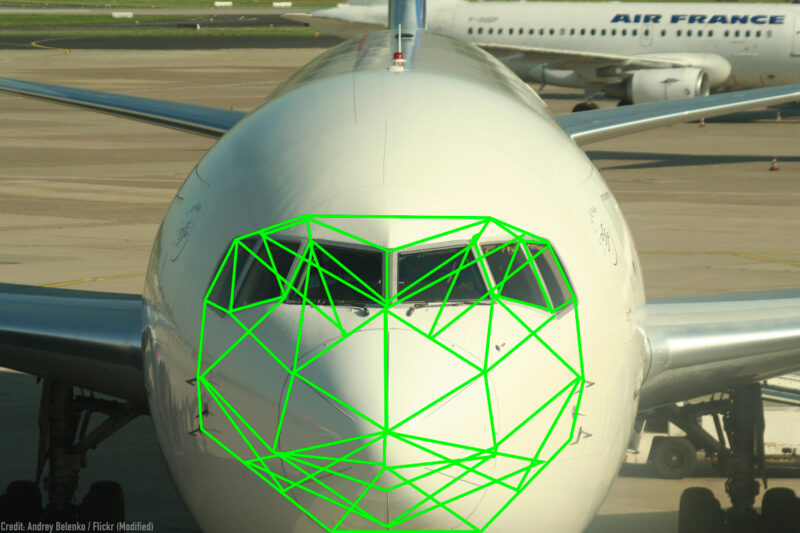

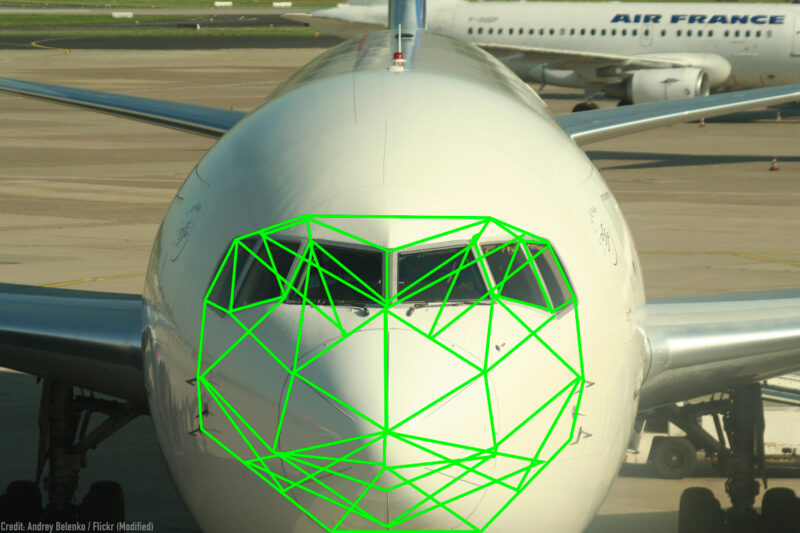

Airlines Should Decline to Participate in the Government’s Airport Face Recognition Program

Last week, we wrote about U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP)’s plans to apply face recognition to every traveler who exits the country, including Americans. One aspect of the scheme that we did not discuss was the role of the airlines. The airlines’ participation is significant because without it, the plan could not go forward, or at a minimum, its implementation would be significantly hampered.

Given their role, the airlines have a responsibility to ensure that customers’ rights are respected, yet they have not taken even some basic steps to fulfill this obligation. Until they have taken these steps—and received assurances from CBP that the agency will abide by certain privacy standards —they should not participate in these programs.

What is the role of the airlines?

CBP has launched a “Traveler Verification Service” (TVS) that envisions applying face recognition to all airline passengers, including U.S. citizens, boarding flights exiting the United States. JetBlue and Delta have been working closely with CBP on the plan. “Delta is always willing to partner with the CBP,” a Delta spokesperson said in a corporate press release that also quoted a CBP official. JetBlue, in its press release announcing its intention to “collaborate” with CBP on the program, said it hoped to “make the boarding process simple and seamless for the traveler while enhancing U.S. national security.”

According to a DHS briefing that we attended last week, the agency is still working out which tasks will be performed by airlines’ personnel—including whether the government or the airlines will own and operate the cameras that perform the face matching. In the Jetblue pilot, DHS says that the airline owns and operates the cameras, and DHS is in conversations with Delta about a similar arrangement. DHS also says the airlines do not keep copies of the photos for their own use, but that there’s nothing stopping them if they decide to start doing so.

Publicly, the airlines have largely framed their participation as an efficiency investment. JetBlue, for example, in its publicity and in uncritical media coverage, has cast the face recognition system as a matter of passenger convenience, with little mention of the program’s role in CBP’s larger biometric tracking vision. The company’s press release, for example, states that the company hopes “to learn how we can further reduce friction points in the airport experience,” with an airline executive claiming, “Self-boarding eliminates boarding pass scanning and manual passport checks. Just look into the camera and you’re on your way.”

However, customer convenience seems like a fig leaf for whatever is really going on. Given the high error rate of face recognition—especially with many passengers inevitably smiling and laughing, wearing hats, and otherwise interfering with the optimal operation of this technology—it’s hard to believe that boarding will be easier for passengers under this program than under the status quo, which involves the simple and easy act of scanning a highly reliable boarding pass barcode. CBP reports that in its tests so far the face recognition systems have had an error rate of around 4%, or 1 in 25 travelers, creating a disruptive process (disproportionately affecting African Americans and other groups) that we don’t see with bar code scans. Remember as well that the real bottleneck in loading passengers onto an aircraft takes place in the boarding bridge and aisles of an aircraft. Even if face recognition did prove to be slightly faster and easier than scanning a bar code, that wouldn’t get planes loaded any faster.

What should airlines do before further participating in the program?

Given the significant social ramifications of this program, the airlines should:

- Provide transparency to their customers and demand that DHS do the same. JetBlue’s presentation of this program as a customer convenience threatens to leave many passengers in the dark about the true scope and purpose of the face recognition infrastructure. The airlines should be more upfront with their customers. Not one of the airlines has information available on their website explaining the program, its risks, or facts about face recognition including the potential for differential inaccuracies. For example, Jetblue’s one press release on this program includes only minimal information and does not even address whether and how individuals can opt out. Airlines should include clear information to customers in advance of their flight and in writing at the terminal.

- Permit any passenger to opt out of the program. There is no clarity regarding whether and how passengers can opt out of the face recognition program. Some reporting has suggested the program is mandatory, the DHS Privacy Impact Assessment has ambiguous language, and the airlines have provided no additional information. For example, the Jetblue release suggests that only people who opt in will have their picture taken, but it’s not clear that only passengers who explicitly indicate that they would like to participate are photographed. Even if that is the policy, it’s not clear that it won’t quickly become mandatory if this program expands. When asked about this during a DHS briefing, officials said they were unsure whether travelers were informed at the gate that they could opt out of the program and suggested that non-citizens did not have this option. Given the invasiveness of this technology, all travelers should be permitted to decline participation in this program. Airlines should provide opt-out information to travelers in writing in advance, and in large signs upon boarding.

- Require clear Congressional authorization before expanding the program beyond the existing pilots: As we pointed out in our post last week, Congress has not explicitly authorized biometric exit for citizens. Congress has also not addressed the full scope of issues that come with use of face recognition, including how data should be treated. Airlines should decline to move forward with any expansion of the pilot without clear legislation from Congress—and reject any legal gymnastics DHS may employ to argue that such authorization is not needed.

- Demand assurances from DHS that customers’ rights will be protected. Last week we pointed out that a face recognition biometric exit program raises various concerns, including that data will be used for other purposes, photos will be stored for longer than is necessary, and information will be placed in the hands of CBP, a law enforcement agency that too often demonstrates a disturbing disrespect for the law. To address these concerns, airlines should demand that any data collected be purged in a timely fashion and not used for other purposes. In addition, they should ensure that CBP does not use the data to take agency actions that raise civil rights concerns, and puts in place a robust complaint system to address violations of such policies.

- Promise not to leverage this program for data collection. The precise operation of this program has not yet been settled upon, including whether the airlines will own and operate the cameras. As The Identity Project points out, the program will give airlines the chance to compile photographs or other data from passengers that they can’t now collect. CBP should ensure that can’t happen. If it doesn’t, the airlines should pledge not to retain any photographs of travelers, let alone use them for any other purposes, and should make such a pledge in legally binding privacy policies.

- Agree to bear the cost of face recognition mismatches. What if someone gets pulled out of line or even misses their flight because of a face recognition matching failure? It hardly seems fair to make the individual pay the price for capricious and unpredictable failures by this inaccurate technology. Airlines should make clear to customers that they will compensate customers for any inconvenience caused by a face recognition error.

Stay informed

Sign up to be the first to hear about how to take action.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.

By completing this form, I agree to receive occasional emails per the terms of the ACLU's privacy statement.