The following is a Q&A with David Cole, civil liberties litigator, law professor, recipient of the ACLU’s inaugural Norman Dorsen Presidential Prize, and author of the just-published book, “Engines of Liberty: The Power of Citizen Activists to Make Constitutional Law” (Basic Books). The book tracks three campaigns — one relating to marriage equality, another relating to gun rights, and another relating to human rights in the context of the “war on terror” — to examine, as the title suggests, how constitutional law gets made.

Jameel Jaffer: First, congratulations. “Engines of Liberty” is provocative and fascinating, and it supplies a persuasive theory of how constitutional change actually happens. The book's basic thesis is that "associations of committed citizens" are crucial to the development of constitutional law, perhaps "even more important than the courts." This will come as a surprise to many readers, I think. Most people tend to think that constitutional law is made by judges, not by advocates at organizations like the National Rifle Association and the ACLU. Is the central role that advocacy groups play in this context something that citizens should find reassuring, alarming, or neither?

David Cole: Thanks so much, Jameel. I hope readers and citizens will find the book’s message empowering. My principal point is that constitutional law depends on us as citizens, as much or more than it does on judges and formal checks and balances. I try to show that through explaining how marriage equality and the right to bear arms came to be recognized as constitutional rights, and how President Bush was driven to curtail his most egregious counterterror measures in the war on terror. In my account, constitutional law depends on our involvement and engagement as citizens in organizations committed to the constitutional values we care about — groups like the ACLU. As the story of the NRA and the right to bear arms illustrates, citizen engagement does not inevitably lead constitutional law in a liberal or a conservative direction. My point, rather, is that this is where the action is, so if you care, you should get engaged. And the broader, and I hope inspiring, point is that through such engagement, groups of citizens can — and have — succeeded in shaping constitutional law to reflect their deepest commitments.

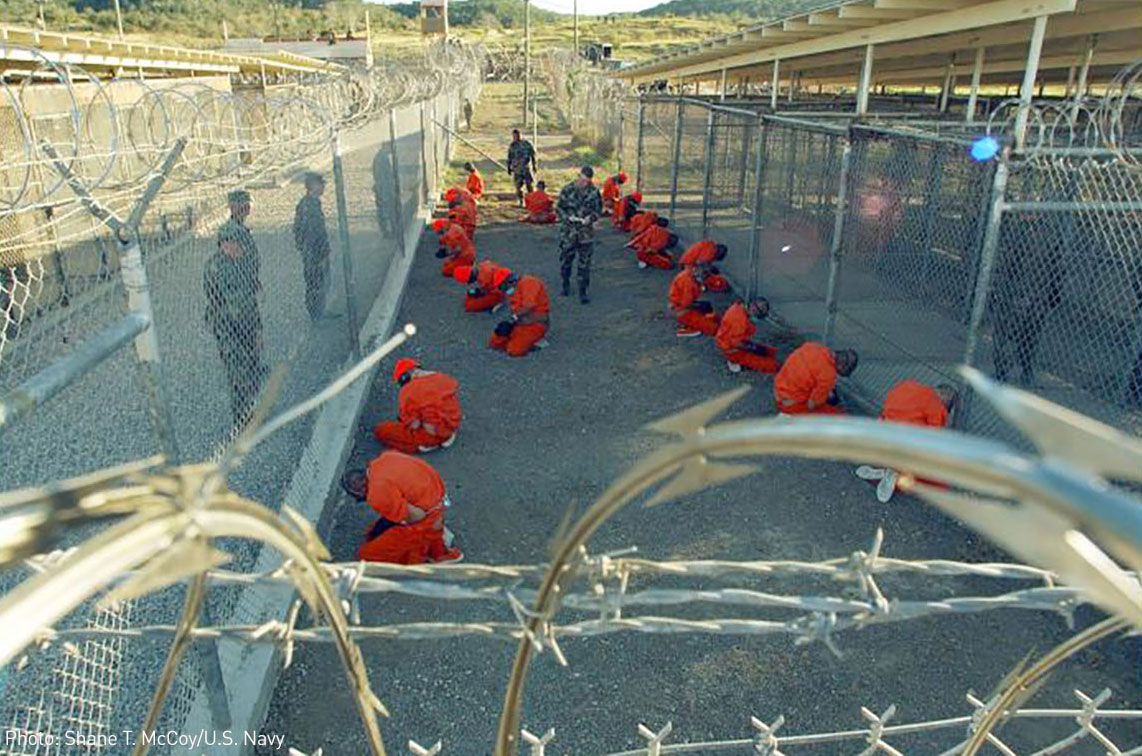

JJ: You trace three different campaigns — one relating to marriage equality, another relating to gun rights, and another relating to civil liberties and national security. It seems to me that one of these is not like the others. The first two can fairly be described as having been successful — even spectacularly so. But while human rights advocates have managed to limit and even end some of the abuses associated with the so-called "war on terror," I don't think there's any denying that the national security state has grown dramatically since 9/11, to the detriment of democratic freedoms and human rights. (To the detriment of security, too, but that's a topic for another day.) Despite the very real successes of organizations like the Center for Constitutional Rights, Reprieve, Human Rights First, and the ACLU, I don't think one can plausibly say that in this particular area the arc of history over the last 20 years has bent towards justice. If you agree with me about that, then what do you think explains the fact that associations of committed citizens have not had the same success in this area as they have in the others?

In other words, civil society mobilization is not a panacea, but it is a critical checking force.

DC: You’re absolutely right that the human rights story is more mixed, and the successes more qualified. That said, I read the evidence more optimistically than you do. I think it’s actually quite something that, by the time George W. Bush left office, he had released over 500 of the Guantánamo detainees, cleared out the Central Intelligence Agency’s secret prisons, suspended the torture program, and brought the National Security Agency’s warrantless wiretapping program under judicial supervision. These are not minor adjustments; and Bush did not adopt them of his own volition, but only because of the pressures created by the advocacy of groups like ACLU, CCR, HRF, and Reprieve, to name just a few of those I portray. But the critical question is not whether you see the glass as half full or half empty, but what would the situation look like without these groups? In other words, civil society mobilization is not a panacea, but it is a critical checking force.

As for why this area has been less successful, I think there are many answers. First, the rights at issue for the most part are those of foreign nationals, and the democratic processes that I argue underlie so much constitutionalism are less likely to work when those whose rights are at issue are not represented. Second, national security crises have always provoked overreaching; we are unlikely to immunize ourselves from that problem. The best we can do is support organizations that work to mitigate and limit the abuses. Third, there is a legitimate and difficult question about where the balance ought to be struck in the post-9/11 era. It is far from obvious, for example, that the balance should be the same as it was before 9/11. The threats are different; the tools the government employs are different; and the balance may need to be different. I don’t think you measure success or failure by whether our society has changed since 9/11.

JJ: Your first section, about the fight for marriage equality, makes such a compelling case for incrementalism — step-by-step change over time, in the service of a larger vision. Do you see other movements deliberately adopting an incrementalist strategy now?

DC: Absolutely. My own sense is that incrementalism is pretty much all there is. The NRA, the gay rights groups, and the human rights groups all succeeded in significant part by acting incrementally. Campaign finance reform today is similarly proceeding incrementally, introducing clean election and public financing and disclosure reforms in the most receptive states first, and then seeking to spread those wins to other states. A full-frontal attack on Citizens United is unlikely to prevail, but attacking it around the edges shows more promise. The same is true with the right-to-life campaign against Roe v. Wade, and, for that matter, the work of those seeking to establish a right to death with dignity. All of these campaigns are engaged in incremental reforms, with their eye toward major constitutional change down the road.

JJ: The movements you profile all had leaders — many of them lawyers from “elite” law schools — with institutional resources behind them. Some of the most vital political movements today — Black Lives Matter is the obvious example — don’t have centralized leadership and don’t have the same kinds of resources behind them. Do you think movements like these will help shape constitutional law?

DC: Constitutional change takes time. People think of the marriage equality campaign as having achieved victory overnight, but as I show, the effort was decades in the making. This reality means that you need institutions with a long view, with the resources, commitment, and staying power to persist over the long term. Movement organizations like Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter undoubtedly play an important role in raising consciousness and sparking popular interest and demands for change. But I suspect that constitutional change will generally require institutions that are more long-lasting. That said, they can be created out of whole cloth. Evan Wolfson created Freedom to Marry in 2003, but it quickly became a multimillion dollar organization. And it did so not because Evan Wolfson himself had resources, but because the idea it sought to advance appealed to people sufficiently to lead them to donate generously to the cause. The money as often as not follows the ideas.

JJ: As someone who has lost more than his share of cases, I appreciate your observation that, in long-term campaigns, losses can be productive because they can focus the public's attention on injustice and galvanize advocates. You also note that legal victories can sometimes backfire. (You discuss, for example, the backlash to Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, in which the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court held in a 4-3 vote that denying marriage to same-sex couples violated the state constitution.) I think you’re right about both of these things — courtroom wins can morph into political losses, and courtroom losses can morph into political wins. I'm wondering, though, what advocates can take away from this. I’m pretty sure you’re not arguing that we should try to win fewer cases and lose more.

DC: Of course not! The key is how to learn from losing and how to defend victories. The marriage equality groups learned the hard way that a victory in court was not sufficient, and that they had to focus on advocacy in the public arena if they were to hold onto their victories in the courts. At the same time, they managed to learn from their losses. In particular, as I show in the book, they wholly reshaped their messaging in referendum campaigns after the loss on California’s Proposition 8, which overturned a California Supreme Court decision recognizing marriage equality. With revamped messaging, three years later, in the 2012 election, they won all four ballot campaigns in which marriage equality was at issue.

JJ: Your juxtaposition of the NRA with organizations like the ACLU is jarring but also illuminating. You focus mainly on what these kinds of organizations have in common. I’m curious, though, about any differences you discovered about the way that the NRA and the ACLU do their work. Obviously, our goals are very different, but are there lessons you think the ACLU can learn from the experience and strategies of the NRA?

DC: One of the lessons I came away with was that we can all learn from the NRA. Whether you agree with it substantively or not, it has been an incredibly effective organization. It has certain advantages, no doubt, principally its 5 million members and the many millions more who support it and identify with it. But I think we could all learn from their emphasis on building a sense of identity and community among members, from their laser-like focus, and from their deep understanding that the protection of a constitutional right starts with electoral politics. Their engagement in elections is, in my view, a key to their success in defending the right to bear arms.

JJ: Let me come back to national security. As you note in your book, civil liberties and human rights groups successfully challenged the first iteration of the military commissions at Guantánamo, the warrantless wiretapping program, and the denial of habeas corpus rights to prisoners held at Guantánamo. As a result, the government’s policies changed in important ways. But one result of the legal challenges — and this is something that Jack Goldsmith points out (and applauds) in his book, “Power and Constraint” — is that the government’s current national security policies, including policies that are still profoundly problematic from a civil liberties and human rights perspective, are now arguably on stronger legal footing. How does this factor into your assessment of the extent to which human rights advocates have been “successful” in this context? Does it matter that narrowing some of the government’s policies — and ending some abuses — meant legitimating a narrowed but still deeply problematic version of those policies?

DC: Great question, and probably deeply unanswerable. My own sense is that it is a good thing that torture is not being practiced, that most of the Guantánamo detainees have been released, that the CIA is not disappearing suspects into secret prisons, and that the NSA’s programs are subject to judicial supervision. Of course, it is true that the fact that civil society groups helped to end some egregious abuses means that the practices that remain are more legitimate and more difficult to challenge, but that is always the case. Ending formal segregation made it harder to challenge de facto segregation. Ending explicit racism makes it harder to challenge unconscious racism. But I don’t think that means that the NAACP LDF should not have challenged Jim Crow segregation, or that CCR and ACLU should not have challenged torture, disappearances, and warrantless wiretapping. A group committed to constitutional rights has to challenge rights violations when they arise. The fact that the ACLU has not succeeded in creating the world its members envision in whole just means the work must continue.

JJ: You dedicate your book to Michael Ratner, who led the Center for Constitutional Rights for many years and who has been — and continues to be — a truly inspiring figure to many human rights advocates, including to me. In your dedication, you write that Michael taught you “that the struggle for justice is always worthwhile, even and especially where it appears most hopeless, and that occasionally, justice prevails over hopelessness.” Your book has that same hopeful spirit — and with presidential candidates enthusiastically advocating torture and discrimination, it’s refreshing to read a book that is so optimistic about our constitutional future, or at least about our ability to shape our constitutional future. But you must have submitted this book to your publisher several months ago. Have events since then compelled you to reconsider your optimism?

DC: Another great question. As to the presidential politics of the present moment, I’m confident that the American people in a general election will reject candidates who have expressed support for extreme abuses of civil liberties and human rights. There is a big difference between primary and general election politics. I could be proved wrong, of course. But even then, my view will be that such an outcome would only make the work of groups like the ACLU all the more essential. I end my book with a quotation from Cornel West and Roberto Unger, and it’s one that has guided me throughout my career. They write that “hope is more the consequence of action than its cause. As the experience of the spectator favors fatalism, so the experience of the agent produces hope.” This is a book about agents of hope, not fatalistic spectators. I’ve seen what agents can do — indeed what you at the ACLU can do — and it’s precisely that which gives me hope.

David Cole's "Engines of Liberty" is available here.