Rodriguez had already decided that if he were released, he would stay in the Pacific Northwest. His brother had already been deported, and almost 18 now, he was looking for a fresh start. The Finks seemed like a way to make that happen, and they offered to open their home to him when he got out.

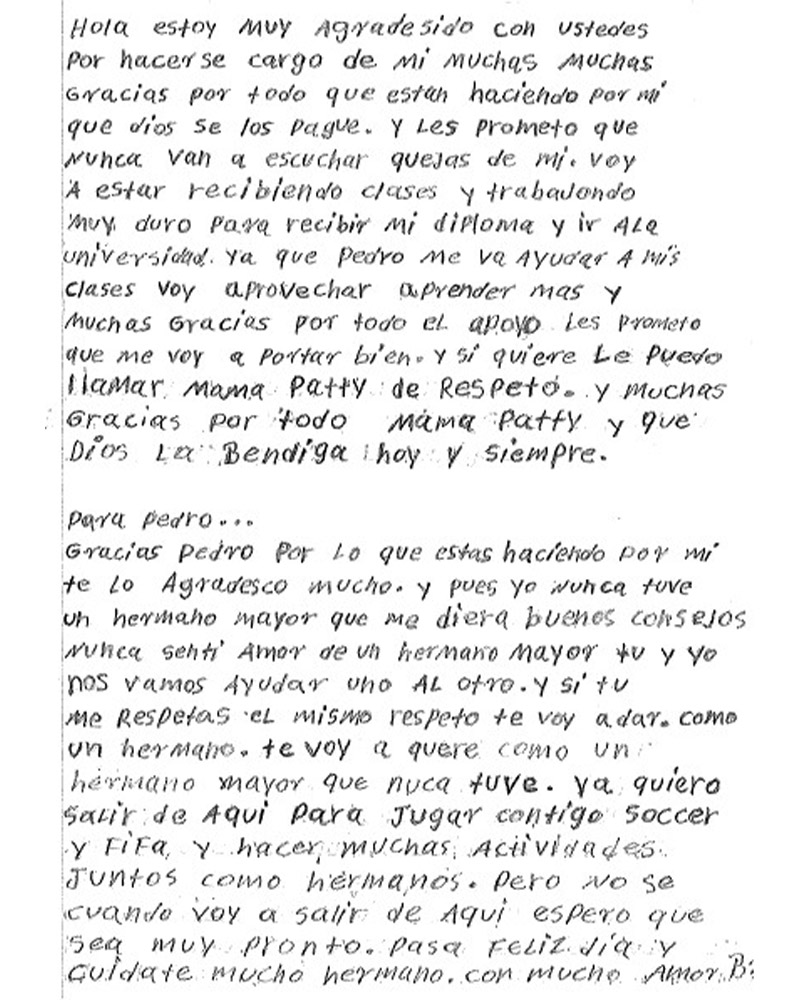

“Many, many thanks for what you are doing for me, may God reward it and I promise you will never hear complaints from me,” Rodriguez wrote in a letter to them. “I am going to be taking classes and working very hard to receive my diploma and go to college.”

A letter written by Bastien to the Finks from Cowlitz.

Courtesy of Patty and Peter Fink

As the date of his bond hearing approached, Rodriguez began to dream aloud of what he would do if he got out of detention.

“He would say, ‘Oh, you know this is what we’re going to do, we’re going to play soccer.’ Romanticizing what freedom would look like, talking about visiting the beach, and all these basic things that most folks take for granted every day,” Peter told me. One of the first things he wanted to do was visit a river and go fishing.

But in early November, Norris-York received bad news. ICE had convinced the judge that nothing had “materially changed” in Rodriguez’s case since his bond hearing two years earlier, and therefore there was no reason to hold a new one. There would be no hearing. After 530 days in Cowlitz, on his 18th birthday Rodriguez was going to be transferred to an adult detention center.

“When he found out, he was devastated,” said Peter. “We were devastated. It was just physically shocking to not be given that chance to have the dreams that we’d been planning out.”

Peter and Patty Fink knew that the decision was crushing for Rodriguez, who now faced the prospect of being the youngest person in the fourth largest adult immigration detention center in the United States. They were worried about him, so they arranged to drive to Tacoma to try and visit him on the day he arrived, hoping it would make him feel less alone.

But by the time they got there, Rodriguez was already being processed. Later that day, Patty spoke to him on the phone. He sounded despondent.

“He called, and when I hung up the phone I was in tears,” she said.

Without a bond hearing, there was no way to tell when his next opportunity to be released would come. His entire teenage years had passed by, and the pair began to worry that he was close to giving up.

“ICE never understood us,” Rodriguez told me. “They just said we were dangerous all the time, like Central American people are dangerous.”

While Rodriguez adjusted to life in Tacoma and Norris-York struggled to get a judge to review his detention, back in Cowlitz County the campaign to end the contract with ICE was gaining momentum. A week before Christmas, the Washington attorney general’s office wrote a letter to the Cowlitz County Commission saying that by allowing juveniles to be detained there without a criminal sentence, it was likely in violation of state law.

Cowlitz was a conservative area — Donald Trump had increased his share of the vote there from 53 to 57 percent between 2016 and 2020 — but the campaign was starting to crack the resolve of county policymakers. In early February, a panel of superior court judges responsible for overseeing the contract finally relented. After months of protests outside of the juvenile jail where the young immigrants had been held, the court was going to end the county’s contract with ICE.

NORCOR and Abraxas Academy had already decided to pull out of their own contracts, and with the court’s decision, all three of the facilities Godoy had uncovered in her research were ending their relationship with ICE. For the activists who’d campaigned against the contract, the superior court’s announcement was a major victory and proof that a vocal, resolute community can effect change. With nowhere to house the teenagers, it appeared that ICE would no longer be able to hold them in its custody. Godoy, however, was not so sure it was the end.

“Under the law, ICE has to disclose the use of such facilities,” said Godoy in February. “But they don’t have to make an announcement if they bring a new one online. And we have FOIA records requests that are at ICE’s doorstep that are over two years old now waiting for them to answer. So I’m not certain that in that two-year lapse they haven’t opened new jails like this.”

Godoy’s uncertainty turned out to be well-founded. When the ACLU initially asked whether the agency was seeking to establish new contracts in other municipalities, it was evasive, declining to answer straightforwardly and saying only that “in rare circumstances, ICE does contract bed space with state-licensed facilities to house both accompanied and unaccompanied minors with serious criminal histories.”

In April, advocates became aware that ICE had indeed arranged a new contract, this time with the municipal government of Winchester, Va. In May, the agency acknowledged that it had “secured another facility on the East Coast for the rare cases that require ICE to house accompanied minors without their parents.”

Under the new contract, a 16-year-old El Salvadoran boy who was held at Cowlitz along with Rodriguez is now incarcerated in Winchester’s juvenile jail. According to his lawyer, ICE is holding him because of misdemeanor convictions related to verbal threats he made against another boy who he says was bullying him.

Before news of the new facility broke, and around the same time that Washington activists were celebrating their victory in February, Norris-York and Rodriguez were preparing for their own quieter battle, and hoping that they too would also have a reason to rejoice. A judge had agreed to review Rodriguez’s detention at Tacoma — it would be his first shot at release since a month after he turned 16.

Since she met him, Norris-York had been urging Rodriguez to be patient and hold off on asking ICE to deport him until he had his day in immigration court. In early March, she gathered Cohen’s psychological assessment of Rodriguez, prepared her arguments, and appeared in front of the judge in a court inside Tacoma.

The hearing lasted an hour and a half. After listening to Norris-York and ICE state their cases and asking Rodriguez a few questions about the conditions inside Cowlitz, he issued his ruling. ICE had convinced him that Rodriguez was a danger to the community. He would remain locked up at Tacoma.

“ICE was never going to let him go,” Norris-York said. “In the end, the judge decided he was dangerous. So there was nothing anyone could do.”

Norris-York told Rodriguez he could keep fighting his case from inside Tacoma, but he’d already lost the entirety of his late teenage years to ICE. He was exhausted. Not long after the judge’s decision, he requested to be deported. He was going back to Guatemala.

“I was tired of being locked up,” he said. “I wanted to be free and finish school. So I decided to get deported. It was a hard decision.”

On April 24, Rodriguez boarded a plane and was deported to Guatemala, a country he hadn’t been to since he was 11 years old. ICE gave him two small egg sandwiches for the journey.

ON THE OTHER SIDE

A week later, I met Bastian Rodriguez in the small town where he grew up, 20 kilometers down a gravel road that stretches past fluorescent green pastures and modest houses in the rural Guatemalan countryside. He’d spent his first two days of freedom with his sister in the capital, but, fearful of gangs in her neighborhood, she’d refused to let him leave the house, so he left to visit his grandmother and remaining relatives.

Rodriguez boarded a plane and was deported to Guatemala, a country he hadn’t been to since he was 11 years old.

Peter and Patty had found a boarding school a few hours to the north in the volcanic highlands that was willing to take him in, and I’d come to bring him there. His grandmother, who ekes out a living selling ice every morning to her neighbors, thanked me for accompanying him to the school.

“God will help him achieve because he’s smart,” she said. “He doesn’t drink, and he doesn’t smoke.”

Rodriguez has a soft face ringed by a touch of teenage acne and a broad, effortless smile that complements his warm and approachable demeanor. He laughed and joked with his relatives, hugging them as he said his goodbyes before walking toward the waiting car with me. On the way, he pointed to a small soccer field where he remembered playing with his friends as a child. Whatever menacing specter ICE had been describing to immigration judges over the last two and a half years, Rodriguez far from fit the bill. In his Zoo York T-shirt, skate shoes, and backpack, he simply looked like what he is: a likable, awkward teenager.

As our car wound its way past mango plantations and picturesque rivers, Bastian talked about his favorite reggaeton artists (Miky Woods) and his gratitude for the work Norris-York put into his case.

“She did everything for me,” he said.

When the conversation turned to ICE, however, his voice dropped an octave and his gaze fell.

“They don’t care about anything. They just wanted me deported, that’s it.”

Halfway through the ride, we stopped at a restaurant. Over a plate of grilled chicken and fries, Rodriguez spoke about the fight that led to his arrest so many years ago. He regrets it, but swears he didn’t want to hurt the other boy, just to scare him off.

“I know I did something wrong and I needed to pay, but not like that,” he said.

He told me that he’s happy to be free finally, but that he’s worried about being back in Guatemala. It’s an unfamiliar place now, and he isn’t sure how to move around. While he was in Cowlitz, he had a friend ink him with small homemade tattoos, and he was nervous that the police might mistake them for gang symbols. On his right cheek, he has a tiny broken heart, which he said symbolizes the pain of never meeting his father and having his mother leave when he was 3. On the left cheek, a small cross because “Jesus all the time protects me.”

I asked what excited him most about the new school. He smiled, and said, “Girls.” I thought about how much he’s missed out on — an entire swath of his formative years lost to America’s immigration detention machinery.

A few hours later, we climbed a steep hill in our small Toyota, ascending toward his new school as a vista of mist-covered volcanos and rain clouds stretched out beside us. As we neared, he became visibly nervous, mumbling lyrics to the song playing in his headphones and asking me whether I think he’ll have to wear a uniform.

“What if I don’t make any friends?” he asked.

The school is an opportunity for him to finish his education, a blessing provided by Peter and Patty as well as other community activists in Washington who’ve raised money to support his transition. But for an 18-year-old in a strange place, fresh off the heels of years spent in carceral detention, how that transition will play out remains unknown.

“He’s been living in the institutional setting of a juvenile hall, and that’s a really warped environment to be in,” Norris-York told me a few weeks earlier. “He’s had trauma in the past, and then this whole experience has been another level of trauma. So I worry about how successfully he’ll be able to adjust to another communal living setting.”

As the principal of the school showed him around, describing its history and ethos in an upbeat voice as we passed framed pictures of Catholic priests and large wooden crosses, Rodriguez was quiet, pensively searching for his bearings in the new, unfamiliar world. The principal guided us to the small room they’d arranged for Rodriguez, stark and bare with a bed and a small table. When he left, Rodriguez sat on the bed.

“I feel lost, man” he said after a long pause. “I don’t know nothing about this place. I got no friends here. What am I going to do?” As night fell, I wished him luck and departed.

A few days later, he texted me. The school’s administrators wouldn’t permit him to leave the campus, and he was thinking about dropping out. “I was already locked up for a long time. I don’t want to be anymore,” he wrote.

In mid-February, the Biden administration sent a memo to ICE ordering it to focus its resources on deporting immigrants who fall under one of three “priority categories.” But while the number of deportations carried out by ICE fell to an all-time low in April, it is unclear how — or whether — the new guidelines will affect teenagers like the one being held in Winchester, who remain in the same endless detention that pushed Rodriguez to let go of his ties to the United States. And while ICE says that the boy in Winchester is currently the only minor in its custody, there is no law, policy, or directive preventing the agency from incarcerating others whenever and wherever it sees fit, with no oversight or obligation to explain its reasoning to the public.

“I firmly believe that the human rights of the youth at Cowlitz in ICE custody were violated,” said Norris-York. “I think it’s very clear, and I think that was very damaging. The fact that youth were kept in conditions that no adults are kept in, whether in immigration detention or federal prison, for over a year, shows that something is gravely wrong with the system.”