This was originally published by Time.

Eric Garner’s choking death at the hands of New York City police officers might have gone largely unnoticed. His final pleas for air—“I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe.”—might never have served as a rallying cry for racial equality. In most circumstances, his would have been just another death in the troubling statistics of racial disparity.

All this, but for one simple fact: His killing was videotaped. There was incontrovertible and appalling proof of the tragic cause of his death.

This is the power of imagery. It often captures what words can’t. It angers, it frustrates, it provokes. And it is the reason that the American Civil Liberties Union has been fighting in court for more than 10 years for the release of photographs documenting the maltreatment of prisoners in U.S. military custody in the so-called “war on terror.”

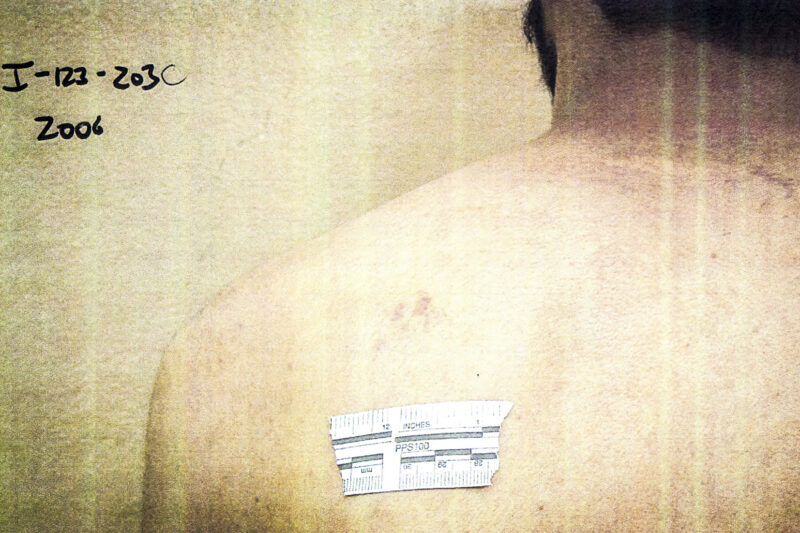

On Friday, the government released 198 of these photographs in our decade-long Freedom of Information Act lawsuit. The photos show mainly close-up photos of bruises and abrasions on prisoners who alleged detainee abuse. The government has described these 198 photos as “benign,” but the truth is that they are disturbing and hint at the brutality of what the government is still keeping secret.

The government’s disclosure is welcome news, but it is far from enough. The photos that the government released are almost certainly the most innocuous from a set of more than 2,000 photos showing the severity of mistreatment of detainees.

The other 1,800 photos—which the government does not want the public to see—are likely similar to the Abu Ghraib photos that shocked the nation when they were leaked in 2004. But this batch is different in a critical respect: Unlike the Abu Ghraib photos, these are from more than two dozen different detention facilities in Afghanistan and Iraq, and so they show the true scope of detainee abuse.

Like the video of Eric Garner’s killing, the photos of U.S. abuse of detainees should be released so that Americans know what was done in their names. They should be released to finally put to bed the false narrative—first perpetuated by the George W. Bush administration, but later adopted by President Barack Obama himself—that prisoner abuse was an aberration, rather than the result of policy or a climate calculated to foster abuse. And they should be released because democracies confront their misdeeds, not conceal them.

Our government has argued that images showing the abuse of prisoners must be suppressed because of the potential for violent backlash. Of course, nobody wants to see anyone get hurt as a result of the release of this, or any other, information. But the reality is that the government’s argument is just a pretext.

When it suits them, politicians have condemned the idea that terrorists should be given a veto over what information is released in our country. This is, in fact, a deeply American principle: The Supreme Court has repeatedly warned against the danger to free expression of a so-called “heckler’s veto.” Our leaders embraced that principle after the heartbreaking attack on Charlie Hebdo in 2015, seemingly unanimous in their rejection of self-censorship as a response to the terrorist attacks.

When the cause is accountability for U.S. government misconduct, however, our leaders have often taken a different tack. They have proposed denying the public powerful evidence of widespread illegality—not to avert a specific and credible threat of harm, but based on the generalized fear that exposing our wrongs will aid the enemy.

This impulse has no place in a democracy. We will always have mistakes to account for, and we will often have enemies poised to violently exploit them. If that combination were enough to defeat the transparency necessary for meaningful accountability, though, our system of checks and balances would fail. There is already a widely shared sentiment that politicians are above the law. Nothing could cement that sense better than to hand them the power to decide which evidence of their misconduct the public is allowed to see.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.