Curious Cop Downloaded Hundreds of Private Prescription Records Because He Could

Today, the ACLU and ACLU of Utah filed an amicus brief in support of a Utah paramedic whose Fourth Amendment rights were violated when police swept up his confidential prescription records in a dragnet search. Law enforcement’s disregard for basic legal protections in the case is shocking.

The United Fire Authority (UFA) is Utah’s largest fire agency, with 26 fire stations in communities surrounding Salt Lake City. Last year, some UFA employees discovered that several vials of morphine in ambulances based at three fire stations had been emptied of medication. Suspecting theft, they called the police. At this point, one would expect police to interview firefighters and paramedics with access to ambulances at those three stations and try to draw up a reasonable list of suspects. But one detective had a different idea.

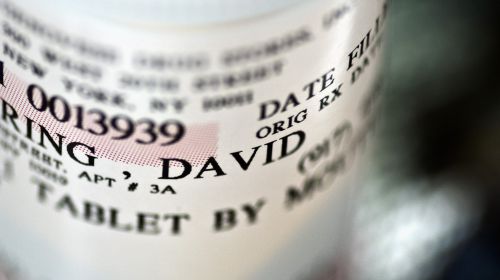

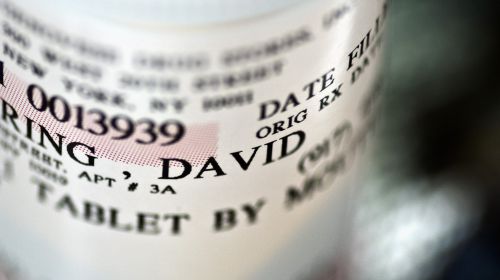

Within a day or two of receiving the theft report, a detective with the Cottonwood Heights Police Department logged into the Utah Controlled Substances Database and downloaded the prescription histories of all 480 UFA employees. The database tracks patients’ prescriptions for medications used to treat a long list of common medical conditions, and the records can reveal extremely sensitive health information. But unlike some other states, Utah doesn’t require police to get a warrant before accessing this private data. The detective took advantage of this loophole and obtained a great deal of confidential information without going to a judge or demonstrating any individualized suspicion.

Even after scooping up the prescription histories of every UFA employee, the detective still couldn’t figure out who might be behind the morphine theft. Instead of stopping there, however, he went on a new fishing expedition through the records, looking for anything he deemed suspicious. He read through the prescription histories of hundreds of firefighters, paramedics, and clerical staff, learning what medications they took and revealing private facts like whether they suffered from an anxiety disorder, chronic pain, insomnia, or AIDS. He identified four people whose records seemed to indicate dependency on opioid painkillers, and convinced a prosecutor to charge three of them with prescription fraud. One of them, paramedic Ryan Pyle, filed a motion to suppress, arguing that the warrantless search of his prescription records violated his Fourth Amendment rights. The ACLU is now weighing in on his side.

Under the Fourth Amendment, police must get a warrant before searching items or places in which people have a reasonable expectation of privacy. The ACLU recently won a case in federal court in Oregon where we sued the federal Drug Enforcement Administration for requesting records from Oregon’s prescription database using administrative subpoenas instead of warrants. As the judge in that case explained, “The court easily concludes that [patients’] subjective expectation of privacy in their prescription information is objectively reasonable. ... The prescription information maintained by [the Oregon database] is intensely private as it connects a person’s identifying information with the prescription drugs they use.”

The Utah detective failed to get a warrant, and therefore violated the Fourth Amendment. As the ACLU’s brief explains, that means the court should throw out the evidence illegally gathered by police. If the Fourth Amendment means anything, it means that police cannot have free rein to flagrantly violate our medical privacy rights without judicial oversight or probable cause.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.