Arizona Officials Say It’s Unsafe for Prisoners to Read About Race and Criminal Justice. They're Wrong.

UPDATE: On June 18, 2019, the Arizona Department of Corrections responded to the ACLU’s letter and confirmed that Chokehold: Policing Black Men will now be allowed into its facilities.

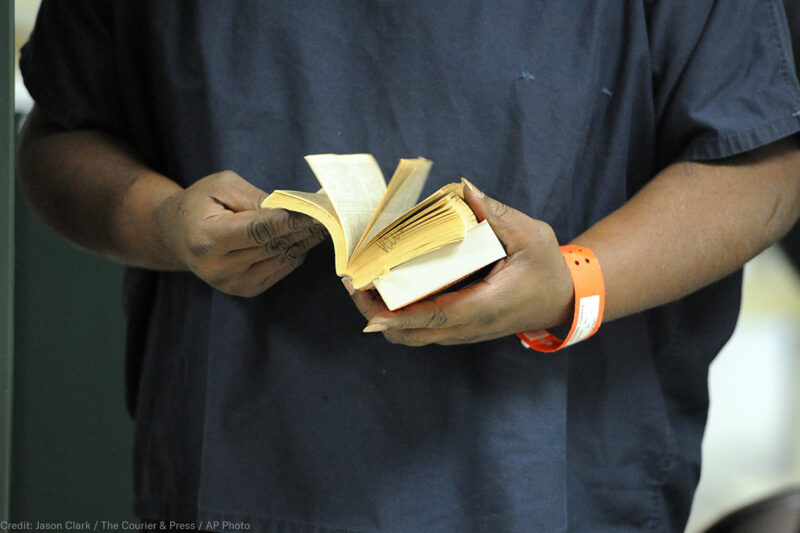

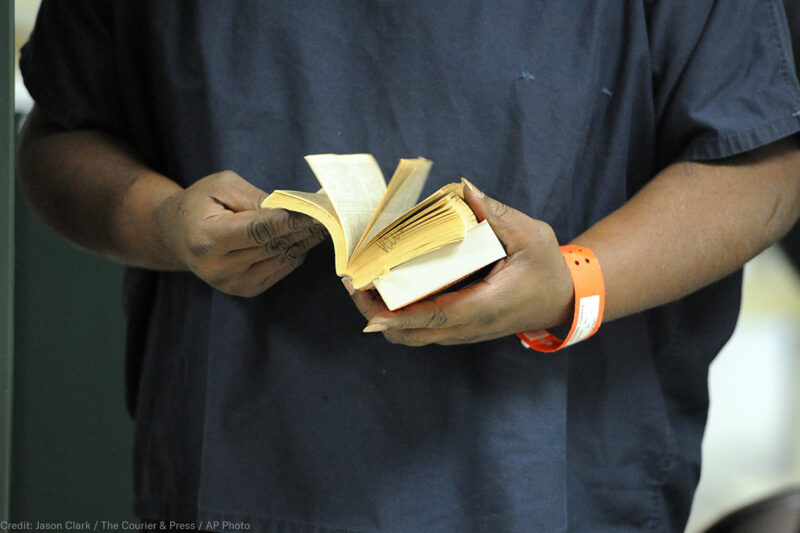

For many people behind bars, books can be a lifeline to the outside world. In the words of poet, attorney, and former prisoner Reginald Dwayne Betts, “Books weren't really magic when I was a child, they were just something that I [enjoyed] reading. I thought it was important, but when I got locked up it became magic, it became a means to an end.”

Prisons are not, and should not be, just punitive institutions. They should also be rehabilitative, which becomes especially clear when you consider that 95 percent of incarcerated people will return to their communities. If prisons and jails take rehabilitation seriously—and people behind bars are to have genuine opportunities to build a foundation for when they leave—access to educational material is critical. Books provide one of the few opportunities for self-directed education, entertainment, and self-improvement at virtually no expense to the government.

That’s why the Arizona Department of Corrections’ (ADC) recent ban on Paul Butler’s book, “Chokehold: Policing Black Men,” is so misguided. The ADC claims that allowing prisoners to read the book would be “detrimental to the safe, secure, and orderly operation” of its prisons, but that is absurd.

Butler, a former federal prosecutor, uses the chokehold — a deadly tactic used by police officers to force people into submission — as a metaphor to explore the history and practical implications of racial oppression within the U.S. criminal justice system. “Chokehold” provides a guide for Black men who may encounter the criminal justice system, evaluates tactics used in social movements to promote reform, and charts a path for a safer and more just society. Prison, Butler argues, is not the answer.

And yet, nothing in the book is even remotely dangerous. In fact, Butler describes “violence against police officers, or any other persons” as “unjustified, on moral grounds and because it would hurt the movement.”

As we explain in our demand letter to the ADC, this ban is not only unnecessary and inhumane —it’s also unconstitutional. ADC officials cannot deny prisoners access to a book simply because it is critical of prisons.

The First Amendment protects both the rights of prisoners to access information and the rights of people in the outside world to communicate with people who are incarcerated. Any attempt to restrict these rights must be reasonably related to achieving the prison’s legitimate goals, and the Supreme Court has prohibited restrictions that represent an “exaggerated response” by prison officials. Banning a book about the social and institutional forces that shape prisoners’ own lives is exactly the kind of “exaggerated response” the Supreme Court was worried about.

Indeed, this is not the first time ADC has unconstitutionally prevented Arizona prisoners from accessing educational material. In March of this year, a federal court found that ADC’s ban on written and visual depictions of sex violated the First Amendment because it was “not rationally related to its stated goals of rehabilitation, reduction of sexual harassment, and prison security.” The court highlighted the fact that the censored material addressed allegations of sexual harassment and assault which occurred in prison. In the same way, “Chokehold” speaks to prisoners’ very situation of incarceration.

ADC’s rationale implies that well-informed prisoners are inherently dangerous. The irony is that ADC’s overreaction is evidence of “Chokehold’s” hypothesis — that the criminal justice system is designed to punish Black men.

Censoring books isn’t just a problem in Arizona. A Georgia jail system just implemented one of the strictest bans we’ve seen, preventing prisoners from possessing any books other than a bible. Michelle Alexander’s “The New Jim Crow” has been banned in prisons in North Carolina and Florida (though North Carolina lifted the ban a few days after the New York Times story published).

Still, the data show that prison reform is as needed in Arizona as anywhere else. As of 2016, Arizona had the fourth highest imprisonment rate in the United States. And Arizona’s criminal legal system has the highest rate of imprisoned Latinos and the sixth highest rate of imprisoned Black people.

Restricting access to information about the social and institutional forces that shape prisoners’ own lives—instead of providing prisons that meet standards of decency and dignity—dehumanizes prisoners and is a disservice our democracy and society.

So what can be done?

Well, if a prisoner or publisher wants to contest a book ban, they should be sure to read the small print. ADC policy says that if you appeal, you agree to unlimited redactions of the material in question. This procedure leaves people with no meaningful recourse once a book has been banned. Public outcry — or a suit in federal court — may be the only way to compel ADC to reverse its decision.

Since the appeal process is entirely unhelpful, we decided to send ADC a letter and give it a chance to correct its serious misstep. Given the well-established Constitutional protections for access to literature in prison and the relevance of Butler’s book to those currently incarcerated, the ADC must lift the ban and loosen its own psychological chokehold on prisoners.