Today the ACLU filed a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit to force the government to release statistics about its use of powerful electronic surveillance tools that law enforcement can use against any American simply by stating to a judge that it’s relevant to an investigation. The Department of Justice is required to disclose these statistics to Congress each year, yet routinely fails to do so. Today’s suit is an effort to compel the DOJ to follow the law (here are our complaint and our FOIA request).

The surveillance tools at issue are called pen registers and trap and trace devices. Originally these devices were designed to eavesdrop on the old analog telephone network, but now they refer to a broader type of electronic eavesdropping. Using these methods, the Justice Department has claimed the authority to reveal:

• The phone numbers you call and that call you

• The time each call is made

• The length of each call

• The email addresses of the people you send emails to and who email you

• Your IP address and the IP addresses of computers you connect with (IP addresses can reveal physical location)

• The web addresses of the websites you visit

The Supreme Court decided in 1979 that pen registers and trap and trace devices were not covered by the Fourth Amendment because the “non-content information” the police monitored, like the numbers the caller dialed, were “voluntarily disclosed” to the telephone company. But Congress was not entirely comfortable with such a carte blanche granted to the executive branch, and so in 1986 it passed the Pen Register Act, which laid out restrictions that were, though minimal, intended to provide oversight on law enforcement’s use of these invasive surveillance methods.

To initiate a pen register or trap and trace device under the act, law enforcement can simply file a certification with a court stating that the information they are likely to obtain is “relevant to an ongoing criminal investigation.” In other words, the Pen Register Act does not authorize judges to weigh the substantive merits of an officer’s request. If officers fulfill the procedural requirements by submitting the certification, judges have no leeway to deny these orders.

Given the merely procedural process set for law enforcement agents, the act requires the attorney general to submit a report to Congress every year cataloguing each order and describing how the surveillance power was used. As Senator Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) explained when sponsoring a successful bill to expand these requirements, “adequate oversight of the surveillance activities of federal law enforcement [can] only be accomplished with reporting requirements.” Senator Leahy also explained that the purpose of the attorney general’s annual report is to inform both “Congress and the public.”

As such, the attorney general is required by law to submit annually a report that lists:

(1) The period of interceptions authorized by each order and the number and duration of any extensions of each order

(2) The specific offenses for which each order was granted

(3) The total number of investigations that involved orders

(4) The total number of facilities (like phones) affected

(5) The district applying for and the person authorizing each order

The reporting requirements aren’t perfect. One of their biggest flaws is that they only cover law enforcement agencies within the Department of Justice. They don’t apply to the Department of Homeland Security at all, and so agencies within that department, such as the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, don’t have to report anything. They also don’t cover state and local authorities, who can engage in the same types of surveillance. But the reporting requirements are better than nothing, and they are the best insight we have into how the federal government uses these powerful surveillance tools.

Unfortunately, as we have learned through FOIA requests by interested privacy advocates, the Justice Department has a record of failing to meet its legal obligations to report the use of pen registers and trap and trace devices to Congress.

• For each year from 1999 to 2003, the DOJ failed to submit any data to Congress. They finally sent a package of delinquent data in a single “document dump” in 2004.

• Another data blackout occurred between 2004 and 2009, when the DOJ again sent four years of delinquent data to Congress.

• In 2010 and 2011, the DOJ has failed to make public data and reports on its usage of pen registers and trap and trace devices, putting privacy advocates square in the middle of a similar data blackout.

It is no surprise that in his analysis of the situation, scholar Paul Schwartz concludes that DOJ reporting failures have created “blank spaces on the map of telecommunications surveillance law."

Without current data on the government’s use of warrantless and invasive searches into Americans’ private lives, we are once again left in the dark. This is a problem for two reasons. First, government transparency is of vital importance in a democracy. As the president emphasizes on the White House website, “Government should be transparent. Transparency promotes accountability and provides information for citizens about what their Government is doing.” The information we’re seeking is important because in order to have meaningful debate over government surveillance powers, we must be able to answer basic questions about the government’s current use of such powers.

But of more immediate concern, by subverting its legal obligation the DOJ has managed to completely escape the only oversight that Congress established on a very invasive surveillance power. Like a fire alarm, oversight mechanisms signal to Congress when the executive branch drastically expands its surveillance activities or oversteps the boundaries of its authority. Oversight also discourages executive agencies from taking such steps. Government overreach therefore becomes particularly worrisome when oversight mechanisms are not properly carried out.

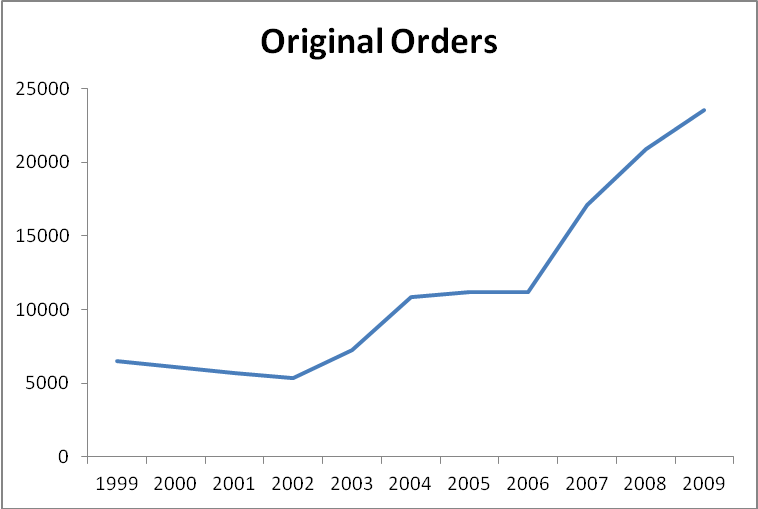

During the last decade’s data blackouts, privacy advocates feared that the use of pen registers and trap and trace devices had become much more frequent, but they had no data with which to properly assess the situation. FOIA litigation by Chris Soghoian in 2010 uncovered data confirming these suspicions. From 2006 to 2009, while the DOJ evaded Congressional oversight, it also radically and suddenly increased the annual number of orders for pen registers and trap and trace devices. As the chart below shows, the annual number of original orders for pen registers and trap and trace devices doubled between 2006 and 2009 from 11,000 to 24,000 (though the government may have sought numerous extensions on those original orders).

As we sit in the midst of another data blackout, we don’t know how severely these numbers may have changed in 2010 and 2011.

The lawsuit we filed today is an effort to end this data blackout. In February of this year, we filed a request for this data under FOIA. Although the government was obligated to respond within 20 days, it is now over two months later and we have yet to receive a complete response. So, we have filed suit. Our legal complaint seeks release of the data and reports from 2010 and 2011 on the federal government’s use of pen registers and trap and trace devices. It also seeks any documents shedding light on any failures to submit those data and reports to Congress.

It is our hope that the DOJ will immediately produce its data from 2010 and 2011 and will make greater efforts in the future to follow the law and report its use of these invasive surveillance techniques to Congress.