Today the ACLU publicly supported a document that we believe will prove to be an important step forward in providing privacy transparency for mobile applications. After more than a year of negotiation among industry, trade associations and consumer organizations under the leadership of the Department of Commerce, we have all agreed to move to the testing phase of a model code to provide consistent, easy-to-understand notification when using a mobile app.

The goal of this code is to leverage competition among apps. Consumers can often load many different types of apps that serve the same purpose—weather forecasts, news clips, games and many more. We believe that privacy can and should be one of the key criteria consumers use for making these determinations.

This code takes advantage of this new competitive dynamic by providing key information in a standardized format so that consumers can compare the privacy practices of different apps at a glance. Specifically, signatories to the code will disclose any information they collect in the following eight areas:

- Biometrics (information about your body, including fingerprints, facial recognition, signatures and/or voice print.)

- Browser History (a list of websites visited)

- Phone or Text Log (a list of the calls or texts made or received.)

- Contacts (including list of contacts, social networking connections or their phone numbers, postal, email and text addresses)

- Financial Info (includes credit, bank and consumer-specific financial information such as transaction data.)

- Health, Medical or Therapy Info (including health claims and information used to measure health or wellness.)

- Location (precise past or current location and history of where a user has gone.)

- User Files (files stored on the device that contain your content, such as calendar, photos, text, or video.)

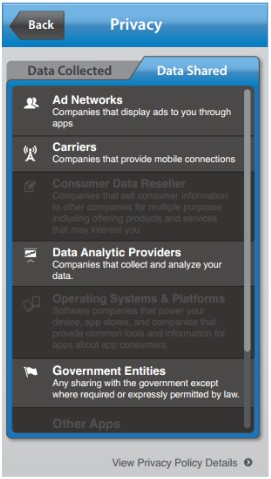

They’ll also disclose whether they share it with any of the following eight entities:

- Ad Networks (Companies that display ads to you through apps.)

- Carriers (Companies that provide mobile connections.)

- Consumer Data Resellers (Companies that sell consumer information to other companies for multiple purposes including offering products and services that may interest you.)

- Data Analytics Providers (Companies that collect and analyze your data.)

- Government Entities (Any sharing with the government except where required by law or expressly permitted in an emergency.)

- Operating Systems and Platforms (Software companies that power your device, app stores, and companies that provide common tools and information for apps about app consumers.)

- Other Apps (Other apps of companies that the consumer may not have a relationship with.)

- Social Networks (Companies that connect individuals around common interests and facilitate sharing.)

To see how this might work in practice, you can see more model screens here.

This list obviously doesn’t cover everything an app can collect or everyone it can share with—but we hope it represents the areas that matter most to consumers. One of the problems with current disclosures is that apps don’t want to appear deceptive so they list everything they might collect, ever. This makes it hard for consumers to zero in on the information that is really relevant. With this format, consumers can see not only what is important in an app’s privacy design but also how it stacks up against competitors. Equally important, the definitions of these terms are broad and meaningful, so items like financial and medical information correspond with consumers’ common sense understandings.

This code is only a beginning. In order to achieve true privacy protections online we must address not just notice but also consent, access, use, and the other baseline privacy principles and we must do so not just through codes of conduct but also through legislation. Negotiating a code that was informative enough to appeal to privacy advocates, usable enough to appeal to consumer groups, and yet manageable enough to appeal to industry was a slow process. In future advances, we cannot spend more than a year discussing every privacy issue. In fact many—including the Obama administration, some companies and the ACLU—agree that the only way to tackle privacy, rein in bad actors, and prevent a race to the bottom is through baseline privacy legislation that sets out rules of the road. After all, we should be able to enjoy cool new technologies without giving up our privacy.

Finally, a word on the National Security Agency spying. Unfortunately we still do not have a clear understanding of the scope of the NSA’s data collection, except that it is enormous and unprecedented and certainly includes many records about what we do online. Nor are many of the companies who are subject to the demands of the NSA free to talk about the scope of those requests. As such this code isn’t able to provide transparency on NSA data collection.

Despite its limitations, we are pleased to support this code. We believe that it advances consumer privacy and demonstrates that industry and consumer organizations can work together to find solutions. The ACLU looks forward to continuing this partnership with the Obama Administration and key industry stakeholders to discuss other important privacy issues with the goal of establishing meaningful baseline privacy legislation.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.