This week I am in Guantánamo Bay observing a hearing in the case of Abd al-Rahim Hussayn Muhammad al-Nashiri (pronounced al-NAH-shiri), the first death penalty case to be tried by military commission. Mr. al-Nashiri faces charges for his alleged participation in the attack on the destroyer USS Cole over 11 years ago. Apprehended in 2002, he was held by the CIA for four years in secret before his transfer to military custody. U.S. officials brutally tortured Mr. al-Nashiri: he was waterboarded, and threatened with a power drill and handgun next to his head. Sadly, this week's pretrial hearing in his case continues to erode the commission's purported commitment to fairness, transparency, and justice and instead affirms a commitment to Guantánamo's shameful legacy of injustice.

Yesterday, Mr. al-Nashiri's defense team argued motions challenging the jurisdiction of the military commissions and the constitutionality of the Military Commissions Act of 2009 that created this iteration of them. Among the challenges: the act singles out noncitizens for prosecution, which is a violation of the Equal Protection Clause. An American citizen who committed the very same or even worse crimes violating the law of war or threatening national security would be tried in federal court. Chief Prosecutor for the military commissions Brig. Gen. Mark Martins circularly maintained that trial in a military commission was appropriate despite this inequality because of the acts al-Nashiri has committed. Nevermind the presumption of innocence.

Judge James Pohl asked the government whether constitutional rights even applied to Mr. Al-Nashiri and other Guantánamo detainees. Gen. Martins said, unequivocally, "no." His answer, reiterated several times, that Mr. al-Nashiri was not entitled to constitutional protections seemed to confirm that the commissions are set up not for fairness but to guarantee convictions through looser substantive and procedural rules than the Constitution requires.

Mr. al-Nashiri is not the first to be tried in this latest iteration of military commissions, but he is the first defendant in this new version of commissions against whom the government is seeking the death penalty. (There were six capital trials pending in 2008 when President Obama was elected: Mr. Al-Nahshiri and the five 9/11 defendants. Those cases were put on hold and ultimately dismissed after his inauguration, but like Mr. al-Nashiri, the 9/11 defendants have now been charged once more. They will be arraigned on May 5.)

Federal constitutional law has long recognized that death penalty cases are different. When the government seeks the ultimate punishment against a criminal defendant, a court must take extraordinary protections to guard against error. As a staff attorney with the ACLU's Capital Punishment Project, I represent defendants charged with serious, tragic crimes and facing the death penalty in courts across the country. I am no stranger to challenging courtroom environments and public hostility towards my clients. But when I walk into a courtroom, I know that if nothing else, I am armed with the Constitution. The Constitution guarantees that my clients have the right to due process, to be tried by an impartial jury, to confront the witnesses against them, to a speedy trial, and to a reliable capital sentencing proceeding. Most importantly in the case of indigent clients – the only ones the ACLU's CPP represents – defendants are entitled to be equipped with the resources necessary to defend against a death sentence, and to ask for those resources in an ex parte proceeding (in other words, without the prosecution present), so as not to tip off the prosecution about defense strategy. If these rights are not honored at the trial court, I know that my client will be able to challenge constitutional errors on appeal. At the military commission, we seem to have left the Constitution on the mainland.

This week's hearing was also expected to test the circumstances under which military commissions will be held in closed session. Of course, already the sessions are far from open. The few observers granted permission by the government to attend the proceedings in Guantánamo view the courtroom from an adjacent room through soundproof glass. We hear the proceedings via an audio feed with a 40-second delay. The government has deemed any utterance from a defendant presumptively classified, in order to censor damning evidence of torture and brutal interrogation methods. In fact, "classified" has been specifically defined to include any words about past torture or present conditions of confinement at Guantánamo. So, if evidence the government wants to keep from the public comes up, a red light goes off and suspends the audio feed for the observers. This is despite the fact that information about torture in CIA custody is already public, and techniques like waterboarding have been admitted by the government.

Mr. al-Nashiri was set to testify yesterday in support of a defense motion challenging his shackling during legal visits. The motion argued that shackling Mr. al-Nashiri during these meetings retraumatizes him, reminding him of the torture he endured at the hands of the CIA. Retraumatization prevents effective attorney-client communication – a critical factor in any case, but even more so in when someone is facing the death penalty, where defense lawyers must ask about sensitive and highly personal evidence that is essential to their representation of a client and may save the client's life.

In anticipation of Mr. al-Nashiri's testimony, the judge heard arguments from counsel about the procedure for closing the courtroom, and in a first for a military commission, the judge allowed a lawyer present on behalf of 10 media companies to argue for openness in the proceedings. Ultimately, the judge dodged the issue by ruling that Mr. al-Nashiri should not be shackled when he meets with his legal team. But the issue of open hearings regarding torture and abuse will undoubtedly surface again soon, in Mr. al-Nashiri's case or in the upcoming military commission proceedings against the five alleged 9/11 perpetrators, over which Judge Pohl will also preside. Torture and abuse should not be covered up, and an important test of these commissions' transparency and fairness will be whether the government is able to censor and keep from the public the torture to which the 9/11 defendants were subjected.

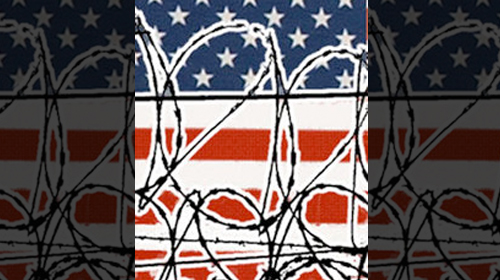

The government is risking the integrity of the possible convictions and death sentences against Mr. al-Nashiri and the five men accused of participating in the 9/11 attacks with this untested and unfair system of justice, where the Constitution may not apply and where the proceedings may be conducted in secret. Our federal courts are well-equipped to handle these cases: the federal government has successfully prosecuted hundreds of terrorism cases in federal court since 9/11, without having to decide novel legal issues at every step and without abandoning the Constitution. In Guantánamo, we are using a second-class system of justice for the most important capital trials in our country's history. Already we are alone among Western nations in our heavy use of capital punishment. Must we also leave our Constitution behind?

Learn more about indefinite detention: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.