The government wants our data, whether it’s sitting on our iPhones or in transit across the Internet.

Last week, we learned that the FBI is trying to force Apple to break its own security features in order to access data stored on an iPhone that belonged to one of the San Bernardino shooters. Many predict that this would set a dangerous precedent for future cases — and they’re right. But it’s important to keep in mind that the government’s appetite for data isn’t limited to iPhones. In fact, this is only the latest front in the government’s long-running efforts to access our data wherever it can be found.

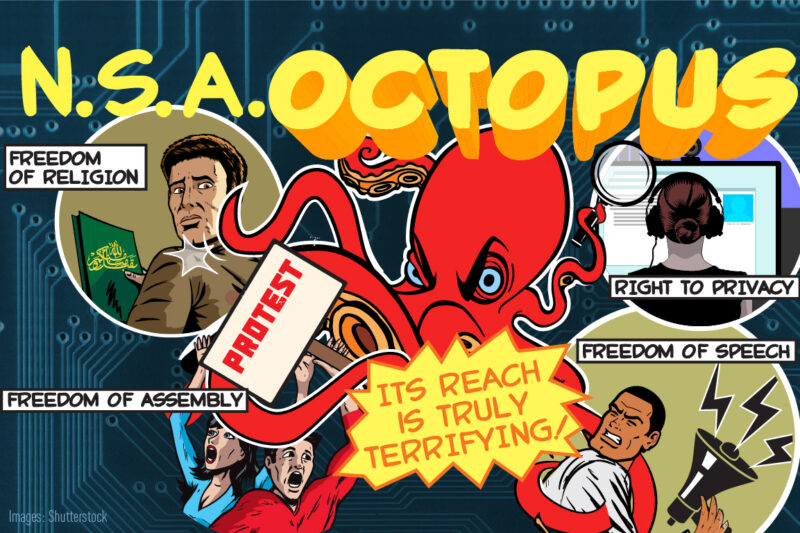

While the country debates what kind of access the FBI should have to the devices we use every day to communicate, the NSA is already intercepting, copying, and searching through vast quantities of our communications as they travel across the Internet backbone from point A to point B. This warrantless spying, known as “Upstream” surveillance, ensnares essentially everyone’s international Internet communications — including emails, chats, text messages, and even web-browsing information. It constitutes a mass intrusion into our privacy online.

With the compelled assistance of the country’s biggest telecommunications providers, such as AT&T and Verizon, the NSA conducts Upstream surveillance by tapping directly into the Internet backbone — the high-capacity cables, switches, and routers that carry Americans’ online communications. The NSA’s surveillance devices are installed at backbone "chokepoints,” major junctions on the Internet through which the vast majority of international communications travel. After copying virtually all of the international text-based traffic, the NSA searches this traffic for key terms, called “selectors,” that are associated with its thousands of targets. Critically, however, the NSA isn’t just plucking out the communications of suspected terrorists or spies. Instead, it’s drinking from a firehose: It’s copying and searching nearly everyone’s international communications, looking for information about its targets. And it does all of this without a warrant.

In other words, it’s as if the NSA dispatched agents to the U.S. Postal Service’s major processing centers and had them open, copy, and read the contents of everyone’s international mail. If a letter contained something of interest — for example, a reference to a phone number believed to be associated with a target — the NSA would add the letter to its files and retain that copy for later use. Of course, the Fourth Amendment protects us from precisely this kind of general, warrantless search. The government can’t simply open all of our letters to look for those that are potentially of interest to it. There’s no question that this would violate the Constitution, and there’s no reason to treat Americans’ private Internet communications differently.

Last year, the ACLU filed a suit challenging Upstream surveillance on behalf of a coalition of educational, legal, media, and advocacy organizations, including the Wikimedia Foundation. All of the plaintiffs engage in sensitive international communications in the course of their work — with journalists, foreign government officials, victims of human rights abuses, clients, witnesses, and the hundreds of millions of people who read and edit Wikipedia. The dragnet surveillance of these communications by the government undermines the privacy and confidentiality on which the plaintiffs’ work depends.

The case, Wikimedia v. NSA, is now on appeal in the Fourth Circuit, after the district court improperly concluded that the plaintiffs did not have standing to sue because they hadn’t plausibly alleged that the NSA was monitoring their communications. The opening brief in the appeal was filed last week, and yesterday, a number of other groups, including technologists, media organizations, and law professors, filed amicus briefs in support of the plaintiffs.

The surveillance state runs deep. But there’s still plenty of room to fight back.

* * *

The amicus briefs submitted yesterday:

Amicus Brief of Civil Procedure and Federal Courts Law Professors

Amici argue that the district court’s dismissal of plaintiffs’ complaint at the motion-to-dismiss stage was based on a fundamental misapplication of federal pleading standards and should be reversed. At the pleading stage, the court must accept the complaint’s factual allegations as true, but the district court improperly refused to accept plaintiffs’ allegations regarding the NSA’s activities.

Amicus Brief of Computer Scientists and Technologists

Amici explain why, as a technological matter, plaintiffs have established to a virtual certainty that the government is copying and reviewing at least some of their communications.

Amicus Brief of Electronic Frontier Foundation

Amicus EFF argues that Clapper v. Amnesty International USA does not compel dismissal of this case, as plaintiffs have plausibly alleged Article III standing. EFF also explains why other avenues for obtaining judicial review of Upstream surveillance have proven insufficient.

Amicus Brief of First Amendment Legal Scholars

Amici explain why First Amendment standing doctrine is uniquely permissive, and they argue that the district court erred in failing to conduct its standing analysis under the First Amendment.

Amicus Brief of Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press et al.

Amici argue that the district court erred in characterizing plaintiffs’ claims as speculative, pointing to the concrete ways in which Upstream surveillance has created well-documented chilling effects on the journalistic profession.

Amicus Brief of U.S. Justice Foundation et al.

Amici argue that official government disclosures make clear that plaintiffs’ communications are subject to Upstream surveillance. This surveillance violates plaintiffs’ rights to privacy and property, and the district court’s failure to reach the merits of the case puts everyone’s liberties at risk.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.