Monday morning, a federal appeals court released a government memorandum, dated July 16, 2010, authorizing both the Department of Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency to kill Anwar al-Aulaqi, a U.S. citizen, in Yemen.

The publication of the Office of Legal Counsel memo comes, as the court noted, after a lengthy delay. The ACLU (along with the New York Times) has been fighting for this memo since we first asked for it in a Freedom of Information Act request submitted in October 2011.

Monday's release by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit is an important victory for transparency. But while the memo advances the public record in significant ways, it still does not answer many key questions about the government's claimed authority to kill U.S. citizens outside of active battlefields. Here are several important takeaways from Monday's release.

- Rather than more fully explain the government's theory of "imminence," the newly released memo fails to address it at all.

The previously disclosed "White Paper" on the targeted killing of U.S. citizens explained the government's view that "the condition that an operational leader present an 'imminent' threat of violent attack against the United States does not require the United States to have clear evidence that a specific attack on U.S. persons and interests will take place in the immediate future." But rather than give further explanation and clarity to that extraordinary and novel reading of "imminence," the newly released memo — at least as presently redacted — fails to address that requirement in any detail whatsoever.

The memo, signed by David Barron, then–acting chief of the OLC (and now a newly confirmed First Circuit judge), tells us that "[h]igh-level government officials" determined that al-Aulaqi constituted an "imminent" threat to the United States. But the memo does not explain how the government interprets that requirement, nor does the memo explain the evidentiary standard the officials must meet in order to satisfy it.

- Likewise, the memo does not address the circumstances that would make "capture infeasible," and killing therefore permissible:

Again, the White Paper summarized the government's theory about the infeasibility of capture, but the newly released memo adds nothing of substance to that analysis. Importantly, though, the new memo does seem to indicate that its authorization for the targeted killing of al-Aulaqi was intended to be indefinite in duration, requiring only that the CIA and DOD continue to evaluate (without returning to the OLC) "whether changed circumstances" would make capture more feasible.

- "Under the facts represented to us . . ." & why judicial review matters

Throughout the memo, Barron conditions important legal conclusions on "the facts represented to" the OLC by other departments of the executive branch. The memo's discussion of these facts is redacted, making it impossible for the public to evaluate whether the killing of al-Aulaqi meets even the government's professed legal standard. Beyond that absence, however, the memo's repeated conditioning of its conclusions on the version of facts presented by the executive branch makes clear why the government's rejection of any judicial review in this context — either before or after the fact — is so fundamentally dangerous.

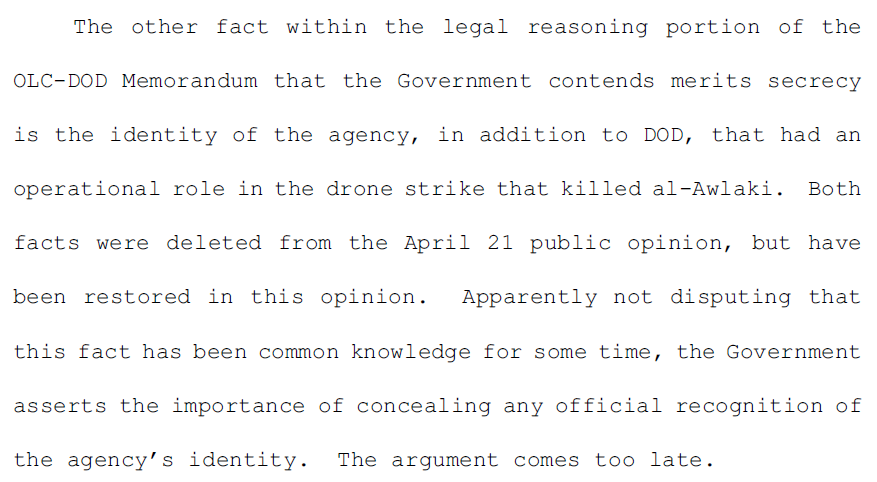

- The CIA — officially — has an operational role in the targeted killing program. From the court opinion released with the memo:

(See the opinion in full, with previously redacted passages highlighted, here.)

Until Monday, the government had argued that the CIA's operational involvement in the targeted killing program was an official secret. In this case and in another ACLU FOIA case seeking documents about the program, the official unveiling of this fact should open the door to further disclosures about the CIA's role in the program and about factual information, like numbers of civilian casualties caused by the program, that the government continues to maintain cannot be disclosed to the public.

- There are additional OLC memos addressing the lawfulness and constitutionality of the targeted killing of U.S. citizens — and the government will likely have to release portions of those as well.

Together, Monday's release and the Second Circuit's opinion make clear that the public is only just starting to understand the legal and factual basis for the government's targeted killing program, as a great deal of information crucial to the public debate remains secret. While we will continue to press for additional disclosures in court, the government need not and should not wait for yet another court order before it discloses additional information to which the public is entitled. In the meantime, stay tuned for further analysis from the ACLU about the meaning of this release as well as what comes next.

Learn more about drones and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.