Separate Is Never Equal: A Lesson in Civil Rights from the D.C. (Anti-) Prop 8 Rally

Alright, I admit it. I am one of those ACLU staffers who works on national security issues and didn't understand why, when the government is spying on innocent Americans or torturing people, I should focus on the rights of a few to marry, even if the issue affects some of my closest friends — or even me. Until election night. I had just returned from watching returns and was excited that it seemed that America had gotten over enough racial bias to elect a black man, who was born before the Civil Rights Act passed or the Voting Rights Act guaranteed the rights of African-Americans to vote, to the presidency. I opened my laptop to check the results of the California Proposition 8 Ballot Measure and felt like someone had punched me in the gut. I had thought that the U.S. had overcome so much prejudice in this election, but here was California, a supposed progressive bastion, voting to deny equal rights to a certain minority.

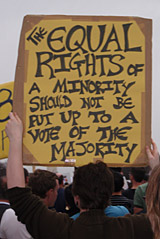

This past Saturday, I attended the D.C. (Anti-)Proposition 8 Rally (or, as we rally-ers un-affectionately called it, H8 — pronounced "hate") and was inspired by the various signs spanning the full spectrum of angles on marriage for same-sex couples. Signs proclaimed everything from "The Equal Rights of a Minority Should Not Be Put Up To a Vote of the Majority" to "Marriage is About Love Not Hate" and "H8 is Not a Family Value." High school kids marched alongside middle-aged couples (straight and gay), and one family brought signs that read "How Does Protecting Our Family Hurt Your Family?" From the marshals to the speakers to the marchers, a rainbow of faces and personalities matched the rainbow flags that some of the participants were carrying. Perhaps the sign that summed up the spirit of the day was the one that read "It's about Love and Equality."

After the rally, I found an article by University of Pennsylvania Law Professor Kermit Roosevelt asking when a majority should have the power to take away a constitutional right granted by a court. He reminds us that nationally, a two-thirds — or a "super" — majority is required to amend the Constitution, unlike in California where a simple 52-47 vote outlawed gay marriage. Roosevelt explains the super-majority requirement saying:

At one point in time, a particular [discriminatory] practice . . . is so widely accepted that it seems beyond challenge. Judges are not likely to strike the practice down, and if they did, the backlash might well be strong enough to create a constitutional amendment.

Some time later, the practice becomes controversial. It still enjoys majority support — otherwise it would likely be undone through ordinary lawmaking — but it no longer has the allegiance of a supermajority. It is at this time that judges tend to act in order to protect the freedoms of the minority, striking down the practice as unjustified discrimination. The decision may be intensely controversial. It may even be the target of majority disapproval. But because there is no longer a supermajority, the decision is safe.

As attitudes evolve, the [discriminatory] practice comes to seem outrageous . . . At this point, the judicial decision is no longer controversial.

If a majority could overrule a judicial decision, the process would frequently be stopped by that majority vote. Judicial interventions against discrimination would just not succeed.

Already at the rally, I could feel this evolution of public opinion in process. As rain poured down on the thousands of us marching on the Mall in Washington and people began dancing in the mud, the cars passing by honked their support and passersby snapped photos and gave us thumbs up. As over a million people marched in similar protests in 300 U.S. cities in all 50 states and in 10 countries around the globe, it was clear that marriage for same-sex couples is becoming less and less controversial and that discomfort with a simple majority vote to deny the right to marry is rising. After all, as Professor Roosevelt points out, "[M]ost of us are at some point in a minority. All of us could be affected."

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.