For Love and For Life, LGBTQ People Are Not Going Back

The American Civil Liberties Union has influenced, and been influenced by, U.S. social movements since its founding in 1920. One of the most significant examples is the LGBTQ movement. Since the 1950s, organizers working in tandem with ACLU advocates have shaped the fight for justice and equality for LGBTQ communities as well as people living with HIV and AIDS. What is not generally known is that many early LGBTQ organizers were also ACLU members.

As an organizer myself, the significance of the ACLU to the early efforts of LGBTQ activists became obvious during my years as staff for the Northern California affiliate from 1978 through the mid-1990s. It was in San Francisco that I met and learned the histories of some of the earliest members of what was then called the “homophile movement.” Their work was multifaceted.

“We were fighting the church, the couch, and the courts,” legendary lesbian activist Del Martin often said when recalling the beginning of LGBTQ organizing. In doing so, she succinctly summoned forth for younger generations like mine the array of social, cultural, and legal institutions confronted by activists in the 1950s and 1960s.

Lesbian activists Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon are seen here in June 1988 at a gallery in New York City for their lecture that was part of the celebration for the opening of the exhibit, "Prejudice and Pride: The New York City Lesbian and Gay Community, World War II to the Present."

Morgan Gwenwald, courtesy Lesbian Herstory Archives

Del Martin and her partner of more than 50 years, Phyllis Lyon, got involved in organizing lesbians after meeting with three other female same-sex couples in San Francisco in September 1955. Their discussions that night about the lack of safe social options for lesbians led to the founding of a secret social club, which they named the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB). The group’s name was purposefully vague so as to provide a shield for any woman who was bold — or desperate — enough to join. In 1955, the concept of “gay rights” was not yet on anyone’s horizon. But civil liberties were.

The Executive Director of the ACLU of Northern California Ernest Besig, seen here in the 1980s.

Shirley Nakao

Within the first year of launching DOB, ACLU members Martin and Lyon invited Ernest Besig, the executive director of the ACLU’s Northern Calfornia affiliate, to a meeting in San Francisco. He spoke to a small group of women on July 5, 1956, advising them to educate themselves about their rights. He also acknowledged the vexing problem of the local police. Both San Francisco law enforcement and agents with California’s Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control could and did raid gay bars and arrest patrons. Many women and men pled guilty and paid a fine, not knowing that merely being in a gay bar was not against the law at that time. They had little to no choice. Even the threat of arrest could cost them dearly, as it was not uncommon for gay men and lesbians — as well as gender non-conforming individuals or those assumed to be LGBTQ — to lose jobs, homes, or even custody of their children if they were caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. There were very few places to turn for assistance. The local ACLU was one of them.

A handful of affiliates were willing to meet with LGBTQ advocates in the 1950s and early 1960s. Some sent speakers to homophile meetings, which also featured a small number of psychologists, educators, politicians, and religious leaders. Some affiliates also challenged local laws against LGBTQ bars, restaurants, and other meeting places.

Their involvement, while not always successful, opened the door to increased collaboration.

Unlike the affiliate offices, the national ACLU took a very measured approach to LGBTQ issues until the 1960s, entering the fray mostly on First Amendment grounds in the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s. The official position of the ACLU in 1957 was that there was no constitutional basis on which to challenge felony arrests for “homosexual acts,” but that “homosexuals, like members of other socially heretical or deviant groups, are more vulnerable than others to official persecution, denial of due process in prosecution, and entrapment.” Such matters were deemed to be “of proper concern to the Union.”

Local laws requiring the registration of people convicted of “homosexual acts” were condemned as unconstitutional. Still, the ACLU affirmed its 1957 policy, and that of President Eisenhower’s Executive Order 10450, which declared the use of “homosexuality” as a factor in determining federal government security clearances as valid, but “only when there is evidence of other acts which come within valid security criteria.” This rather tepid statement on the rights of gay men and lesbians was met with thanks from many homophile activists, who still saw possibiities for a more robust relationship with the organization despite the limitations of its national policy.

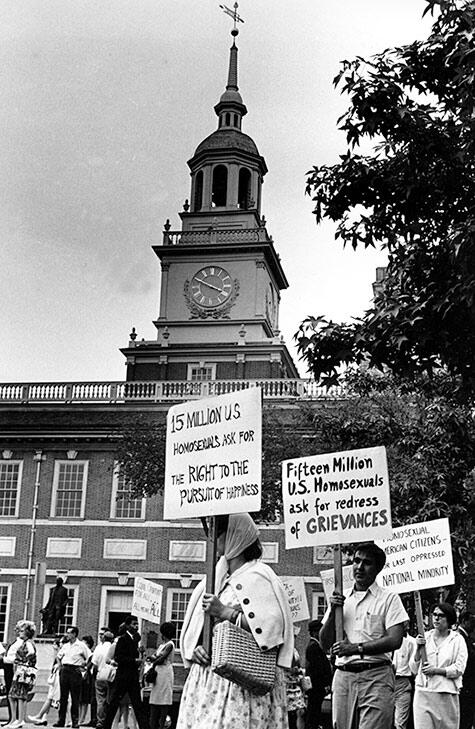

Demonstrators carry signs calling for protection of homosexuals from discrimination as they march in a picket line in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, July 4, 1967.

AP Photo/John F. Urwiller

“Gay is Good”

When sociologist Vern Bullough moved to Los Angeles in 1959, he immediately joined the Southern California affiliate and began meeting with its director Eason Monroe to help change the national ACLU’s policy on homosexuality. In San Francisco, the outrageous behavior of the police at the 1965 New Year’s Ball for the newly-established Council on Religion and the Homosexual brought ACLU of Northern California attorney Marshall Krause to the defense of those arrested for merely attending a private event.

Franklin Kameny, an astronomer fired from federal employment for refusing to deny being gay, was elected to the Washington D.C. affiliate’s board of directors in the 1960s and helped change organizational policy there. Kameny also helped nudge the homophile movement from education to action, coining the phrase “Gay is Good” and organizing annual pickets of neatly-dressed women and men at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall from 1965 to 1969.

These small, silent demonstrations at an American landmark, which were held for five years over the July 4th weekend and dubbed “Annual Reminder Days,” were among the first public protests by LGBTQ people in the U.S.

The peaceful participants were mostly young and white, with a handful of Black activists such as Ernestine Eckstein, and other activists of color. These LGBTQ protestors took personal risks when they were photographed and interviewed by the media during pickets in Philadelphia and in Washington, D.C. in the mid-1960s, but they were insistent that the movement bring public attention to the government’s denial of basic rights.

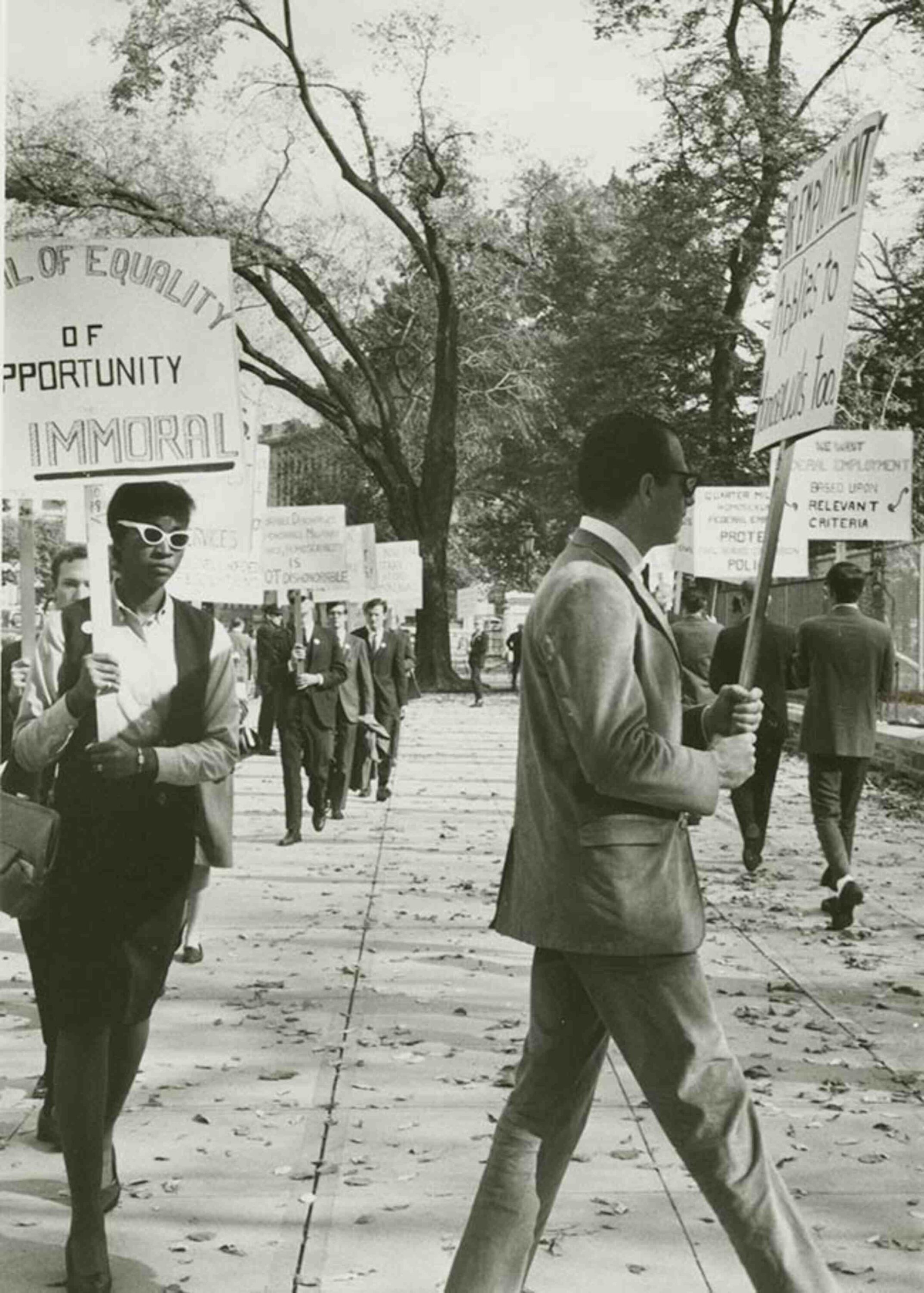

Ernestine Eckstein and unknown gentleman in picket line, 1965.

Photo by Kay Tobin ©Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library

Eckstein, who used this name as a pseudonym in her LGBTQ organizing, was a leader of the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) in New York during the 1960s. She had experience working with civil rights organizations such as the NAACP as a college student in Indiana before moving to Manhattan in the early 1960s; she joined the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) shortly thereafter. She became vice president of the New York Chapter of DOB in 1964 and for the next four years was an influential leader who urged the group and the movement in general to engage in more direct action efforts.

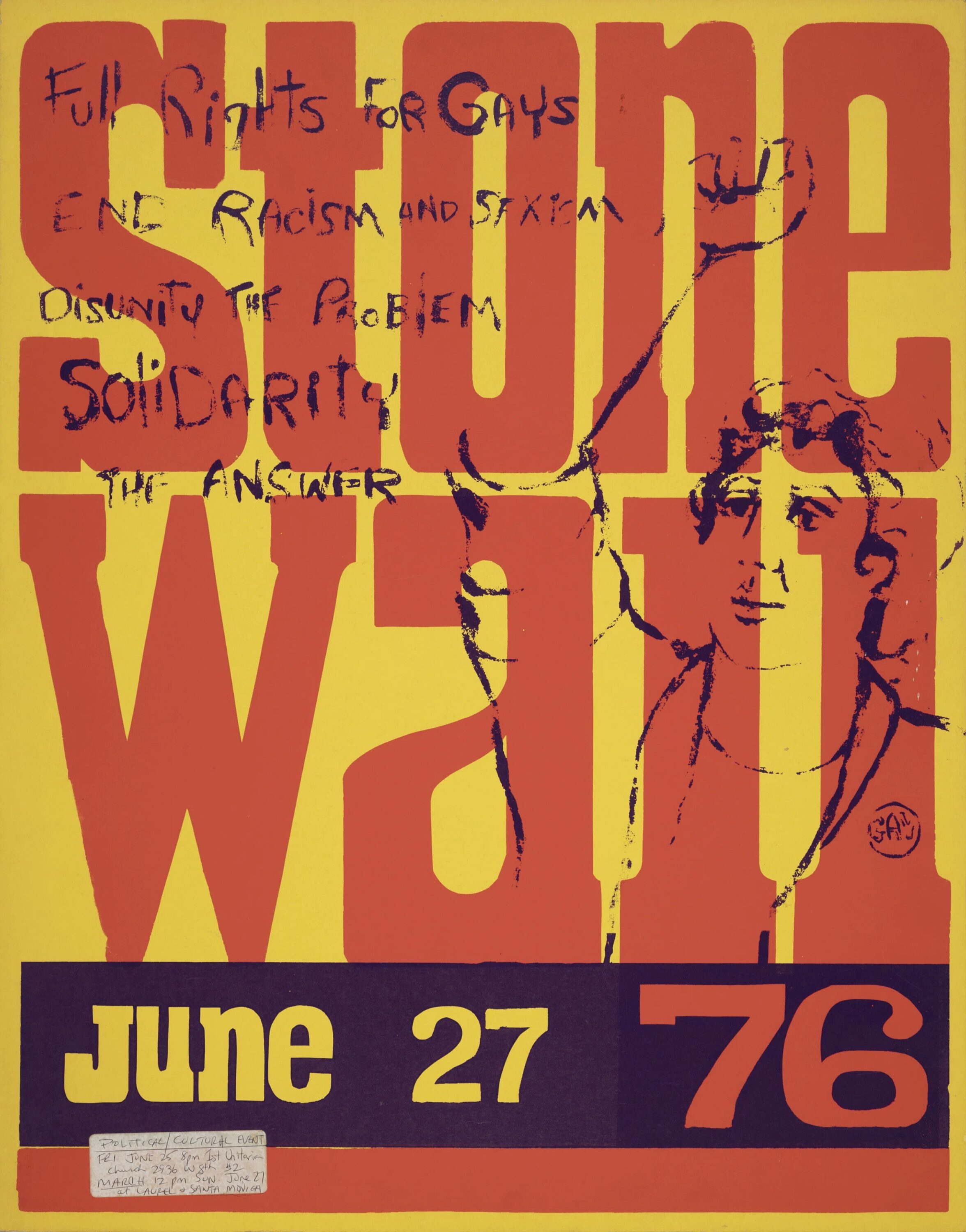

Stonewall: June 27, 1976 poster

University of Southern California, ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, used under CC BY-NC 4.0

LGBTQ Organizing Within the ACLU

In 1966, the first ACLU Lesbian and Gay Rights Chapter was formed in Los Angeles. The ACLU Foundation of Southern California formally affirmed that the right to privacy in sexual relations is a basic constitutional right and defended a public school teacher threatened with the loss of his teaching credentials after he was acquitted of charges of illegal homosexual conduct.

In 1967, two years before the 1969 Stonewall Riots in New York City — often misidentified as the start of today’s LGBTQ movement — the national ACLU formally endorsed the principle of gay rights, affirming its opposition to government regulation of private, consensual sexual behavior between adults, as well as police harassment of gay male and lesbian bars.

The following year, the organization brought the case of Boutilier v. INS, an unsuccessful challenge to the federal government’s deportation of a U.S. permanent resident who had been arrested on a sodomy charge in 1959. It was one of the most important gay rights cases to reach the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1950s, ‘60s, or ‘70s.

The 1970s saw a surge of visibility and activism as well as litigation on the local and national levels. In 1970, the ACLU of Southern California obtained an injunction that facilitated the first Christopher Street West march commemorating the Stonewall Riots, the precursor to what would become known internationally as Pride parades. In 1971, the ACLU filed Baker v. Nelson, the first lawsuit challenging state laws forbidding same-sex marriage. Baker was brought by two gay male activists at the University of Minnesota after local and state officials denied their request for a marriage license. Their request for review by SCOTUS was answered in one sentence: “The appeal is dismissed for want of a substantial federal question.”

In 1973, a momentous year that capped a decade of agitation led by Kameny and another ACLU member, New York Daughters of Bilitis leader Barbara Gittings, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. This significant step forward for the movement meant that those who opposed gay rights could no longer claim a valid link between homosexuality and mental illness. When I spoke with her years later about this victory, Gittings wryly noted, “All of a sudden, we were cured!”

That same year, the national ACLU formed the Sexual Privacy Project, one of the first projects of its kind based in a civil rights organization. In addition to litigation and lobbying, they began to address gay issues internally with education and policy debates. They brought legal challenges that included, among others, defending a Washington state teacher who was fired for being gay and a Washington D.C. gay man who was denied a security clearance.

Throughout the country during the 1970s and 1980s, ACLU affiliates strengthened and expanded their work with local gay communities. When the ACLU of Northern California started a Gay Rights Chapter in 1978, one of its founders was longtime ACLU member Florence Jaffy, who had been the research director for the Daughters of Bilitis in the 1950s and 1960s. She insisted that basic information about the lives and experiences of LGBTQ people would help advance “the cause” and created the first collection of data on lesbian lives, published in the DOB magazine, “The Ladder,” in 1958.

Although it was not until years later that I learned more about her important role in the LGBTQ movement, I knew Jaffy then as an elder activist who had spent decades working as an educator. I later discovered that, like some of the early activists such as Eckstein, she used Florence Conrad as a pseudonym in her work with DOB. As LGBTQ organizing became more visible and vocal in the 1970s, the need for such protections diminished.

ACLU affiliates in other states also aided LGBTQ activists in their organizing during the 1970s and 1980s. The ACLU of Nevada’s Human Rights Committee helped launch the first gay newspaper in the Silver State in 1978, and was integral to the community’s early organizing efforts in Las Vegas. According to historian Dennis McBride, director of the Nevada State Museum in Las Vegas, in 1977, “It was the ACLU [of Nevada] that made the first appeal to the gay community to organize.” The ACLU of Illinois also put its resources to work for LGBT and HIV advocacy. In the early 1980s, through litigation, education, and organizing, the affiliate took the lead in fighting discrimination against gay men and others living with HIV.

ACLU Lesbian Gay Right Project staff counsel Nan D. Hunter speaking in 1986.

Helayne Seidman

“For Love and For Life, We Are Not Going Back”

In spite of these gains, the use of states’ sodomy laws to target gay people intensified in the 1970s and beyond. Such laws were invidious yet effective tools for denying gay men and lesbians full citizenship, and served as significant roadblocks for the movement.

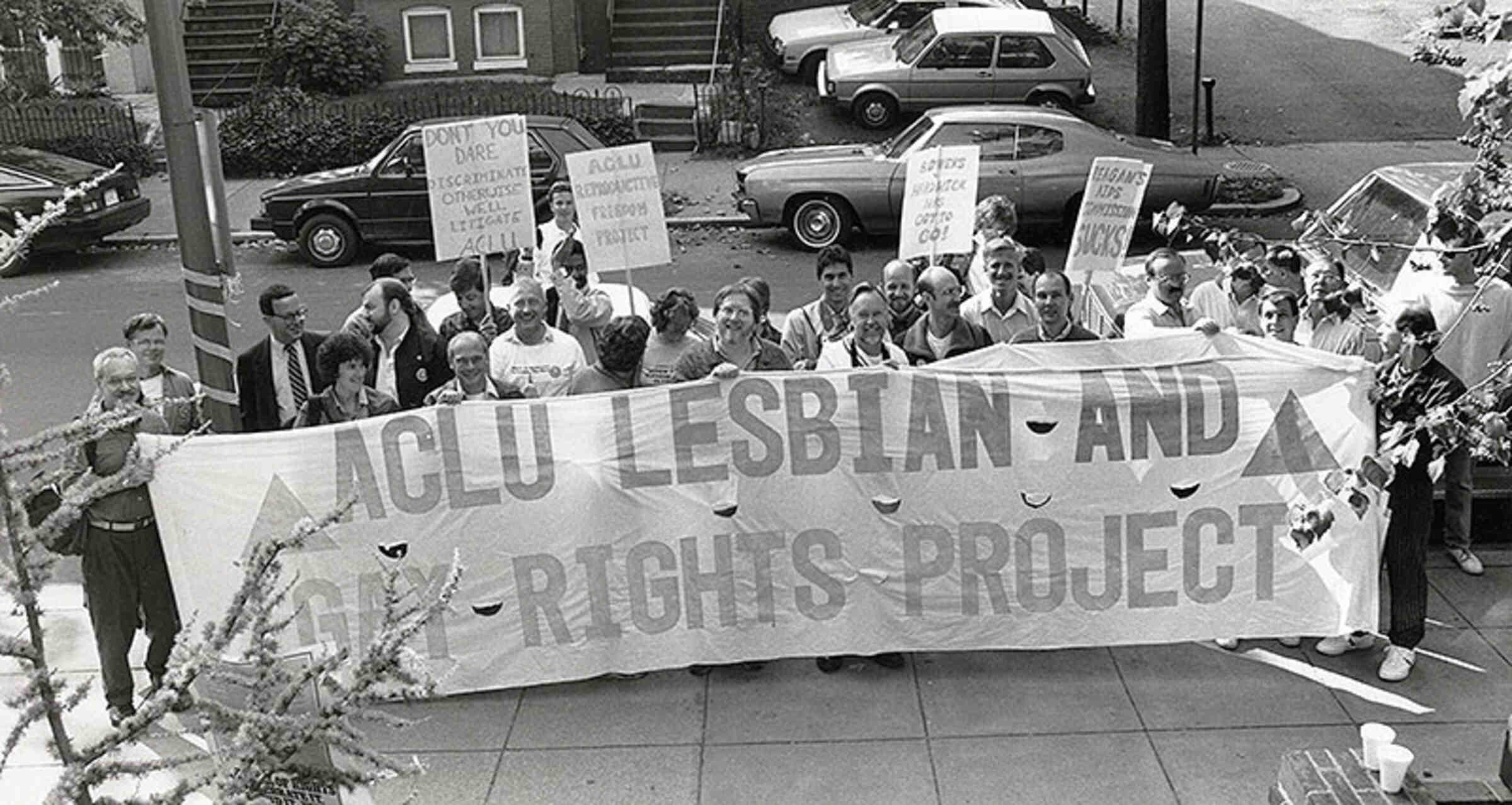

In response, LGBTQ rights advocacy accelerated at the ACLU in 1986. That June, the national office established the Lesbian/Gay Rights Project — now the LGBT & HIV Project — with reproductive rights expert and attorney Nan Hunter as its first director. As she later recalled, it was “a hell of a month” to launch the new project.

Within weeks, the U.S. Supreme Court issued the infamous Bowers v. Hardwick decision, which held that state laws criminalizing consensual sex were constitutional when applied to same-sex relationships. As ACLU lawyers and others have noted, the decision’s “utter contempt” was striking.

The court said that it was “facetious” to argue the fundamental right to privacy protected gay people, and said that there was no connection between marriage, family, and heterosexual intimacy, and intimacy between same sex couples. Relying on an erroneous understanding of the history of sodomy laws in the U.S., the decision also revealed the persistence of an ugly homophobia still permeating American institutions, fueled by the growing visibility of the LGBTQ movement as well as the increasingly fierce AIDS pandemic.

"ACLU LESBIAN AND GAY RIGHTS PROJECT" banner, seen before a march. Four individuals are holding signs that read "DON'T YOU DARE DISCRIMINATE OTHERWISE WE'LL LITIGATE ACLU," "ACLU REPRODUCTIVE FREEDOM PROJECT," "BOWERS V. HARDWICK HAS GOT TO GO!" and "REAGAN'S AIDS COMMISSION SUCKS!" 1987

Tom Tyburski, 212-607-3300, 201-417-7298

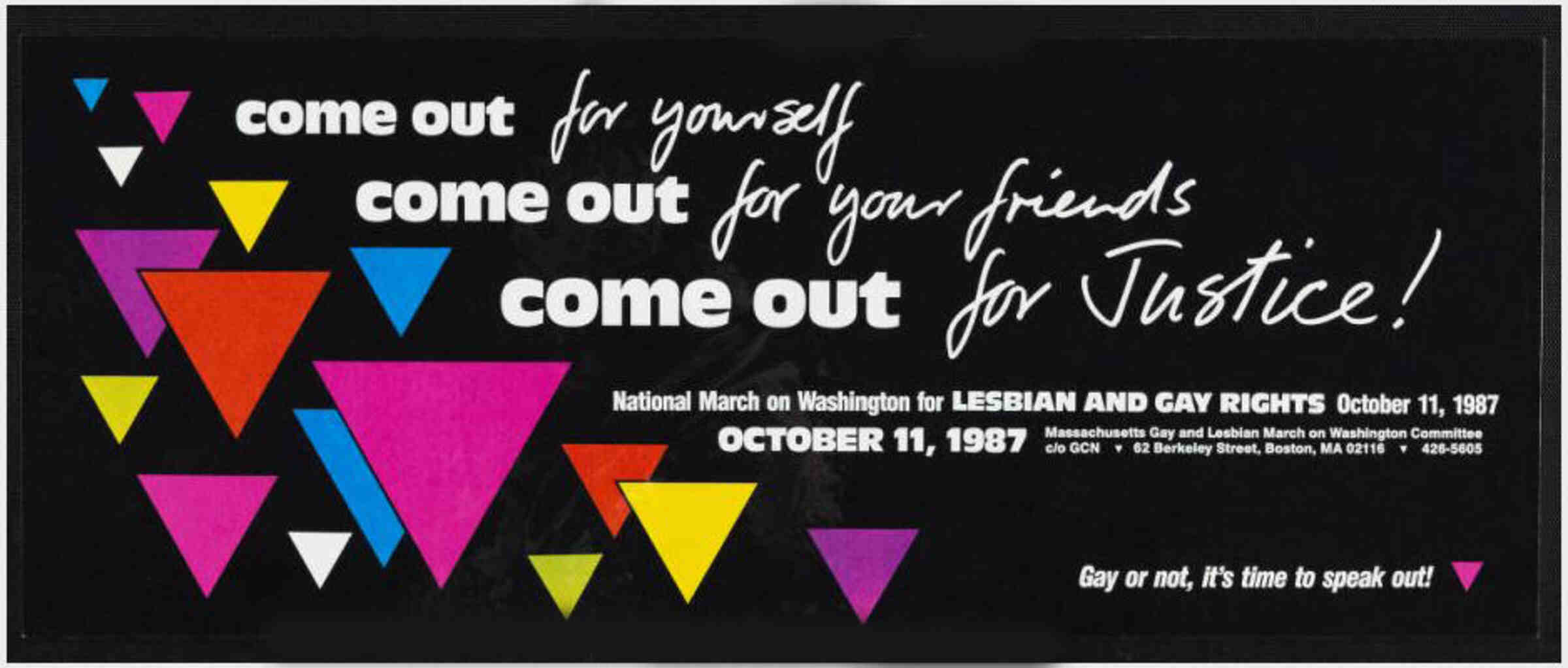

Activists throughout the U.S. mobilized for a massive response. The October 1987 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, with its rallying cry of “For love and for life, we’re not going back,” drew more than 300,000 people to protests in Washington, D.C. As the HIV/AIDS crisis was nearing fever pitch, I joined this phenomenal effort with my lover, two brothers, and sister-in-law. It was unprecedented. Eight hundred demonstrators were arrested after they engaged in nonviolent civil disobedience on the steps of the U.S. Supreme Court building in protest of the Bowers decision. In addition to the first unveiling of the AIDS Quilt on the Mall, 2,000 same-sex couples and several thousand supporters also staged a mass wedding outside the offices of the Internal Revenue Service to protest their lack of access to legally recognized marriages.

This marked the first large-scale action in support of same-sex marriage in America. When my partner and I were interviewed after the “wedding” by a reporter from San Francisco, we emphatically stated that we participated because we believed in fighting for our rights and hoped that such demonstrations would be a vehicle for LGBTQ equality. (This contrasted markedly with the response of our two gay male friends, who happily rhapsodized about being able to celebrate their love so publicly.)

Poster for the 1987 March on Washington, DC, supporting Lesbian and Gay Rights

University of Southern California, used under Creative Commons license https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

At the ACLU, the Lesbian and Gay Rights Project’s second director, William Rubenstein, helped further expand the organizational commitment to gay and lesbian rights, including AIDS-related issues. Rubenstein and his team, working with affiliates, challenged the Reagan administration’s lackluster response to the expanding public health crisis and fought for lesbian and gay families, teachers, and members of the military. The team challenged the Clinton administration’s nefarious 1993 “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, which silenced or severed from service members of the U.S. military who were openly lesbian or gay.

ACLU Lesbian and Gay Rights/AIDS Project Director Matt Coles

In 1995, Matthew Coles, with whom I worked when he was staff attorney at the ACLU of Northern California, became project director. He and the ACLU faced the challenges of homophobic executive actions during Clinton’s second term, such as the president’s 1996 signing of the Defense Of Marriage Act denying the validity of same-sex marriages and allowing states to refuse to recognize such marriages performed in other states. Activists and advocates nationwide also faced an onslaught of state ballot measures limiting gay rights in this period.

One of the bright spots during this era of backlash was the U.S. Supreme Court case Romer v. Evans, which challenged a Colorado constitutional amendment blocking state action to protect gays and lesbians from discrimination.

As Coles wrote in September 1995, discussing the pending SCOTUS decision in Romer, “If the U.S. Supreme Court upholds the Colorado Supreme Court's decision, we will be guaranteed the right to ask for the same civil rights protection that any other group in America can ask for. If it does not, in Colorado lesbians and gay men alone will be prevented from ever getting civil rights protection unless we convince the voters to change the rules again.”

In 1996, the ACLU and Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund won a landmark victory in the case. Romer was the first significant U.S. Supreme Court ruling for LGBTQ rights: a majority of the court recognized that gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people could not be deprived of hardwon victories at the ballot box. Romer was especially important in light of the Court’s decision in Bowers v. Hardwick just 10 years earlier.

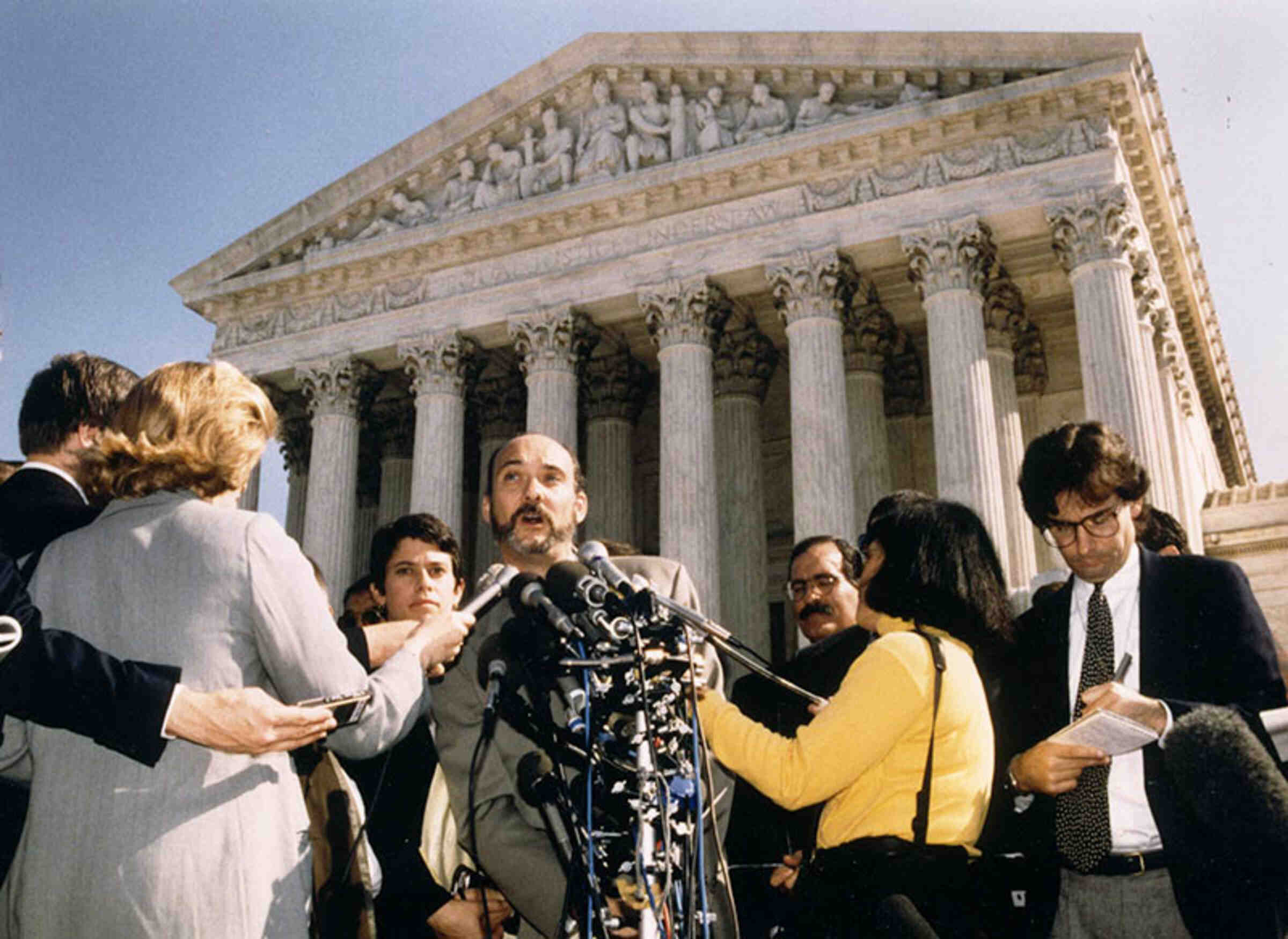

ACLU LGBT/AIDS Project Director Matt Coles speaking to the press after arguments in Romer v. Evans. Attorney Suzanne Goldberg stands behind him, 1996.

ACLU

Then came Lawrence v. Texas. It was a fitting start for the 21st century fight for LGBTQ legal rights — a complicated case beginning with the circumstances surrounding the arrest of plaintiffs John Lawrence and Tyrone Garner. However, thanks to the work of gay community members in Texas, the case was brought to the attention of Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund attorneys.

Lambda assembled a phalanx of legal arguments against sodomy laws, with 16 amicus briefs — including briefs from the ACLU as well as LGBTQ historians — that provided substantive reasons for overturning existing state laws criminalizing same-sex sodomy. The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2003 decision, which an ACLU statement noted “overruled Bowers in unusually strong terms,” affirmed unequivocally the constitutional rights of LGBTQ people to form intimate relationships.

In an unprecedented moment for the movement and a supremely unusual admission on the part of the court, Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy declared that its previous Bowers decision “demeans the lives of homosexual persons” and therefore would no longer be valid. The ACLU’s amicus brief was cited by Justice Kennedy, who relied on the historical research it provided. He also utilized the arguments put forward by a number of groundbreaking historians of gender and sexuality who carefully charted the trajectories of American cultural and legal norms regarding same-sex intimacy since the nation’s founding.

Fifty years of organizing, agitating, and litigating by LGBTQ people and their allies yielded a significant victory. In particular, the nearly 20 years between Bowers v. Hardwick and Lawrence v. Texas saw tremendous increases in visibility that ranged from small personal acts of bravery, such as coming out as LGBTQ to family, friends, and employers, to candidates running for and winning public office. The decades of the 1980s and 1990s also saw the development and growth of specific areas of LGBTQ scholarship and organizing in educational institutions at all levels, from high schools and community colleges to the most respected universities in the nation.

Attorney Ruth Harlow stands outside U.S. District Court on Thursday, April 25, 2019, in Yakima, WA

Amanda Ray/Yakima Herald-Republic via AP

The Lessons of Lawrence

For LGBTQ activists as well as advocates 16 years ago, the Lawrence victory was enthusiastically celebrated.

“Today the U.S. Supreme Court closed the door on an era of intolerance and ushered in a new era of respect and equal treatment for gay Americans,” said Ruth Harlow, Legal Director at Lambda Legal Defense & Education Fund and lead counsel on the case. (Today, Harlow is Senior Staff Attorney with ACLU’s Reproductive Freedom Project.) “This historic civil rights victory recognizes that love, sexuality, and family play the same role in gay people’s lives as they do for everyone else.”

Coming just as Pride celebrations in major U.S. cities were about to begin, LGBTQ people and their allies gathered in rallies nationwide when the decision was announced on June 26, 2003. When I heard about the Lawrence decision, I immediately called Phyllis Lyon, one of the founders of Daughters of Bilitis, at her home in San Francisco to share the good news. Still active in LGBTQ movements at age 79, she responded, “I never thought I would see this in my lifetime.” Afterward, my partner Ann Cammett and I joined the joyous crowds gathered at the Stonewall Inn in New York to celebrate.

In the years following Lawrence, the ACLU continued to increase its commitments to the cause of LGBT equality. In 2006, an annual update of the LGBT & HIV Project noted that “Six affiliates (Illinois, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, Northern California, and Southern California) have staff and attorneys focused on LGBT rights, and several others have activist member/volunteer groups working on LGBT rights and HIV concerns (Delaware, Eastern Missouri, Kansas and Western Missouri, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Nevada, Southern and Northern California, and Washington).”

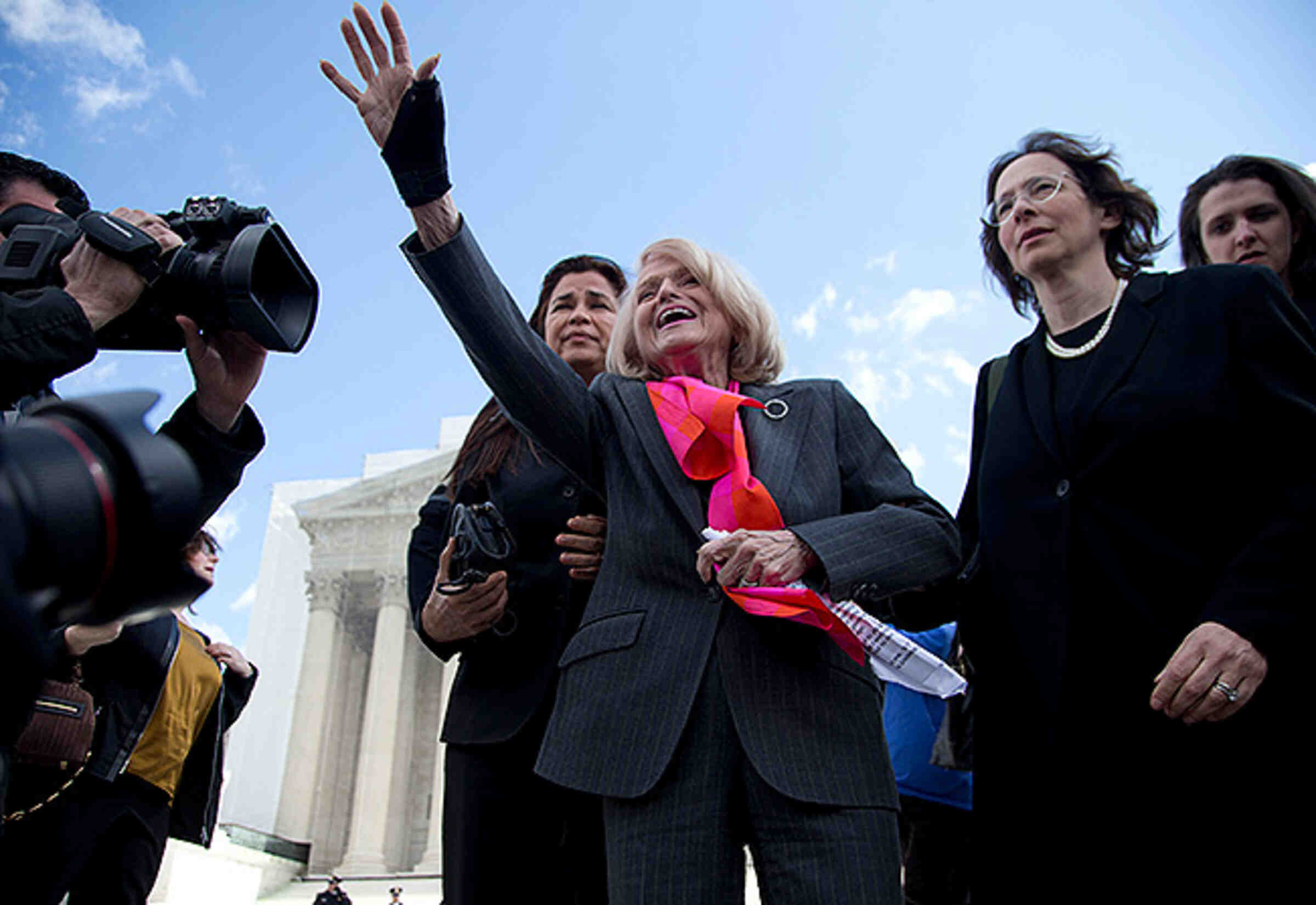

Plaintiff Edith Windsor waves to supporters in front of the Supreme Court in Washington, Wednesday, March 27, 2013, after the court heard arguments on her Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) case.

AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster

Lawrence also provided the basis for subsequent significant SCOTUS decisions in two landmark ACLU cases, U.S. v. Windsor and Obergefell v. Hodges. In the case brought on behalf of New Yorker Edie Windsor, who sought to inherit her spouse’s estate after her death, the Supreme Court, with Justice Kennedy again writing for the majority, ruled that states have the authority to define marital relationships and that the 1996 federal Defense Of Marriage Act, DOMA, went against legislative and historical precedent by undermining that authority. The result, Kennedy wrote in 2013, was a denial to same-sex couples of the rights that come from federal recognition of marriage, which are available to other couples with legal marriages under state law. The court noted that the purpose and effect of DOMA was to impose a "disadvantage, a separate status, and so a stigma" on same-sex couples in violation of the Fifth Amendment's guarantee of equal protection.

Two years later, with Justice Kennedy again writing for the majority, the court ruled for plaintiffs in Obergefell v. Hodges, which challenged Ohio’s refusal to recognize same-sex marriages. On June 26, 2015 — again, just in time for Pride celebrations nationwide — the majority in SCOTUS held that the Fourteenth Amendment requires all states to license marriages between same-sex couples and to recognize all marriages that were lawfully performed out of state.

In this March 6, 2015, photo, James Obergefell speaks to a member of the media. Obergefell was the named plaintiff in Obergefell v. Hodges, a marriage equality case heard by the U.S. Supreme Court on April 28 that year.

AP Photo/Andrew Harnik

“The most important thing was that enough of the country got used to the idea that a same-sex couple's marriage was really a marriage,” wrote law professor Jedediah Purdy in a 2017 essay, “Citizen Activism and the Courts.” “With that done, it was a relatively short step to conclude that constitutional freedom and equality required legal recognition of that marriage.”

In 2019, the continuing existence of state-level protections for LGBTQ+ people — in place in nearly half of the 50 states and the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico — awaited the decision of the Supreme Court in the ACLU cases of Altitude Express Inc. v. Zarda and Bostock v. Clayton County (combined) and R.G. and G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and Aimee Stephens. At issue was whether Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act bans employment discrimination based on sex.

SCOTUS issued its decision on June 15, 2020, deciding 6-3 that Title VII protections against sex discrimination did extend to “gay or transgender” individuals. James Esseks, director of the ACLU’s LGBTQ & HIV Project, noted, “This is a huge victory for LGBTQ equality.” He honored the decades of struggle that had preceded the ruling. “Over 50 years ago, Black and Brown trans women, drag queens, and butch lesbians fought back against police brutality and discrimination that too many LGBTQ people still face. The Supreme Court’s clarification that it’s unlawful to fire people because they’re LGBTQ is the result of decades of advocates fighting for our rights.”

Aimee Stephens, seated center, and her wife Donna Stephens, in pink, listen during a news conference outside the Supreme Court in Washington, Tuesday, Oct. 8, 2019.

ACLU

One of the plaintiffs, Aimee Stephens, died before the court ruled. However, she left a message in which she shared her hopes for the outcome: “Firing me because I’m transgender was discrimination, plain and simple, and I am glad the court recognized what happened to me is wrong and illegal. I am thankful that the court said my transgender siblings and I have a place in our laws.”

However relieved we as LGBTQ people were to be included in federal employment protections that prohibit sex discrimination, our struggle for equal justice continues. Still to be determined in a future SCOTUS ruling is whether employers can utilize their religious beliefs to discriminate against us. Specifically, the Supreme Court in 2020 also granted review in a case, brought by the national ACLU and the ACLU of Pennsyvania, to decide whether taxpayer-funded government-contracted foster care agencies can claim religious beliefs as a basis on which to deny same-sex couples licenses as foster parents (Fulton v. City of Philadelphia).

Also pending, as of this essay’s publication, is the very future of the U.S. Supreme Court itself, following the devastating loss of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg on September 18, 2020. Ginsberg, who co-founded the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project in 1972, had an unwavering commitment to civil rights and civil liberties. Her decades-long fight to end sex-based discrimination enabled legal protections for LGBTQ people. As Executive Director Anthony D. Romero noted in the ACLU’s statement on her passing, “She leaves a country changed because of her life’s work.”

One thing we know for sure in these uncertain times: Through the combined strengths of its members, affiliates, and national staff, the ACLU will be at the forefront of the fight to protect and expand constitutional rights for all.

Author's Note: I am indebted to Matt Coles for documenting in 1999 a history of the ACLU’s work on behalf of LGBTQ peoples and HIV/AIDS in the 20th century: Read "The ACLU Then and Now"

For additional information, see also: The Annual Update of the ACLU's Nationwide Work on LGBT Rights and HIV/AIDS

Marcia M. Gallo is the author of numerous essays and book chapters on LGBTQ and other social movements as well as two prize-winning books: Different Daughters: A History of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Rise of the Lesbian Rights Movement (Carroll & Graf, 2006; Seal Press, 2007) and "No One Helped": Kitty Genovese, New York City, and the Myth of Urban Apathy (Cornell University Press 2015).

She was the Field Director for the ACLU of Northern California from 1981 to 1995. Working with a team of volunteer activists, she mobilized ACLU-NC members, complementing the work of ACLU’s attorneys and lobbyists. She also was the founding director of the Howard A. Friedman First Amendment Education Project, which brought high school students and teachers into active involvement with the ACLU-NC on a variety of issues.

After moving to New York and completing the doctoral program in American history at the City University of New York Graduate Center, she taught at Lehman College in the Bronx, New York before joining the faculty of the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. She retired from UNLV in June 2020 and returned to New York where she continues to write, lecture, and organize.