This Secret Domestic Surveillance Program Is About to Get Pulled Out of the Shadows

The federal government will have to produce information on a vast and secret domestic surveillance program and defend the program's legality in open court. That's the result of a decision issued Friday by the federal judge presiding over our lawsuit challenging the Suspicious Activity Reporting program, part of an ever-expanding domestic surveillance network established after 9/11.

The program calls on local police, security guards, and the public — our neighbors — to report activity they deem suspicious or potentially related to terrorism. These suspicious activity reports ("SARs" for short) are funneled to regional fusion centers and on to the FBI, which conducts follow-up investigations and stockpiles the reports in a giant database that it shares with law enforcement agencies across the country.

The decision is significant.

Surveillance programs have largely been shielded from judicial review, as many courts have accepted the government's position that people cannot prove they have been under surveillance, and thus lack standing to sue. In this case, we represent clients who were confronted by law enforcement or know that SARs were uploaded to a counterterrorism database based on their entirely lawful activity. The government will now have to turn over information about a program that has never been subject to public scrutiny.

The problems with the Suspicious Activity Reporting program are manifold, beginning with the fact that government doesn't require reasonable suspicion of criminal activity — an already low threshold — for a SAR to be maintained and shared. That violates a binding federal regulation, which is part of the basis for the lawsuit.

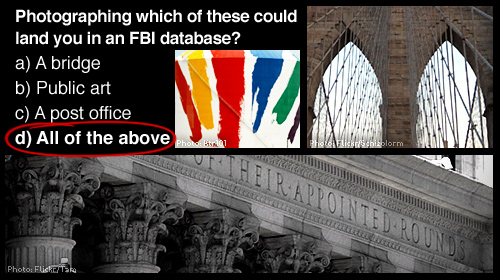

Because the government's loose standards define practically anything as suspicious, SARs end up targeting innocent, First Amendment-protected conduct and inviting racial and religious profiling. Some of our clients, who you can read about here, have been reported for taking photographs. We believe that others were targeted because of racial or religious bias.

The SARs program calls to mind another initiative that is currently all the rage within the government: countering violent extremism, or "CVE." A key part of the CVE initiative would encourage teachers, religious leaders, and even parents to monitor and report to law enforcement individuals at potential risk of drifting toward violent extremism. Like the SAR program, the CVE initiative uses vague, expansive guidelines to decide what should be monitored — factors that can include expressing political or religious beliefs. Under CVE, normal teenage behavior could be an indicator of the potential to engage in terrorism.

The National Counterterrorism Center has even proposed a system for rating individuals on things like "connection to a group identity," families on "parent-child bonding," and communities on access to health care and social services, in order to produce a numerical score reflecting the risk of "susceptibility to engage in violent extremism."

Reducing individuals, families, and communities to a risk score based on subjective assessments of their health and well-being – or perfectly innocuous activity – is both repugnant and unsupportable. Like many of our nation's post-9/11 national security programs, and despite assurances to the contrary, the focus of the CVE initiative has clearly been on American Muslim communities, increasing the stigma to which they have been subjected and their distrust of law enforcement.

Friday's ruling in our SARs challenge is a step toward transparency and accountability. We'll now have the opportunity to seek information from the government on the scope and effects of the SARs program — an opportunity the public should have had before the program was implemented. All indications are that the CVE initiative requires the same public scrutiny too.

Learn more about government surveillance and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.