This piece originally appeared at Solitary Watch.

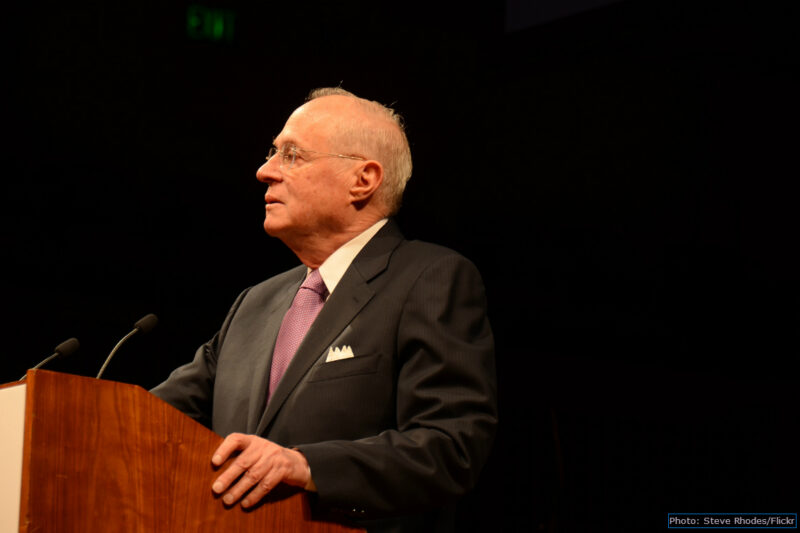

In March, Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy was testifying before the House Appropriations Subcommittee when he received a question on prison overcrowding. He responded with a sweeping condemnation of the American prison system. “Total incarceration,” he stated, “just isn’t working.” He reserved his harshest words for the practice of solitary confinement: “Solitary confinement literally drives men mad.”

Justice Kennedy’s words were powerful but also left an open question. He called the prison system “overlooked” and “misunderstood,” lamenting that, “We have no interest in corrections.” But he is no outside academic, critiquing the inattentiveness of others. He is a member of a court both able and required to ensure that conditions inside prisons comport with the Constitution. Indeed, he is often the court’s swing justice, casting the deciding vote on what the Constitution requires. His influence in determining constitutional questions has led law professor Noah Feldman to write, “It’s Justice Anthony Kennedy’s country — the rest of us just live in it.” If solitary confinement were indeed a primary concern for the justice, when would it make its way to the pages of the Supreme Court’s opinions?

Last Thursday, it arrived. In Davis v. Ayala, the United States Supreme Court decided an unrelated question on the exclusion of a defense attorney from part of a hearing on jury selection. The defendant, however, had spent much of the past 20 years in solitary confinement, and Justice Kennedy wrote a separate concurrence to address the practice.

Justice Kennedy opened with the long cultural history of the horrors of solitary confinement, citing an 18th century report on prison conditions and a 19th century novel that detail the damage solitary confinement has wrought. He continued to 1890, when a United States Supreme Court case described how even short stints in solitary left people “violently insane.” He connected these trends to the present, citing to the story of Kalief Browder, a child who spent years in solitary confinement while being held, though never tried, for allegedly stealing a backpack. Earlier this month, Browder took his own life.

While this long-standing knowledge of the dangerousness of solitary confinement was “[t]oo often” and “[t]oo easily ignored,” Kennedy wrote, a “new and growing awareness” on solitary confinement is emerging. Most significantly, he closed by appearing to invite a case to address these concerns directly: “In a case that presented the issue, the judiciary may be required, within its proper jurisdiction and authority, to determine whether workable alternative systems for long-term confinement exist, and, if so, whether a correctional system should be required to adopt them.”

When a Supreme Court justice talks, the world listens. The New York Times dedicated an editorial to the concurrence, writing that Justice Kennedy “raises a constitutional question even if some of his colleagues would rather avoid it.” The Los Angeles Times wrote of the “rare instance of a Supreme Court justice virtually inviting a constitutional challenge to a prison policy.”

Slate chided Justice Kennedy for his lack of self-awareness in accusing others of apathy: “Kennedy may have only just discovered the cruelty of solitary confinement, but civil-liberties-minded individuals and advocacy groups have fought against the practice for decades.” As civil rights lawyers leading the ACLU’s Stop Solitary campaign, we know well that advocates have worked for years to confront the practice, but there is also no question that the justice’s concern reflects a new and growing national movement to end solitary confinement. That movement now has one of the nation’s leading moral and legal voices as its center.

From both a legal and cultural perspective, however, what may be most significant is not Justice Kennedy criticizing the practice or calling for a case on solitary confinement, but the kind of case that he may be seeking. The extant law on the issue often focuses on keeping vulnerable populations out of solitary. For example, courts have ruled that the 8th Amendment limits the placement of people with serious mental illness in solitary. Courts have similarly found that putting people with physical disabilities in solitary can violate federal law. The New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision settled a lawsuit in 2014, agreeing to keep pregnant women out of extreme isolation. Legislative and executive solitary confinement reform often follows the same pattern, restricting the use of solitary confinement for a particularly vulnerable population, such as children.

While these reforms have been critically important, there is legal precedent to think about the question differently. In 2002, the Supreme Court in Hope v. Pelzer found an Alabama prison’s practice of handcuffing prisoners to a hitching post for violating prison rules to be unconstitutional. Instead of examining the punishment as just another condition of confinement, the court found the punishment to be “antithetical to human dignity” and therefore a violation of the 8th Amendment.

This is the legacy Justice Kennedy appears to invoke in his concurrence, of solitary confinement as not just another potentially harmful prison practice but as a violation of human dignity. The concurrence begins not with the latest social science but instead by describing the centuries long cultural understanding and criticism of solitary confinement. Most significantly, the concurrence does not once single out a vulnerable or sympathetic subset of people held in solitary confinement. Instead, Justice Kennedy writes of “[t]he human toll wrought” on all people; how solitary “exacts a terrible price” on all people; and how solitary can bring all people “to the edge of madness, perhaps to madness itself.”

The most significant aspect of the concurrence therefore may not be in its explanation of the harms of solitary confinement or even in the suggestion of its unconstitutionality. Instead, the radical premise may be the suggestion that prolonged solitary confinement is unconstitutional, not only when applied to people who are particularly vulnerable or sympathetic, but to everyone.