“They Don’t Care if You Die”: Immigrants in ICE Detention Fear the Spread of COVID-19

Mario Rodas, Sr. first found out there was a deadly virus spreading through the country while he was watching television at the Plymouth County Correctional Facility in Massachusetts. In early March, Rodas had been pulled over and arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents while driving to the supermarket with his wife, a legal resident and the mother of his three U.S. citizen children. Since then, he’d been in the custody of ICE, mostly at Plymouth.

The more Rodas heard about the disease, the more fearful the 59-year-old became.

“I was scared for my health,” he told the ACLU. “I was worried because I have diabetes, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure. It was stressful, you know?”

Just days later, word spread through the prison — a staff member had tested positive for Covid-19. When they heard the news, Rodas’s son — also named Mario — and the rest of his family were terrified.

“Just do whatever you can to stay alive and hopeful,” he said he told his father over the phone. “We are doing everything we can to get you out of there.”

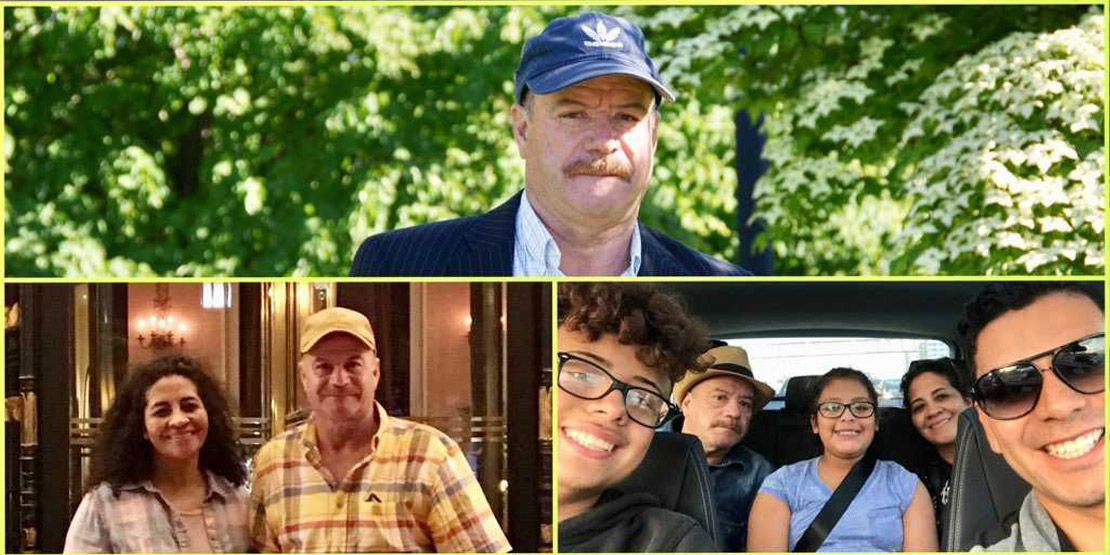

Mario Rodas, Sr. in family photos with his wife and children.

Across the country, there are nearly 36,000 people in the custody of ICE on an average day. Some are in county jails and state prisons, others are in facilities run by private contractors like the GEO Group. Many are asylum seekers who have asked the U.S. to protect them from persecution abroad. Others — like Rodas — are undocumented workers who lived in the U.S. for years before being swept up by ICE.

Now, public health officials say that overcrowding and poor access to sanitation inside ICE detention facilities is a crisis in the making, with two doctors contracted by the Department of Homeland Security calling them a “tinderbox” for infections in a letter to Congress on March 19.

“As local hospital systems become overwhelmed by the patient flow from detention center outbreaks, precious health resources will be less available for people in the community,” they wrote.

Across the country, tensions are rising inside of ICE facilities, with detained immigrants and their families fearing that cramped conditions and an indifferent bureaucracy are a deadly threat to their safety — and to the wider public’s health. So far, at least 20 detainees and dozens of staff at facilities housing them are confirmed to have contracted COVID-19. Many others are under quarantine, raising fears that the virus is spreading undetected and potentially infecting guards who shuttle in and out for their shifts before returning home.

These numbers are likely a significant underestimate due to shortages of COVID-19 tests. In a hearing last week on an ACLU lawsuit, an attorney working for the government admitted that there were no tests available at two Maryland facilities, while simultaneously arguing that detainees there were not at risk due to the lack of confirmed cases. ICE has said they aren’t required to disclose information about staff at privately-run detention facilities who have tested positive.

“The nature of these facilities is such that it’s really impossible to engage in the social distancing that we’re all practicing right now,” former director of ICE John Sandweg told Democracy Now.

After the staffer at Plymouth fell ill, Rodas said that guards started bringing him and the others in his cell block to meals in shifts. But each group was still as large as 80 people at a time, and none were given masks or gloves to wear.

“The government is asking everyone to stay home and not have physical contact with other individuals. But meanwhile, my dad was out there amongst 80 to 150 other individuals, and you don’t know if they could potentially have something and be contagious,” said Rodas’s son.

Realizing the danger he was in, Rodas’s lawyer, Kerry Doyle, reached out to friends at the ACLU of Massachusetts. On March 25, the ACLU filed a petition asking a judge to order ICE to release Rodas along with another detained immigrant on the grounds that their medical conditions placed them at high risk for COVID-19 complications, in violation of their constitutional rights.

Two days later, Rodas received word. He would be able to go home.

“They released him on pretty strict conditions,” said Doyle. “He has a GPS bracelet.”

Rodas’s son rushed to Plymouth to pick him up. “I was so happy, I couldn’t believe it,” he told the ACLU. Now, Rodas is quarantining in a room in the house until 14 days have passed since his release.

“I think that the whole thing highlights how easy it is for immigration [authorities] to release detainees that have cases that are low priority and allow them to go back home during these very uncertain times,” said his son.

Mario Rodas, Sr. being released from Plymouth County Correctional Facility on March 27th.

Mario Rodas, Jr.

The suit that led to his father’s release was one of a series that have been filed across the country in recent weeks seeking similar orders. Fifteen were filed by the ACLU and its affiliates, with over thirty people released from detention as a result of those suits so far.

Alfredo Garza was one of those lucky few. He was released on March 26 from the Tacoma Northwest Detention Center, a private facility run by the GEO Group in Washington, following a suit filed by the ACLU and the Northwest Immigrant Rights Project. Garza suffered a heart attack while detained this past January and says he was chained to a bed in the hospital while receiving treatment.

“Doctor care is terrible there,” he said. “The worst there is.”

In 2018, an investigation by Seattle Weekly revealed that the Tacoma facility had been providing substandard medical care to immigrants housed there.

Washington was the first state in the country to experience a substantial outbreak of COVID-19, and in early March Garza says that he and others in the facility became afraid when another detainee fell ill with what they assumed was COVID-19.

“They took him out in a suit, like one of the people who catch bees,” he said.

Geo Group and ICE have not confirmed any cases of COVID-19 in Tacoma Northwest Detention Center, but Garza says that his unit was placed under quarantine and kept away from contact with others anyway:

“We said, ‘Hey we need sanitizer or chlorine.’ But they said, ‘No, we don’t have any.’”

After the ACLU’s suit was filed, Garza was released along with another detainee who suffers from high blood pressure. Since then, 80 people housed in the facility have gone on hunger strike to raise attention to the danger they say they face from the pandemic.

“I have a friend who has diabetes and he was worried when he found out that there were people with coronavirus inside,” Garza said. “They didn’t even tell him, ‘Hey, we are going to put you somewhere else’ or ‘We’re going to do something.’ They don’t care if you die.”

Despite widespread calls from public health experts that the detained population must be drastically reduced in order to prevent COVID-19 from spreading unchecked and taxing the healthcare system, so far ICE has largely refused pressure to release people in its custody.

On Tuesday, the agency indicated it had identified 600 detainees deemed "vulnerable" to COVID-19, and released 160 of them. But that same day, lawyers for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) asked a judge to stay a ruling that would have released 22 detainees with medical conditions from two county jails in Pennsylvania.

"Families were getting ready to pick up their loved ones when the stay came down," said Michael Tan, Deputy Director of the Immigrants' Rights Project at the ACLU. "ICE is playing an unacceptable game of Russian Roulette with people's lives."

Karlyn Kurichety is a supervising attorney with Al Otro Lado, a California-based organization that provides legal services to asylum seekers and other immigrants. She says that her clients in the Adelanto ICE Processing center — another Geo Group-run facility — are scared.

“It’s just cruel and really disturbing, there's basically no precautions being taken,” she said. “The detainees are not given any information about COVID-19. There are no signs, no talks, no advisories, nothing of that nature.”

Adelanto has put strict measures in place requiring visiting attorneys to wear N95 masks — despite the fact that even health care workers in the state aren’t able to find them. Since then, Kurichety says she hasn’t been able to visit her clients —most of whom are asylum seekers — or arrange a non-recorded phone call to discuss their case.

Recently, she says she spoke with one client who told her that two people in his dorm collapsed with symptoms that sounded like those of COVID-19. The dorm was subsequently placed under quarantine. Another said that he’d been cleaning his cell with body wash.

“It’s like if you wanted to design a situation where a virus would spread, this is what you’d do,” she said.

On March 30, the ACLU filed suit on behalf of six detainees in Adelanto with serious medical conditions, arguing that “without a rigorous testing regime, it is impossible to conclude that COVID-19 has not already entered Adelanto.”

Two days later, a federal judge ordered all six released.

But Kurichety says that those who remain are fraying emotionally.

“They’re really scared. I would say it’s almost like panic,” she said. “Their families, too, because we've been talking to their sponsors and sometimes they break down in tears. They're really frightened for their loved ones.”