Two Cups of Broth and Rotting Sandwiches: The Reality of Mealtime in Prisons and Jails

As paralegals with the ACLU’s National Prison Project, we spend a lot of our time speaking to and corresponding with people in our nation’s prisons, jails, and detention centers, and their loved ones. Frequently, the top concern is food. As many Americans prepare for Thanksgiving feasts with loved ones, we can’t help but think of the people we correspond with who are deprived of fresh, nutritious meals year-round.

The food in prisons and jails across the United States is too often unpalatable (the infamous “nutraloaf,” for example) and innutritious. Diets in detention also often do not meet people’s health and religious needs. For example, in 2019, guards force fed a Hindu man in ICE detention who went on hunger strike to protest the failure to provide vegan meals to him and other Hindus in detention.

Sixty-two percent of formerly incarcerated respondents to a 2020 survey reported that they rarely or never had access to fresh vegetables while incarcerated. The typical prison diet, which is high in salt, sugar, and refined carbohydrates, contributes to the elevated rates of diabetes and heart disease among the incarcerated population. People who are incarcerated in the U.S. are also six times more likely to contract a foodborne illness than the general population.

It benefits us all to ensure that people return to their communities after incarceration in better physical and mental condition than when they went in. Meals that foster diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, or other costly illnesses associated with poor nutrition result in expensive medical care for formerly incarcerated people, and a lost opportunity for them to return home in good health upon their release. Rebuilding a life after incarceration is difficult, and diminished health adds yet another barrier to reentry.

Here, we share just a few examples of what we’ve learned from our incarcerated clients about the food available in prisons, jails, and detention centers.

Jensen v. Shinn

We recently visited Lewis prison in Buckeye, Arizona to speak with our clients primarily about their health care as a part of a class action lawsuit against the state prison system. In speaking with many insulin-dependent people, we learned the food they are provided is not only deficient in nutrients but also actively harmful to the management of their diabetes. One man told us that he relies entirely on commissary foods and tries to make his own meals because the prison doesn’t offer any fresh fruit or vegetables — only refined carbohydrates, like cookies, saltine crackers, and bread.

While prison commissaries carry a broader range of foods than are available in the cafeteria for people to purchase, many incarcerated people don’t have family or friends who can fund their commissary accounts. Prison jobs — when they pay — pay an average of 13 to 52 cents per hour. This leaves little money for food, especially now with soaring inflation. And there is no special medical diet available for people with diabetes in Arizona’s state prisons.

Ahlman v. Barnes

In 2020, the ACLU filed a case on behalf of people detained in Orange County’s jails in response to unsafe conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the litigation primarily focused on issues such as testing and vaccine accessibility, many of our clients expressed that their top priority was the resumption of hot meals at the jail.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the jail stopped serving hot meals for “reasons of health and safety” according to the sheriff’s department. For more than two years, the jail served sack lunches, usually rotting bologna sandwiches, for each meal of the day. Even if the sandwiches were safe to consume, a diet of processed lunch meat can lead to serious health problems such as high blood pressure and an increased risk of heart disease and stroke. It is not only inhumane but an issue of public health. In line with our clients’ priorities, the ACLU successfully advocated for the resumption of hot meals to be included in the settlement agreement.

Duvall v. Hogan

A young man with a broken jaw was served two cups of broth for every meal at the Baltimore Jail.

After visiting our clients at the Baltimore jail in August and again in September 2022, it was clear that the quality and quantity of food provided is inadequate. We spent a lot of time in the infirmary, talking with the sickest people at the jail about the numerous failures and delays in their medical care. It was also in the infirmary where we received the most complaints about the food and not receiving enough of it — patients at the infirmary are inexplicably not allowed to order foods from the commissary at all. We spoke with a young man recovering from a broken jaw who had only been given two cups of broth for every meal. It took weeks for him to get Ensure, a nutritional shake, after he repeatedly told staff he was hungry.

In the general population, we spoke with a woman who was 17 weeks pregnant and experiencing hunger pains. She requested some snacks or extra portions. Many other incarcerated women told us they were also not getting enough food. One woman said jail staff told her they were getting small portions because they weren’t burning calories and getting activity outside of their cells.

The National Prison Project’s litigation against prisons, jails, and detention centers advocates for adequate health care and humane conditions, which includes nutrition. Aside from their constitutional right to the basic necessity of palatable and nutritious food, incarcerated people should be treated with dignity — and that includes a nutritious and healthful diet. The issue of food in prison is a moral, legal, and collective one. Sharing food and breaking bread is a fundamental part of our shared humanity — it’s why so many of our most important rituals happen around the dinner table. That humanity doesn’t go away because someone is incarcerated.

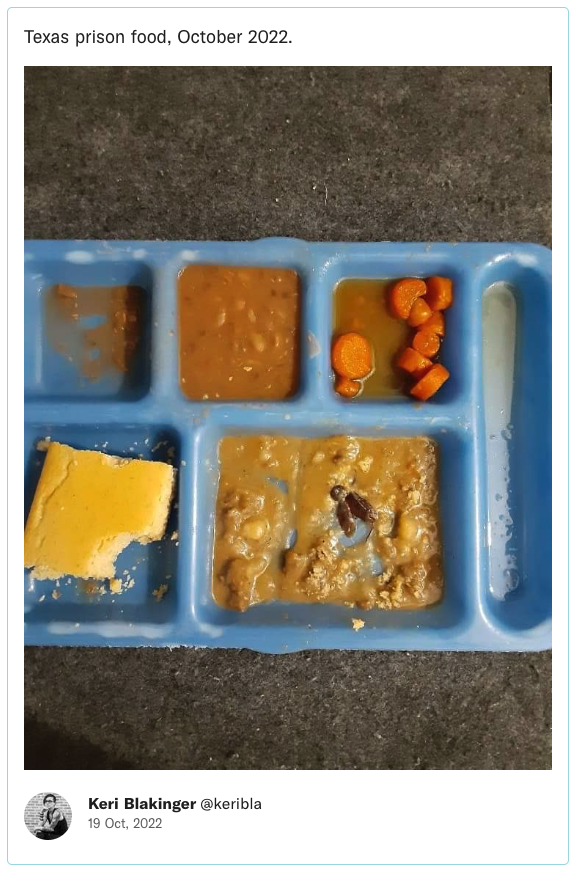

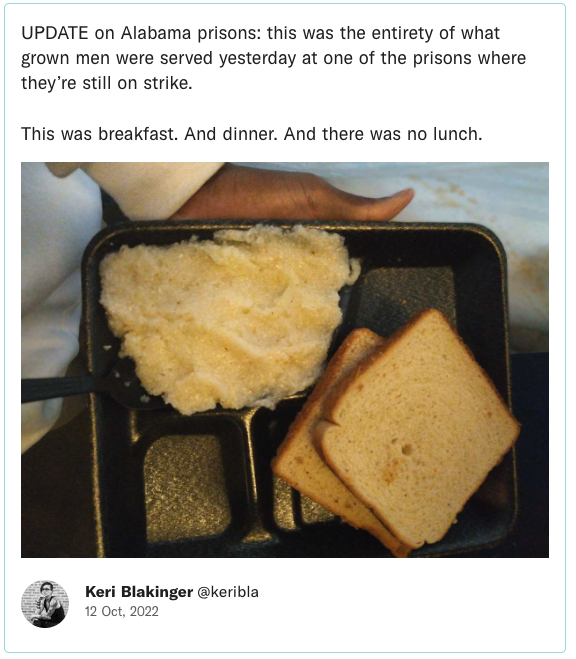

Below are more examples of the sparse, nutritionally scarce meals being served in prisons around the country: