This piece was originally posted on the Huffington Post.

This is the story of two couples; two couples who come out of the same post-war generation, and who built their lives around the same emotional core of love, commitment, and devotion to one another. And yet, their relationships were marked very differently by history and by the laws that governed their lives.

Both relationships begin with a dance.

To hear my father tell it, my mother first caught his eye as she ran to catch the morning commuter train out of Rockville Center. She would be wearing a chartreuse raincoat and would be rushing off, as he would later learn, to her secretarial job in Manhattan. They would eventually meet at a St. Patrick's Day dance at a nearby Catholic church. Six months later, in the fall of 1947, they were married.

When Edie Windsor tells the story of her life with Thea Spyer, she always begins with a dance. It was 1963, at a restaurant in Greenwich Village where Thea first caught Edie's eye. Dancing followed dinner, and they danced until Edie wore a hole in her stocking. After that first night, they would look for as many opportunities as possible to dance with one another. Four years later, they moved in together. And while marriage was not an option for two women in 1967, they knew that they wanted to spend the rest of their lives together. To avoid unwelcome scrutiny, when Thea proposed to Edie with a diamond brooch, they only shared the news with a small circle of trusted friends. And thus began their very long engagement.

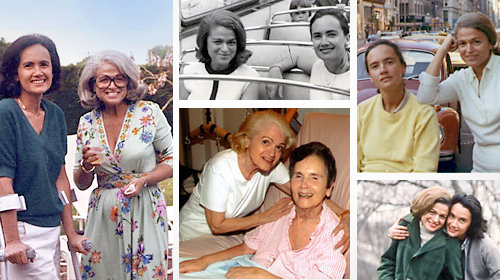

In many ways, my parents and Edie and Thea lived parallel lives. My parents eventually settled on the North Shore of Eastern Long Island, buying a two-story colonial and raising four children. They had a storybook marriage, almost literally something out of an Ozzie and Harriet script. My dad was a banker and my mom was a stay-at-home mother. As children of the Depression, they focused on securing our future. They worked to ensure that we had what we needed, and they saved so that we could go to college and they could retire without becoming a burden to their children. Most of all, they taught us the value of hard work and of treating others the way you would want to be treated. For my father, in particular, treating people fairly was a guiding principle.

I now know that one of the most remarkable things about my parents was their marriage and the bond that they so clearly shared. It was a gentle and respectful bond. Every night, when my father got home from the office, they would sit down together at the kitchen table and talk about their respective days. I was not interested in their conversation at the time, but I did count on seeing them together at the table, punctuating our day with their companionship.

I see that same enduring companionship in Edie and Thea's life. Edie was a successful computer programmer at IBM, and Thea -- Dr. Spyer -- was a clinical psychologist with an active private practice. They worked hard, paid taxes, traveled the world together, and entertained friends in their Manhattan apartment and their modest summer home in the Hamptons. Granted their lives were perhaps more glamorous than that of my suburban family's in the 1960s and 70s, but like my parents, they were there for each other at the beginning and the end of each day. They shared their joys, their challenges, and their sorrows. To this day, four years after Thea's death, Thea is the first person Edie wants to talk to when something ordinary or extraordinary happens in her life. I am quite certain that my mother -- six years after my father's death -- knows exactly how Edie feels.

And here again, I see my mother and Edie, despite their obvious differences, sharing a very important life thread. Both stood by as the love of their life struggled through a debilitating illness. For my parents, it was Alzheimer's. For Edie and Thea, it was multiple sclerosis (MS).

In 1977, Thea was diagnosed with MS which gradually caused progressive paralysis. For decades, Edie helped Thea manage as she went from using a cane, to crutches, to a manual wheelchair, to a motorized wheelchair that she could operate with her one working finger. According to Edie, it was like MS happened to both of them. It gradually changed their lives, but they faced Thea's illness together. MS eventually limited their options, but it never stopped them from dancing or diminished the love and admiration they had for one another.

As Thea's condition worsened, Edie would periodically ask Thea if she wanted to finally get married. Though getting married would have fulfilled their lifelong dream, Thea wasn't sure she had the physical stamina to see that dream become a reality. But when it became clear that she would not likely live more than a year, she faced her prognosis by once again proposing to Edie: "Do you still want to get married?" Edie joyfully replied, "Yes!"

But it was 2007 and they could not yet marry in New York as they had always planned. Instead, joined by a physician and several close friends, they flew to Toronto, where they were married on May 22, 2007.

Edie and Thea spent the next two years happily married in spite of the toll that MS and Thea's developing heart condition was taking on them. Edie will tell you, "It was a love affair that just kept on and on and on," even as Thea's condition got profoundly graver. Thea would ask Edie, "I'm dying, aren't I?" Edie would gently comfort her, "We're both dying honey. We're old ladies after all." They were old ladies who had spent more than 40 years loving and caring for each other. Now was no different: Three weeks before Thea Spyer died, she turned to Edie and said, "Jesus, we're still in love aren't we?" And they were.

For my parents, after more than 50 years of marriage, my father started to show signs that something was not quite right. First little things, like words forgotten, then bigger things like not knowing how to put toothpaste on a toothbrush, or lying in bed late at night and imploring my mother to take him home; they were of course home already. For years, my mother cared for him. For too long, she shielded us from what was really going on. But eventually the disease progressed to a point where even my tough- as-nails mother could no longer care for him at home. My father spent the last two years of his life in a Veteran's home, confined to a wheelchair, and gradually losing the ability to do anything on his own. My then-80 year old mother would visit him and spend every day by his side. Though he could no longer communicate with us, it was clear that he knew somehow that he belonged to us and even the Alzheimer's could not erase the years of companionship my parents had shared. Their love had left an indelible mark on their hearts. Two days before my father took his last breath, my mother leaned over and kissed him goodbye for the evening as she always did. "I love you, Jim." He reflexively kissed her back, and then, looked at her and said, "I love you too, Mary." Those were his last words.

At roughly the same time, Edie and my mother had to face their lives without their respective spouses, the people they had shared every aspect of their lives with for decades. Soon after Thea's death, grief-stricken, Edie suffered a severe heart attack and received a diagnosis of stress cardiomyopathy, or "broken heart syndrome." My mother's broken heart did not manifest itself in sickness, but her sadness was palpable for months. Gradually, with her grandchildren and children circling around her, she found a way out of her grief. And while she still misses my father tremendously, she has found joy again in her life.

For Edie, the road has been harder, due in large part because of a legal system that treats same-sex couples like Edie and Thea very differently from how it treats heterosexual couples like my parents. When Thea died, she left all of her possessions to Edie, but because of the Defense of Marriage Act (also known as DOMA), Edie was forced to pay more than $360,000 in federal estate taxes. When my father died, he too left all his possessions to my mother, and though there was certainly a mountain of paperwork to wade through, my mother did not owe the federal government a dime.

When it came to these two marriages both built on love, commitment, and devotion, because of DOMA, our federal government failed to treat them equally. Until 1996, federal law contained no comprehensive definition of the words "marriage" or "spouse." DOMA changed this by restricting the definition of marriage to "only a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife." For all intents and purposes, DOMA designated Edie and Thea strangers, burdening Edie with an enormous tax bill on top of her grief.

My father and I never talked about marriage for same-sex couples, but I know that he would have understood the shameful lack of fairness that DOMA enshrines.

Edie found a way out of her grief by standing up to the injustice of DOMA. In 2010, she challenged the constitutionality of DOMA in federal court. In March, Edie brought her case before the nine Justices of the U.S. Supreme Court, which will issue a decision by the end of June. As the Justices consider Edie's challenge, I hope that they can see Edie and Thea's marriage for what it truly was: a love story for the ages, and that they will duly honor that love by finally overturning this unjust law.

Learn more about same-sex marriage and other civil liberty issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.