More than a decade ago, a man named Nick Merrill approached the NYCLU and ACLU with an unusual request for help. At the time, Nick ran a small Internet access and consulting business, called Calyx, in New York City.

A few days earlier, an FBI agent had come by Calyx’s offices and handed Nick a “national security letter” demanding that Calyx turn over sensitive information about one of its subscribers. The letter included a gag order prohibiting Calyx from disclosing to anyone that it had received the demand. It also included an attachment listing the kinds of information that the FBI wanted Calyx to turn over.

Nick wasn’t sure why the FBI was demanding the information, but he knew a little about the subscriber the FBI was apparently investigating, and he doubted that the investigation was a legitimate one. He wondered how it was possible that the FBI could demand such sensitive information without the involvement of any judge. And he wondered whether he was violating the gag order simply by asking us for advice.

We didn’t immediately know the answers to Nick’s questions, because we hadn’t seen NSLs before, either. They’d been around for many years, but before 2001 they’d been used sparingly. In October 2001, though, President George W. Bush signed the USA Patriot Act into law, and among many changes the Act made to the surveillance laws were changes that dramatically expanded the FBI’s authority to issue NSLs.

One of the first cases I litigated at the ACLU involved a request under the Freedom of Information Act for information about the FBI’s use of NSLs. Among the documents we received in the course of that litigation was this list of NSLs issued by the FBI between October 2001 and January 2003:

We didn’t realize it at the time, but this heavily redacted document showed an inflection point in the FBI’s use of the NSL power. Behind a veil of secrecy, and relying on changes made by the Patriot Act, the FBI began issuing hundreds of NSLs demanding credit reports, banking information, or records relating to Internet activity. Some of the NSLs sought information about terrorism suspects, but most sought information about people who were one, two, three, or more degrees removed from anyone suspected of having done anything wrong. According to the Justice Department’s inspector general, the FBI issued a staggering 143,074 NSLs between 2003 and 2005. And every NSL was accompanied by a categorical and permanent gag order.

We ended up representing Nick in a challenge to the constitutionality of the NSL statute. The challenge was in many respects successful. The district court struck down the statute in its entirety in 2004, and Congress responded by amending the statute a year later. After we argued that Congress hadn’t addressed all of the statute’s constitutional deficiencies, the district court struck down the statute again. In 2008, the Second Circuit affirmed most of that decision, invalidating some parts of the gag-order scheme and construing other parts of that scheme narrowly.

But throughout the litigation, the gag order prevented Nick from disclosing that the FBI had demanded information from Calyx and from explaining his concerns about the FBI’s investigation. It also prevented him from publicly identifying himself as the recipient of an NSL. In 2007, Nick wrote an anonymous op-ed for the Washington Post discussing some of his frustrations:

I found it particularly difficult to be silent about my concerns while Congress was debating the reauthorization of the Patriot Act in 2005 and early 2006. If I hadn't been under a gag order, I would have contacted members of Congress to discuss my experiences and to advocate changes in the law. The inspector general's report confirms that Congress lacked a complete picture of the problem during a critical time: Even though the NSL statute requires the director of the FBI to fully inform members of the House and Senate about all requests issued under the statute, the FBI significantly underrepresented the number of NSL requests in 2003, 2004 and 2005, according to the report.

I recognize that there may sometimes be a need for secrecy in certain national security investigations. But I've now been under a broad gag order for three years, and other NSL recipients have been silenced for even longer. At some point -- a point we passed long ago -- the secrecy itself becomes a threat to our democracy.

And the gag order remained in place even after Nick had persuaded Congress and the courts to narrow the NSL statute. It wasn’t until 2010 — six years after the gag order was imposed — that Nick was permitted to identify himself as the recipient of an NSL. Even then, the FBI insisted that Nick not disclose the attachment that listed the kinds of records the FBI had demanded Calyx turn over.

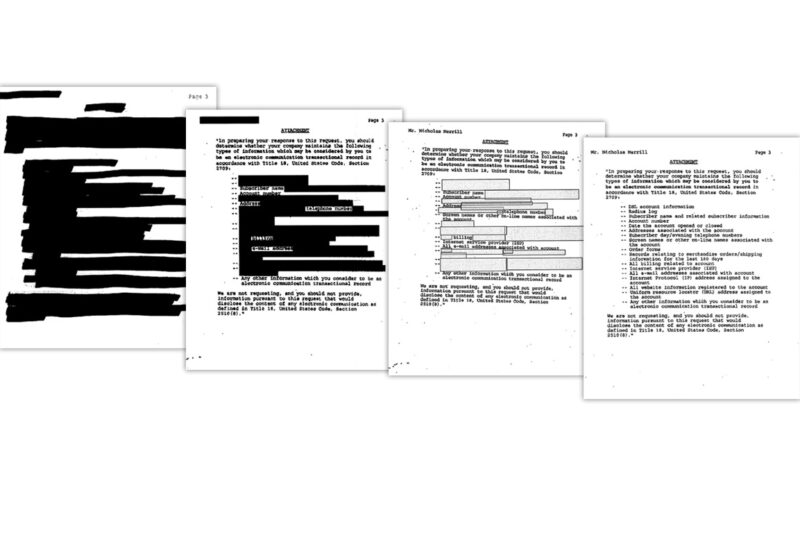

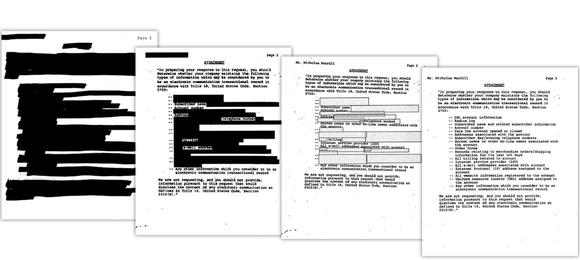

Now, more than 11 years after the order was imposed, the district court has lifted the gag order in its entirety. (The court’s decision was issued a month ago, but for procedural reasons the gag order was not lifted until today.) Thanks to the work of Dave Schulz, Jonathan Manes, Amanda Lynch, Lulu Pantin, and Rebecca Wexler at the Yale Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic, which has represented Nick now for several years, Nick can finally talk freely. He can also disclose the NSL attachment listing the categories of records the FBI demanded.

I am sure that Nick will have lots to say about his experience now that he won’t be prosecuted for saying it. But as government officials once again press for more surveillance powers, it is worth remembering that, as Nick wrote in his 2007 op-ed, there’s still a lot we don’t know about how existing surveillance powers are being used.

As the ACLU acknowledged in Nick’s case, time-limited and narrowly cabined gag orders may be justified in truly extraordinary cases. But the FBI has imposed effectively permanent gag orders on tens of thousands of NSL recipients. It has withheld crucial documents about the use of other surveillance authorities. And it has abused the state-secrets privilege to prevent courts from considering whether intrusive surveillance authorities are lawful.

This kind of secrecy prevents the public from learning how the government’s surveillance authorities are used, distorts public debate, shields policymakers from accountability for their decisions, and insulates surveillance powers from judicial review.

As Nick observed in 2007, we’ve long passed the point at which this secrecy became a threat to our democracy.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.