Out of the Darkness

The CIA used the music of an Irish boyband called Westlife to torture Suleiman Abdullah in Afghanistan.

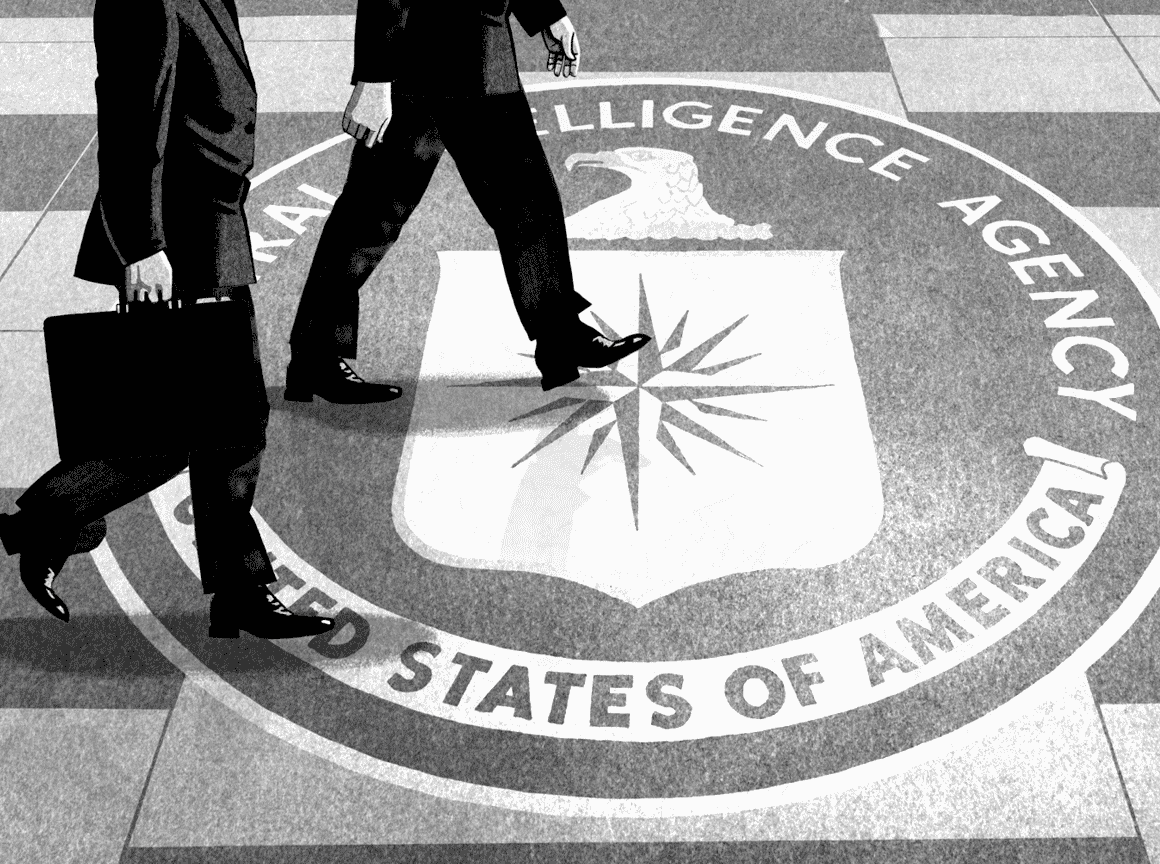

His interrogators would intersperse a syrupy song called "My Love" with heavy metal, played on repeat at ear-splitting volume. They told Suleiman, a newly wed fisherman from Tanzania, that they were playing the love song especially for him. Suleiman had married his wife Magida only two weeks before the CIA and Kenyan agents abducted him in Somalia, where he had settled while fishing and trading around the Swahili Coast. He would never see Magida again.

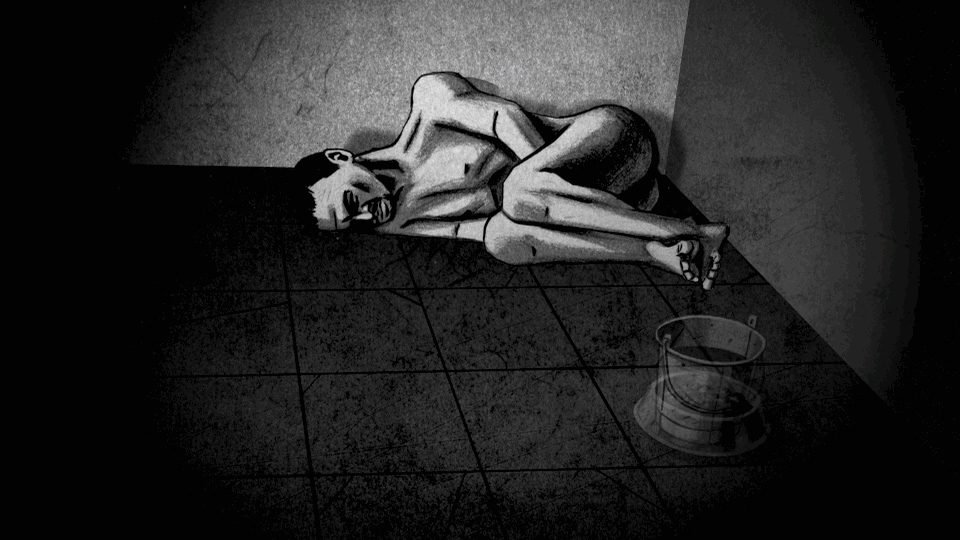

The music pounded constantly as part of a scheme to assault prisoners’ senses. It stopped only when a CD skipped or needed changing. When that happened, prisoners would call to one another in a desperate attempt to find out who was being held alongside them. A putrid smell that reminded Suleiman of rotting seaweed permeated the prison. His cell was pitch black; he couldn’t see a thing. The U.S. government refers to the prison as “COBALT.” Suleiman calls it “The Darkness.”

For more than a month, Suleiman endured an incessant barrage of torture techniques designed to psychologically destroy him. His torturers repeatedly doused him with ice-cold water. They beat him and slammed him into walls. They hung him from a metal rod, his toes barely touching the floor. They chained him in other painful stress positions for days at a time. They starved him, deprived him of sleep, and stuffed him inside small boxes. With the torture came terrifying interrogation sessions in which he was grilled about what he was doing in Somalia and the names of people, all but one of whom he’d never heard of.

After four or five weeks of this relentless pain and suffering, Suleiman’s torturers assessed him as psychologically broken and incapable of resisting them. Suleiman could take no more. He decided to end his life by consuming painkillers he had stockpiled. But as he began to take the pills, guards stormed into his cell to stop him. He was then shackled, hooded, and driven a short distance to another CIA prison close by — a prison Suleiman came to know as the “Salt Pit.” Although Suleiman’s torture would continue for many years more, the very worst of it was over.

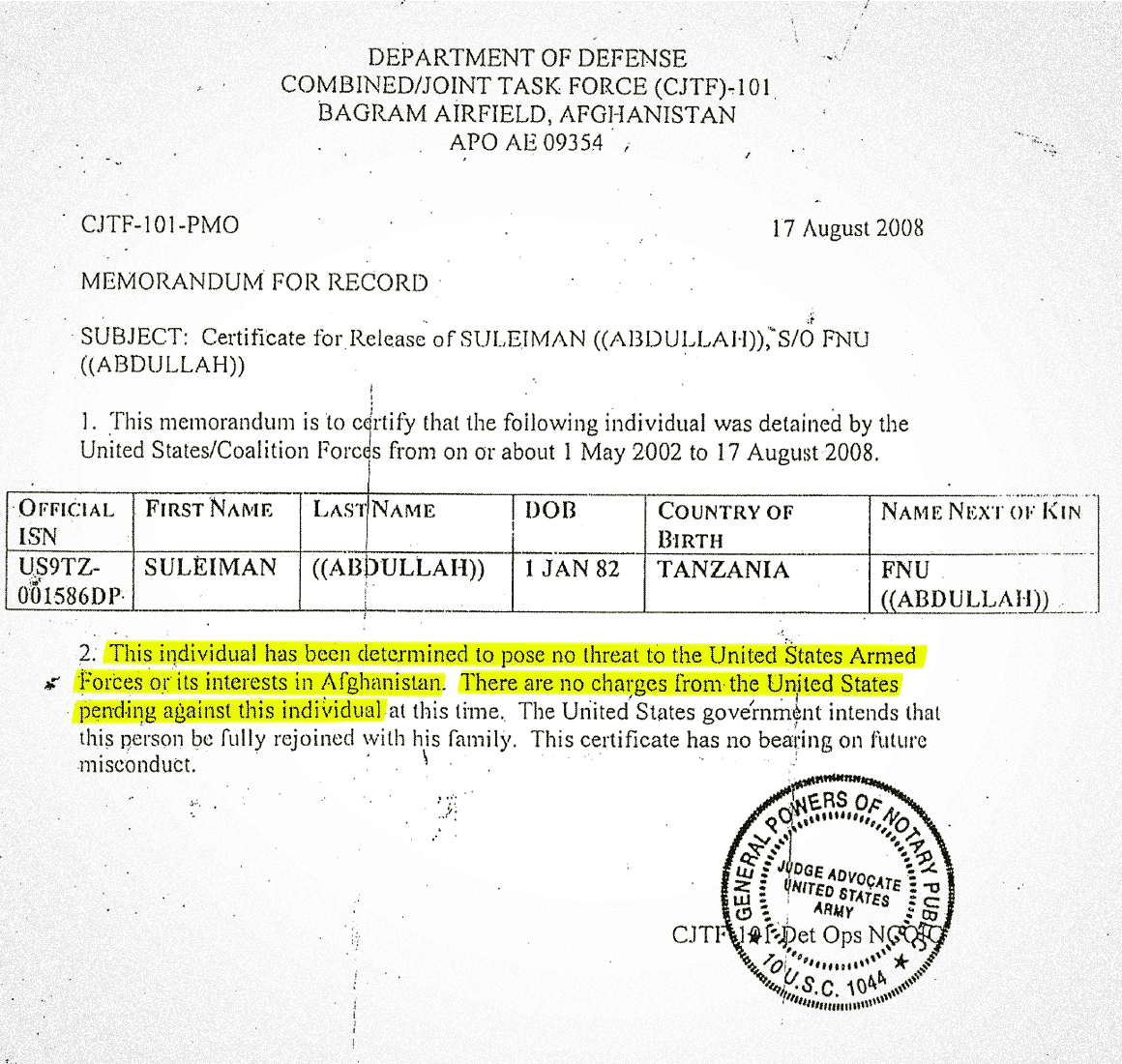

A year and two months later, the CIA handed Suleiman over to the U.S. military, which imprisoned him at Bagram, also in Afghanistan. Finally, in 2008, after more than five years in U.S. custody, with no charges ever leveled against him, he was sent home with a document confirming he posed no threat to the United States. His family had heard nothing of him since his disappearance, and they had presumed him dead.

But even once home in his native Zanzibar, Suleiman felt far from free. Constant flashbacks transported him back to his torture at the hands of his CIA captors. After years of near-starvation he was unable to eat normally. He suffered splitting headaches and pain throughout his body from the torture. Prolonged isolation left him unaccustomed to human interaction. Despite repeated attempts, he couldn’t find Magida. Unable to sleep due to the torment of his memories and the physical pain, he found limited solace playing with his family’s rabbits in the middle of the night.

“I was afraid of so many things,” he says in the halting English he acquired in prison. “Everyone thought I’m crazy.”

Suleiman, a reggae-loving fisherman who had once been known as “Travolta” for his prowess on the dance floor, had become a shell of himself.

Damage by Design

Suleiman’s trauma is not just a consequence of his ordeal in American prisons. It was the CIA’s goal, through a program designed and executed by two psychologists the agency contracted to run its torture operations, to break his mind. Integral to the program was the idea that once a detainee had been psychologically destroyed through torture, he would become compliant and cooperate with interrogators’ demands. The theory behind the goal had never been scientifically tested because such trials would violate human experimentation bans established after Nazi experiments and atrocities during World War II. Yet that theory would drive an experiment in some of the worst systematic brutality ever inflicted on detainees in modern American history. Today, three of the many victims and survivors of that experiment are seeking justice through a lawsuit against the men who designed and implemented that program for the CIA.

James Mitchell, left, and Bruce Jessen, right

VICE News; Wikimedia/Michael Kearns

Mitchell and Jessen were two former U.S. military psychologists contracted by the CIA to design, develop, and run the agency’s detention, rendition, and interrogation operations. As psychologists in the U.S. military’s Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape (SERE) program, the two men had devoted their careers to training U.S. troops to resist abusive treatment in case of capture by governments that violate the Geneva Conventions. SERE teaches resistance by subjecting students to carefully controlled versions of harsh techniques used by China, North Korea, and the former Soviet Union, often to extract false confessions from captives for propaganda purposes. During training, psychologists like Mitchell and Jessen are on hand to monitor trainees’ psychological well-being and to ensure that SERE instructors don’t go too far.

But Mitchell and Jessen intensified and manipulated SERE techniques so they bore little relation to those used on SERE recruits. Whereas SERE training was intended to help strengthen the resolve of American recruits, Mitchell and Jessen’s techniques were designed to achieve the exact opposite result: to break detainees and turn their minds into putty in interrogators’ hands.

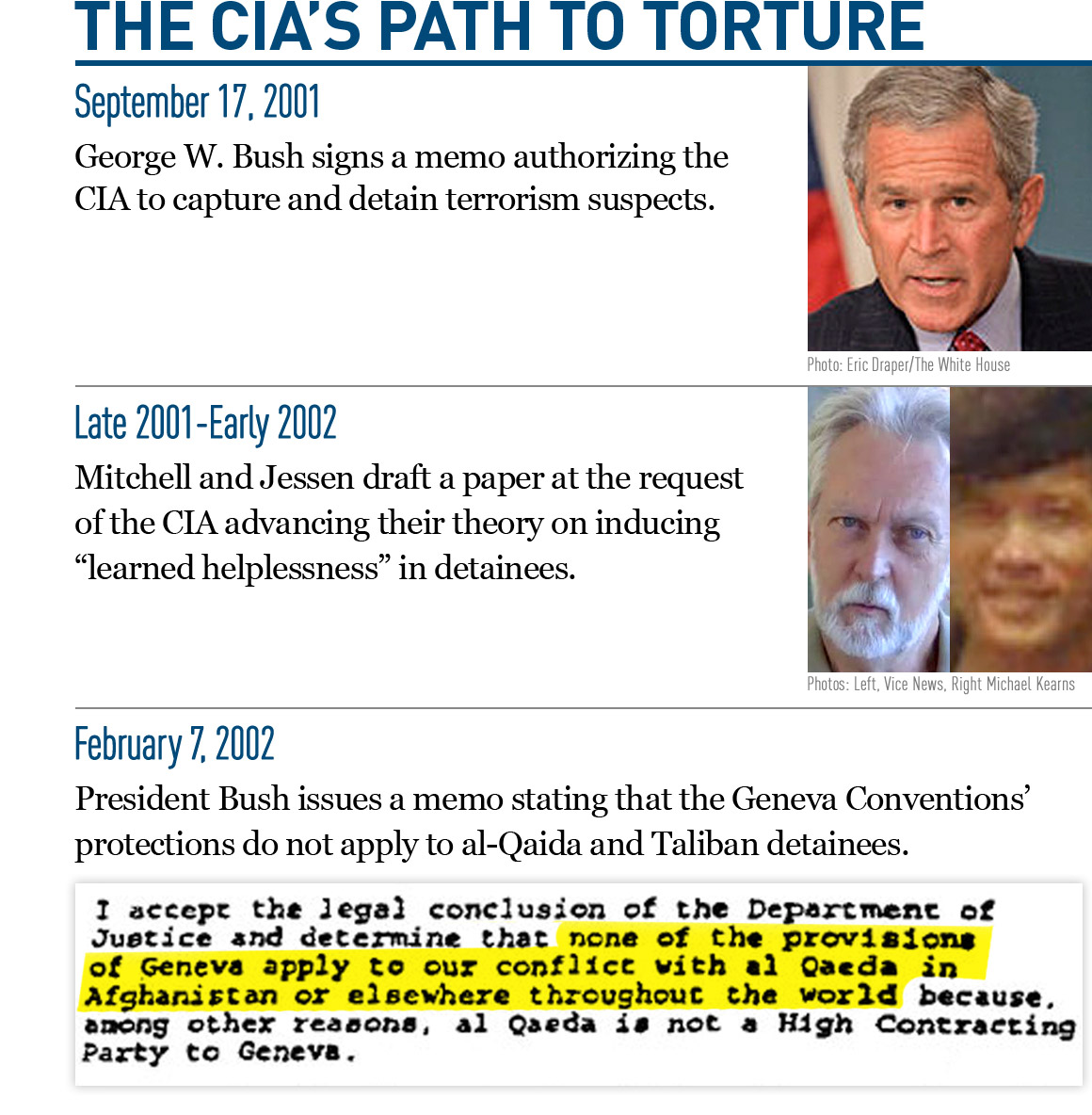

The foundation of Mitchell and Jessen’s experiment in torture began taking shape shortly after the attacks of September 11, 2001. Six days later, President Bush signed an order authorizing the CIA to capture and detain members of al-Qaida. At the time, the agency had little or no recent experience in detention or interrogation – exposure of its participation in torture in the 1960s and 1980s put an official end to those practices. As the agency scrambled to put together the detention component, it also began to explore coercive ways of interrogating detainees, and its prior disavowals of torture began to disintegrate. By November 2001, before it had any detainees in its custody, CIA attorneys had begun drafting opinions on when it would be legally permissible to circumvent the international prohibition on torture.

It was against this backdrop — of an agency with little to no experience in detention and interrogation, presuming the necessity of torture and preemptively seeking cover for illegality — that Mitchell and Jessen entered the scene.

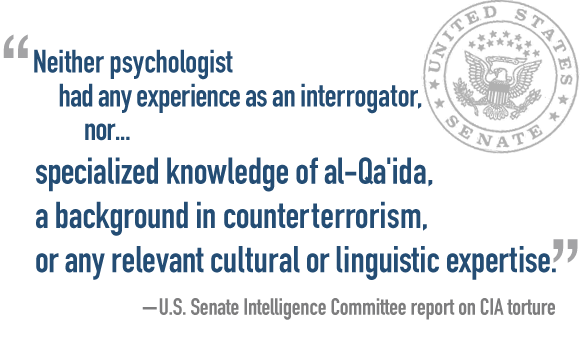

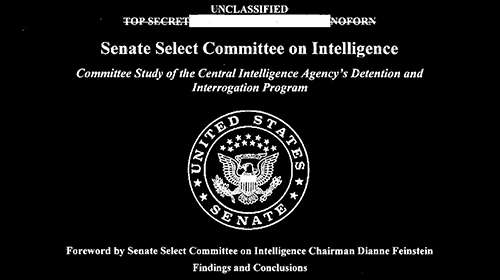

Neither psychologist had ever conducted a real-world interrogation. The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence confirms this in its landmark report on the CIA detention and interrogation program, the executive summary of which was released at the end of last year. “Neither psychologist had experience as an interrogator, nor did either have specialized knowledge of al-Qa'ida, a background in terrorism, or any relevant regional, cultural, or linguistic expertise,” the Senate report notes.

But the CIA was casting around for guidance, and despite this obvious lack in credentials, in December 2001 the agency commissioned Mitchell and Jessen to review the so-called Manchester Manual, a document discovered in Britain that the CIA thought instructed al-Qaida operatives on how to resist interrogation.

Mitchell and Jessen’s review of the Manchester Manual claimed that members of al-Qaida had been trained to resist interrogation and proposed ways to defeat that resistance. Titled “Recognizing and Developing Countermeasures to Al-Qa’ida Resistance to Interrogation Techniques: A Resistance Training Perspective,” the still-classified report laid out the nascent theoretical underpinning for Mitchell and Jessen’s torture program: inducing “learned helplessness” in human beings.

Mitchell and Jessen were interested in applying the psychological concept of “learned helplessness” to interrogation. Psychologist Martin Seligman pioneered studies on the phenomenon in experiments he conducted on dogs in the 1960s. Seligman used the term “learned helplessness” to describe the state of utter passivity prompted by a series of negative events that leads subjects to believe there is nothing they can do to escape their suffering. Seligman conducted his experiments by administering electric shocks to different groups of dogs. When given the chance to avoid their pain, the dogs in his experiment that had been able to escape the shocks did so quickly. Those that couldn’t stop the pain didn’t even try to avoid it, even when given the opportunity. They believed they had no ability to control their fates. They had learned helplessness.

Mitchell and Jessen posited that this theory could be applied to interrogation — that harsh measures could be used to break any resistance of al-Qaida captives by inducing a state of learned helplessness. Torture would “shape compliance” with interrogation, Mitchell and Jessen theorized. Once detainees were abused to the point of learned helplessness, resistance would crumble, and the detainees would divulge information that they might otherwise withhold.

No legitimate science backs up this assumption. Research on inducing a sustained state of learned helplessness in humans through abuse, or on the role of learned helplessness in eliciting truthful information, does not exist for the simple reason that it can’t be legally or ethically conducted. In the words of psychologist Dr. Steven Reisner, an anti-torture advocate and ethics advisor for Physicians for Human Rights:

Inducing a state of learned helplessness in humans, I think without doubt, would constitute torture — cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. Which is the reason why we can't do such experiments, because just envisioning, just actually setting up such an experiment, is a violation of human dignity and a violation of the prohibitions against cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment.

But torture was a key component of Mitchell and Jessen’s plan from the outset. And even under the Bush administration’s skewed reinterpretation of the term, the intentional infliction of physical or psychological pain or suffering severe enough to cause a prolonged mental condition, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, violates the prohibition on torture.

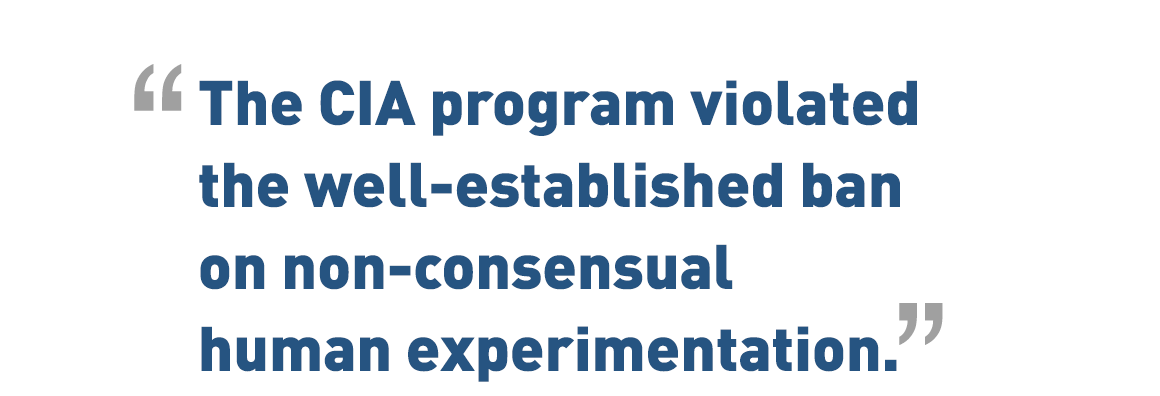

The CIA program violated not only international and U.S. prohibitions on torture — it also violated the well-established ban on non-consensual human experimentation. The Nuremberg Code, in place since 1947, was the basis for the prosecution and convictions of World War II Nazi doctors. It forbids any research on human subjects without their informed consent. Numerous other treaties and ethics codes include similar bans, recognizing that any experimentation, however benign, on human subjects without their consent or on prisoners, is inherently cruel, inhuman, or degrading.

Mitchell and Jessen, however, were undeterred by law, ethics, or the lessons of history. The torture program they designed and implemented at the behest of the CIA by its very design required ongoing experimentation on its human subjects. They did not know how the detainees would react to the torture techniques they devised, or if the detainees would even survive them. They did not know whether and how much torture would be needed to induce learned helplessness in a particular detainee, or whether once a detainee’s mind was broken, he would produce truthful information. They had, after all, adapted the torture techniques from those used by authoritarian regimes to extract false confessions.

The CIA knew it needed legal cover to torture — to “work,” as Dick Cheney characterized it, “the dark side.” By early 2002, the CIA, the Justice Department, and the National Security Council were debating whether the legal and humanitarian protections of the Geneva Conventions would apply to captives suspected to be members of al-Qaida or the Taliban. After weeks of debate, and over objections from the State Department, President George W. Bush ultimately issued the final word on the matter. In a February 2002 memo, he stated that al-Qaida and Taliban detainees were not protected by the Geneva Conventions.

With the decision to set aside one of the most important rights instruments in international law, the U.S. government officially broke ground for the CIA’s torture experiment.

Launching the Experiment

In late March 2002, a joint CIA-Pakistani operation led to the capture of Abu Zubaydah, a Palestinian national born in Saudi Arabia, who, at the time, the CIA thought to be a senior-level al-Qaida operative who possessed detailed knowledge of the organization’s plans. (This assessment "significantly overstated" his role and the information he possessed according to the Senate report.) Mitchell and Jessen now had an opportunity to turn their torture theories into practice. After the CIA rendered Abu Zubaydah to a black site in Thailand, the two psychologists personally conducted and evaluated his interrogation. As the CIA’s first captive, they considered him a guinea pig for their experiment and would come to trumpet his torture as an unmitigated “success” and a "template" for the program’s future implementation.

With Abu Zubaydah’s capture, the debate within the CIA and the Bush administration about the prohibition on torture intensified. Initially, the FBI questioned Abu Zubaydah while he was hospitalized in Pakistan for severe injuries sustained during his capture. As has been extensively reported, the FBI agents used non-coercive, “rapport-building” techniques in their interrogations. Abu Zubaydah cooperated, quickly yielding significant intelligence. The CIA would later misrepresent the source of this intelligence, claiming that it was extracted through torture.

But the CIA had also dispatched an interrogation team, including James Mitchell. In contrast with the FBI’s approach, Mitchell and the CIA recommended that once Abu Zubaydah was released from the hospital that his interrogation begin by keeping him awake, in an all-white and constantly lit room, and for his cell to be bombarded by constant loud noise. What they called the “conditioning” phase, we know from the Senate report, was meant to lay the groundwork for learned helplessness:

[D]eliberate manipulation of the environment is intended to cause psychological disorientation, reduced psychological wherewithal for the interrogation, and the deliberate establishment of psychological dependence upon the interrogator, and an increased sense of learned helplessness.

These and other “conditioning” techniques — including forced nudity, solitary confinement, extreme temperatures, sleep deprivation, and various forms of sensory deprivation — would be formally incorporated into the program. They were designed to instill fear, apprehension, and dread, and to render detainees who were resistant to interrogation more vulnerable to what Mitchell and Jessen considered the harsher techniques to follow.

According to the Senate report and to Ali Soufan, one of the FBI agents who interrogated Abu Zubaydah, Abu Zubaydah quickly shut down when the CIA intervened to introduce its “new interrogation program” on April 13, 2002. A conflict between the two agencies quickly mounted. An anecdote illustrates the agencies’ different approaches: At one point Abu Zubaydah was kept naked by the CIA, and then he was offered a towel to cover himself when questioned by the FBI.

In late April 2002, deeming Abu Zubaydah "uncooperative," CIA headquarters considered three different interrogation strategies for use on him. It selected James Mitchell’s plan, the most coercive of the three, officially choosing an uncharted experiment on human beings as its preferred approach.

The FBI team would soon pull out of the interrogation in protest. “We don’t do that,” Soufan later quoted his boss, then FBI Director Robert Mueller, as saying.

By July, Mitchell and Jessen were lobbying the Department of Justice to approve even more coercive torture methods, which they and the CIA euphemistically called “enhanced interrogation techniques,” for use on Abu Zubaydah. The CIA falsely represented that these techniques were the same as those used in SERE trainings, but the differences rendered the comparison absurd. In addition to the strict safeguards imposed on SERE methods, recruits participated in the program voluntarily and they knew it would end. They were able to use "safe words" to indicate when a mock interrogation had become too stressful. Whereas SERE required that “maximum effort will be made to ensure that students do not develop a sense of ‘learned helplessness’” during training, removing that red line in the torture of detainees was integral to success as Mitchell and Jessen defined it.

To secure Justice Department approval to use the torture methods devised by Mitchell and Jessen, the CIA claimed falsely that Abu Zubaydah was continuing to withhold information about future attacks on the United States. (Interrogators later determined that he did not possess such information.) This indicated, they maintained, that he had not been sufficiently broken psychologically and that harsher techniques were necessary.

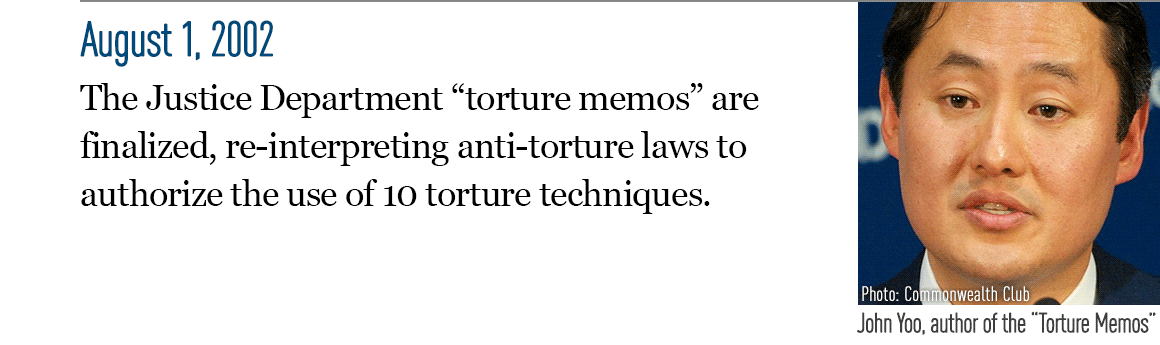

After extensive debate, Deputy Assistant Attorney General John Yoo’s position, that the techniques wouldn’t violate the prohibition on torture, was enshrined in the infamous “torture memos” of August 1, 2002. In one of those memos, signed by then Assistant Attorney General Jay Bybee, Yoo rewrote the legal definition of torture to allow the torture program to proceed. Torture, according to that memo, “must be equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death.” Yoo also advised that for mental pain or suffering to amount to torture, “it must result in significant psychological harm of significant duration, e.g., lasting for months or even years." Another memo released that day approved the use of 10 of Mitchell and Jessen’s techniques, including the waterboard, which the psychologists had insisted was necessary to make Abu Zubaydah compliant. (This despite the fact that, as the Senate report notes, “they had no experience with the waterboard.”)

On August 4, 2002, Mitchell and Jessen, who at this point were paid $1,800 per day by the CIA, began personally administering the torture techniques approved in the memos. Over the course of three weeks, they repeatedly slammed Abu Zubaydah into walls, forced him into coffin-like boxes for hours at a time, beat and waterboarded him, and more. During one session on the waterboard, he “became completely unresponsive, with bubbles rising through his open, full mouth,” according to the Senate report. His wounds, which hadn’t yet healed from his surgery, significantly deteriorated.

In between the sessions, the conditions designed to assault Abu Zubaydah’s senses persisted. He remained in solitary confinement throughout the period, naked, hooded, on a liquid diet, and chained in varying stress positions designed to cause him pain and deprive him of sleep. Loud rock music blared constantly in his blinding white-lit cell.

Within days, personnel at the Thai black site expressed concern that the psychologists were going too far. "Several on the team profoundly affected … some to the point of tears and choking up," one email stated. As early as August 9, CIA personnel told CIA headquarters that they didn’t believe Abu Zubaydah was withholding information from his interrogators. However, they were repeatedly rebuffed and told that enhanced interrogation techniques should continue.

Meanwhile, Mitchell and Jessen were succeeding in breaking Abu Zubaydah. A cable from the prison reported that when an interrogator — most likely Mitchell or Jessen, who were assigned sole responsibility for Abu Zubaydah — would snap his finger twice, “Abu Zubaydah would lie flat on the waterboard.”

While Mitchell and Jessen eventually achieved their goal of psychologically destroying Abu Zubaydah, he did not provide significant intelligence after the enhanced techniques were applied, according to the Senate report.

Still, Mitchell and Jessen would ultimately deem the interrogation a success, telling the CIA that the “aggressive phase… should be used as a template for future interrogation of high value captives.” This wasn’t, however, because Abu Zubaydah had provided information, but because they proved he wasn’t withholding important intelligence:

Our goal was to reach the stage where we have broken any will or ability of subject to resist or deny providing us information (intelligence) to which he had access. We additionally sought to bring subject to the point that we confidently assess that he does not/not possess undisclosed threat information, or intelligence that could prevent a terrorist event.

As Mitchell and Jessen explained in an email to the CIA, sent two days before they stopped his torture, Abu Zubaydah was “ready to talk” the first day after they used their techniques on him: “As for our buddy; he capitulated the first time. We chose to expose him over and over until we had a high degree of confidence he wouldn’t hold back.” According to this twisted logic, torture was both a means and an end. “Success” meant breaking a subject’s mind through torture to ensure the absence of information.

Today, Abu Zubaydah is imprisoned at Guantánamo. He continues to suffer as a result of the torture. He has permanent brain damage. He suffers from searing headaches, sensitivity to noise, and seizures. He can’t recall his father’s name or his own date of birth.

Calibration

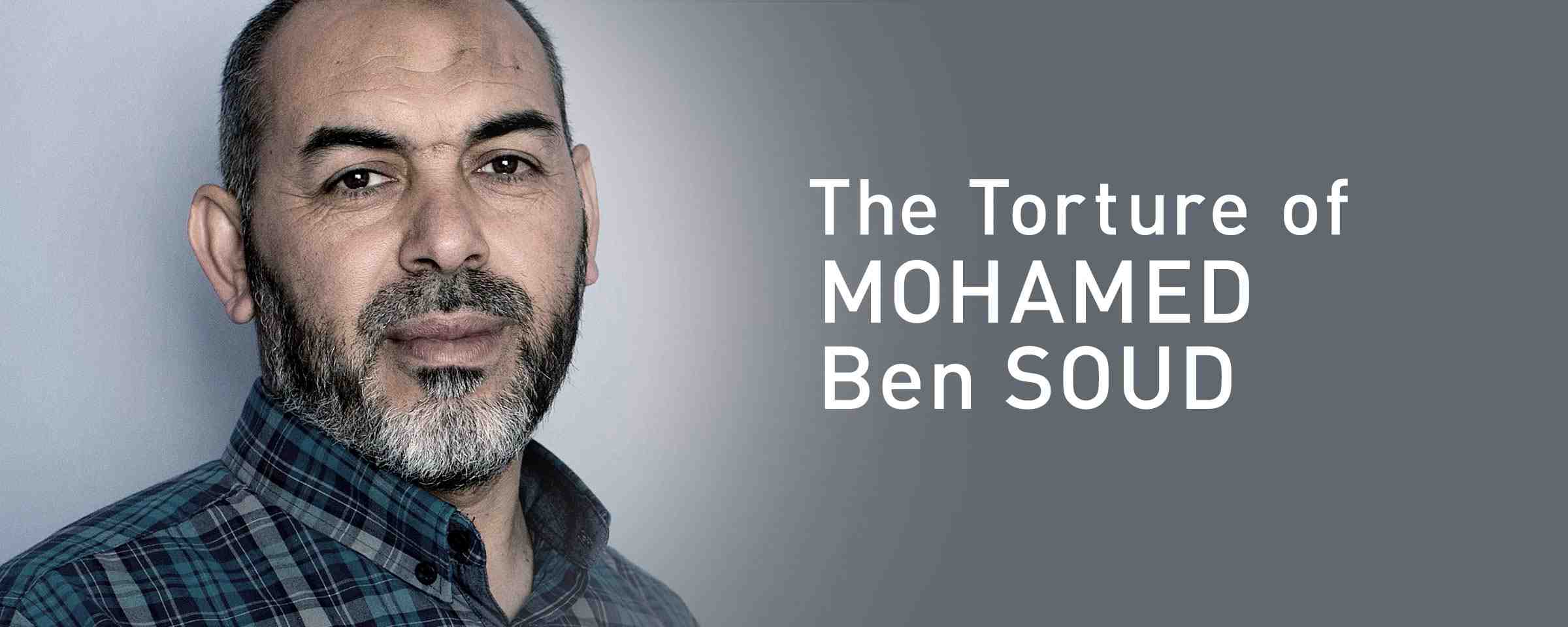

“That’s him,” Mohamed Ben Soud said earlier this year in a meeting with his lawyer, ACLU Staff Attorney Steven Watt, pointing at a photo of James Mitchell. “He was there.”

Mohamed saw James Mitchell several times while he was imprisoned at COBALT, where the CIA held him for a year following his capture in April 2003 during a joint U.S.-Pakistani raid on his home. Mohamed fled his native Libya in 1991, fearing his persecution for his opposition to the Gaddafi regime. He was living in Pakistan with his wife and infant child at the time of his disappearance. As Human Rights Watch has detailed, a rapprochement between Washington and Gaddafi resulted in Libya supplying the United States with the names of citizens it claimed were terrorism suspects.

Mitchell, Mohamed says, made an appearance at his water torture sessions at COBALT, the same CIA prison where the agency had held Suleiman a month earlier. Mitchell seemed to be observing and supervising the proceedings. That description accords with what we know from the Senate report about the many facets of Mitchell and Jessen’s roles. The CIA didn’t just contract the two to devise and administer the torture program. It also had them evaluating their own theory and work. That included monitoring the application of torture techniques and calibrating them in accordance with their ultimate goal of inducing learned helplessness.

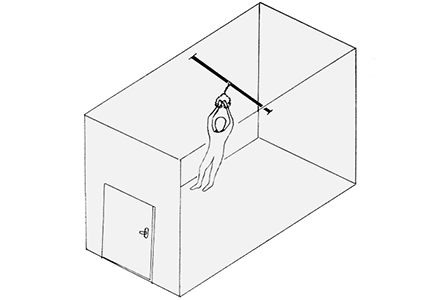

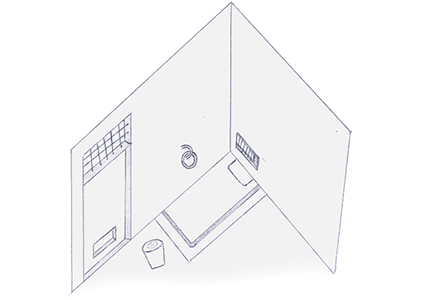

For one-and-a-half days, Mohamed was kept awake in a small pitch-black, noise-filled room, hung by his arms from a metal rod, his feet barely able to touch the floor.

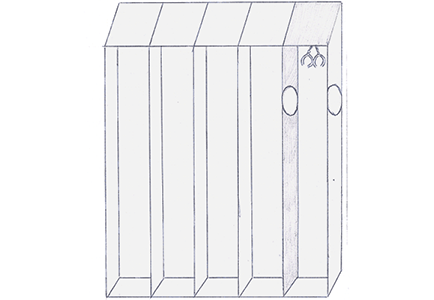

This sketch was provided by Mohamed to the ACLU

CIA personnel would complain about the conflict of interest inherent in the same people evaluating the effectiveness of techniques from which they were reaping enormous profits. The Senate report quotes a CIA Office of Medical Services memorandum reading:

OMS concerns about conflict of interest... were nowhere more graphic than in the setting in which the same individuals applied an EIT which only they were approved to employ, judged both its effectiveness and detainee resilience, and implicitly proposed continued use of the technique - at a daily compensation reported to be $1800/day, or four times that of interrogators who could not use the technique.

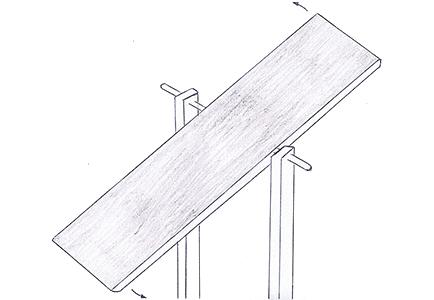

Mohamed was hooded, strapped to a board, and spun around. His interrogators poured buckets of water on his body and threatened to waterboard him.

This sketch by Mohamed was first published in a 2012 Human Rights Watch report, “Delivered Into Enemy Hands."

The course of Mohamed’s torture adhered closely to the “procedures” the CIA laid out in a 2004 memo to the Justice Department. Even before arriving at COBALT, Mohamed was subjected to “conditioning” procedures designed to cause terror and vulnerability. He was rendered to COBALT hooded, handcuffed, and shackled. When he arrived, an American woman told him he was a prisoner of the CIA, that human rights ended on September 11, and that no laws applied in the prison.

Quickly, his torture escalated. For much of the next year, CIA personnel kept Mohamed naked and chained to the wall in one of three painful stress positions designed to keep him awake. He was held in complete isolation in a dungeon-like cell, starved, with no bed, blanket, or light. A bucket served as his toilet. Ear-splitting music pounded constantly. The stench was unbearable. He was kept naked for weeks. He wasn’t permitted to wash for five months.

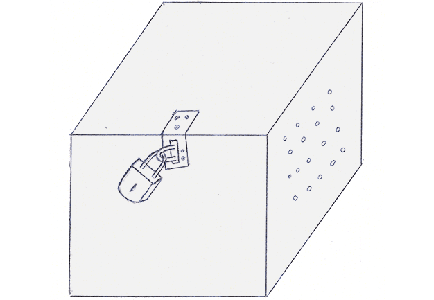

Mohamed was stuffed inside a small wooden box, approximately 3x3 feet, and left alone for 45 minutes.

This sketch by Mohamed was first published in a 2012 Human Rights Watch report, “Delivered Into Enemy Hands.”

For Mohamed, the prolonged sleep deprivation was the most debilitating part of his torture: It drove him close to madness. Mohamed’s torturers kept him awake in many different ways. They chained him in painful stress positions — seated when his broken leg was in a cast, standing once it was removed. Guards banged on his door every hour. Once his broken leg had healed, they added to his torment. Guards would take him from his cell and force him to march around the prison naked for “15 minutes every half-hour through the night and into the morning.” They bombarded him with music. Once, his captors deprived him of sleep for some 36 hours, hanging him naked by his arms from a metal rod where he balanced on the tips of his toes. His legs became engorged with fluid, and he started to hallucinate.

Mohamed was forced into a coffin-like box, about 1.5 feet wide, for 45 minutes. Music was blasted from speakers on the sides of the box.

This sketch by Mohamed was first published in a 2012 Human Rights Watch report, “Delivered Into Enemy Hands.”

Rahman was an Afghan citizen. In 2001, after the U.S.-led invasion of Afghanistan, he fled from the war to Pakistan with his wife and their four daughters. They lived together as refugees in the Shamshatoo refugee camp located on the outskirts of the city of Peshawar. He earned a living selling wood to the other camp refugees. In October 2002, while in Islamabad for a medical checkup, he was abducted in a joint U.S.-Pakistani operation. Shortly after, Gul was rendered to the CIA's COBALT prison in Afghanistan. On November 20, 2002, after being brutally tortured for some two weeks by a team of CIA interrogators that included Bruce Jessen, he was found dead in his cell. An autopsy report and internal CIA review found that Gul likely died from hypothermia caused “in part by being forced to sit on the bare concrete floor without pants,” with the contributing factors of “dehydration, lack of food, and immobility due to ‘short chaining.’” Gul’s family has never been formally notified of his death, nor has his body been returned to them for a dignified burial.

No one has been held accountable for his murder. An unnamed CIA officer who was trained by Jessen and who tortured Rahman up until the day before he was found dead, however, later received a $2,500 bonus for “consistently superior work.”

Mitchell and Jessen made out handsomely too. From 2001 until 2005, as consultants to the CIA, they made $1.5 and $1.1 million, respectively. In 2005, they formed a company, Mitchell, Jessen & Associates, to supply the CIA with more personnel to help implement and expand their program. Until the termination in 2010 of the CIA’s contract with Mitchell, Jessen & Associates, the company received $81 million for its torture services, financed by the American taxpayer.

Mohamed was held in solitary in a small pitch-black cell, 13 feet high and 10 feet long. It was empty apart from a small metal bucket that served as his toilet and a rug to sleep on. He was chained to its wall at all times.

This sketch by Mohamed was first published in a 2012 Human Rights Watch report, “Delivered Into Enemy Hands.”

Rehabilitation

Clara Usiskin, a U.K.-based human rights lawyer, met Suleiman in his native Zanzibar in 2009. He was in terrible shape, struggling with sleeping, eating, and just getting through the day. She helped arrange psychiatric treatment and regular therapy sessions, mostly conducted by phone, and some months later, Suleiman began to get back on his feet.

He has resumed his work as a fisherman, spending as much time as he can at sea to keep his body and mind occupied. After searching to no avail for Magida, he remarried, and he and his second wife have a young daughter. He is still haunted by flashbacks of his time in COBALT, but therapy has helped him to cope with them. With the help of his psychologist, he has worked to turn music back from an instrument of torture to one of comfort and often uses the reggae of Bob Marley or Burning Spear to dispel the terrors that still haunt him.

The document given to Suleiman upon his release from Bagram in Afghanistan in 2008. The date of his initial detention is incorrect.

When Suleiman was held in the Salt Pit, one of his interrogators from COBALT came to see him, bringing with him fruit and nuts. He apologized to Suleiman for torturing him and asked forgiveness. He said he had been forced to do it.

But that’s the extent of the apology anyone associated with the U.S. government has offered Suleiman for his nightmare — his forced disappearance and over five years of arbitrary detention and torture. The U.S. government has given him no formal apology, nor has it aided in his rehabilitation or in that of other CIA detainees, many of whom were quietly sent back to their home countries once the CIA had no further use for them. Suleiman never even received an official explanation, let alone compensation, for his unlawful imprisonment or torture.

The torture program designed and implemented by Mitchell and Jessen ensnared at least 119 men, and killed at least one — a man named Gul Rahman who died in November 2002 of hypothermia after being tortured and left half naked, chained to the wall of a freezing-cold cell.

Gul Rahman

His torturers introduced water torture into their regimen some two weeks after Mohamed arrived in COBALT. They would submerge him naked in ice water, his cuffed hands forced over his head, until a doctor deemed his temperature dangerously low and warm water would be thrown on him. When his cast began to disintegrate from the water, a doctor first covered it in plastic, and when that didn’t work, designed a cast that could be easily removed during the sessions. During later sessions, Mohamed’s torturers placed a hood over his head before he was doused to make him feel like he was drowning.

After some two months of torture in COBALT, Mohamed’s captors stopped the most aggressive phase of his torture, deeming him sufficiently “broken” and “cooperative.” Eight months later, April 2004, Mohamed was transferred to a second CIA-run prison, codenamed ORANGE in the Senate report. He spent the next several months in solitary confinement, chained to the wall when he wasn’t being interrogated. In August 2004, the United States rendered him into the hands of the same Gadaffi government he had fled fearing persecution more than a decade previously. Sentenced to life in prison following an unfair trial, Mohamed eventually won his freedom in February 2011, a day after the start of the revolution that led to Gadaffi’s overthrow. Today, he lives in Misrata, Libya, together with his wife and three young children. Mohamed continues to suffer the effects of his torture at COBALT. He suffers from hearing loss, a damaged sense of taste and smell, and regular pains in his leg, which he can’t walk on for a significant length of time.

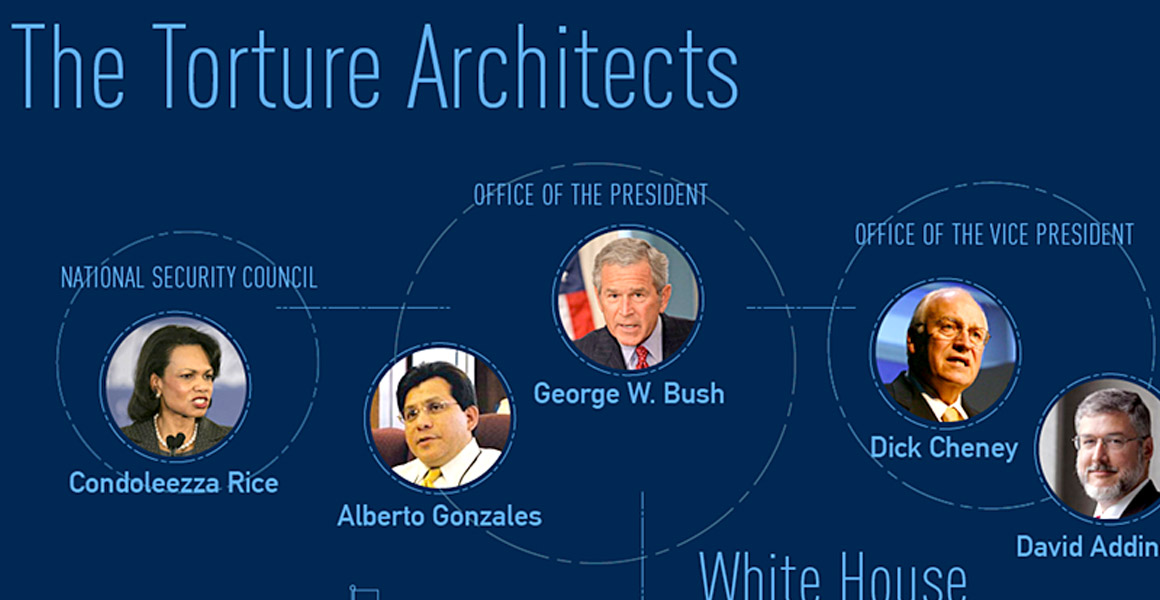

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE TORTURE ARCHITECTs (interactive)

For Suleiman, the release of the Senate torture report last year was a major milestone. He describes the experience of seeing his name in black and white as deeply moving. It was the closest the U.S. government had come to taking responsibility for what it did to him, and it also confirmed his story to those who had doubted his account.

“Many don't believe that Americans do that,” he says. The truth coming out, he adds, “is very good for me, very good for me.”

The Senate report fills in many holes in the public record resulting from years of excessive secrecy. But it is not accountability. The government has prosecuted only a handful of very low-level soldiers and one CIA contractor for prisoner abuse. The architects of the CIA’s torture program, Mitchell and Jessen among them, have so far escaped any form of accountability. In fact, many have gone on to lucrative careers or comfortable retirements.

“We tortured some folks,” President Obama famously said a few months before the release of the Senate torture report summary. “I understand why it happened. It’s important when we look back to recall how afraid people were. People did not know whether more attacks were imminent. And there was enormous pressure on our law enforcement and our national security teams to try to deal with this.”

This analysis is misguided. To be sure, we lived in a time of fear. But the ban against torture is universal and fundamental, applying in times of fear and courage, insecurity and security. And the decision to torture was made deliberately, in a program characterized by human experimentation, intentional brutality, and the painstaking manipulation of the law. It was as clinical as it was cruel. It resulted in the perpetration of terrible crimes completely at odds with U.S. law, international law, and basic humanity.

Accountability is critical for the victims and survivors whose lives were undone, and for all of us who value being part of a nation of laws, one strong enough to acknowledge wrongdoing and make amends.

If this country’s recent experiment in torture continues to be marked by impunity, we risk going down that path again.

No Human Rights on the High Seas | American Civil Liberties Union

Salim v. Mitchell – Lawsuit Against Psychologists Behind CIA Torture Program | American Civil Liberties Union

Senate Torture Report - FOIA | American Civil Liberties Union

Here the Rain Never Finishes | American Civil Liberties Union

How Two CIA-Contracted Psychologists Came to Torture | American Civil Liberties Union