A company called EarthNow has announced an ambitious effort to create a service that will provide a live satellite video feed of any spot on earth. As reported on Friday by Mic, the service amounts to a live, real-time version of Google Earth (though Google is not involved). It’s not clear how realistic this is, but the concept is a scary one for privacy.

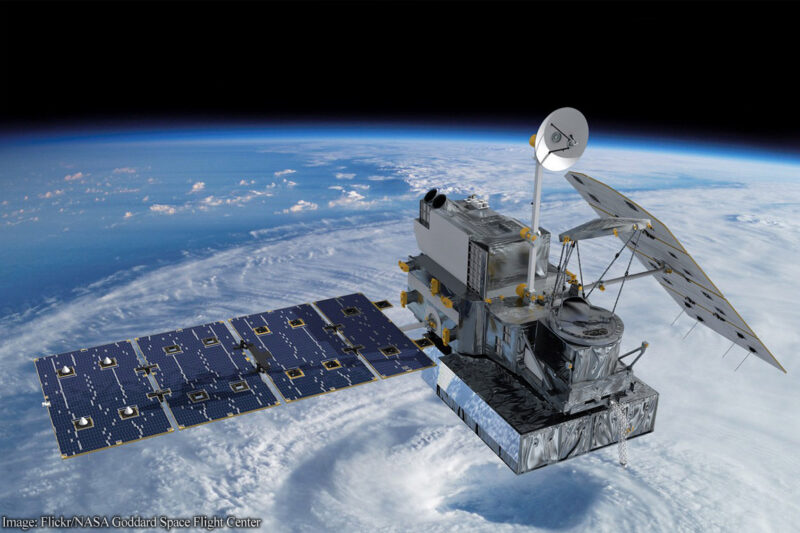

In its press release, EarthNow says its intent is “to deploy a large constellation of advanced imaging satellites that will deliver real-time, continuous video of almost anywhere on Earth.” The company says it will achieve this by using “the World’s first low-cost, high-performance satellites for mass production.” It says that it has secured a first round of financing from several major investors.

The company is vague about two crucial questions about the service: What the resolution will be, and who will have access to the video? On the first, the company does seem to suggest at least a certain degree of resolution in the uses it cites for its service, such as “helping ‘smart cities’ become more efficient,” “observing conflict zones,” and “catching illegal fishing in the act.” We don’t know exactly what the company’s satellites would be able to see, but clearly it’s at least street-level detail.

On the question of who would have access to the company’s video, EarthNow’s press release says that initially the company “will offer commercial video and intelligent vision services” to “a range of government and enterprise customers.” Eventually, however, the company says that it plans to create “mass market applications that can be accessed instantly from a smartphone or tablet.” I’m not sure what’s worse: having such a powerful surveillance tool exclusively available to government agencies and big corporations or having it available to any friends, neighbors, or internet creeps who want to see what I’m doing. The latter would be worse in some ways, though at least the surveillance wouldn’t be secret, and everybody would quickly come to learn how exposed they are so they could adjust their behavior.

Either way, if this actually came to pass, it would be a privacy disaster. It’s not just that video of our homes and every other spot on earth would be susceptible to monitoring by unknown parties at any time, with no way to know whether and when such monitoring is underway. It's that the video could also be stored and subject to analytics of all kinds — what EarthNow refers to as “intelligent vision services.” In addition to video of our front yard, for example, computers could be programmed to sound an alarm whenever someone walks out of our house or enters it. And it could automatically track where we go from where and with whom. There would no longer be any place on earth where one could feel truly alone — no beach or yard in which to sunbathe or cavort with friends; no tall grass or secluded roof deck to make love on; no mountain or wilderness trail on which to seek solitude or time with a friend. There would be no place where one could feel secure that someone was not monitoring and recording from the sky.

There is good reason to think that the American people don’t want to live under such a system. Consider:

- In 2016, the public learned that the police in Baltimore had engaged a company called Persistent Surveillance Systems to implement an aircraft-based wide-area aerial surveillance system that was capable of recording a 30-square-mile area and tracking every pedestrian and vehicle in that area and where they traveled. That revelation led to an uproar in Baltimore and around the country, and the police put the trial on hold. No other American cities have implemented the system since. What EarthNow is proposing would essentially be a global version of the Baltimore experiment.

- When Americans realized a few years ago that the technology for surveillance drones had arrived and was no longer science fiction, we saw a rapid and amazing outpouring of concern in most state legislatures around the country. Since 2013, 44 states have enacted laws or resolutions on drones, a large proportion of which impose restrictions on the use of drones for surveillance.

- Perhaps the most direct comparison to the EarthNow proposal was a 2007 plan approved by the Department of Homeland Security to allow U.S. law enforcement agencies to use the nation’s powerful spy satellites domestically. The ACLU strongly objected to this program, which was run by a blandly named entity called the “National Applications Office.” Of all the significant post-9/11 privacy controversies that were raging at the time — illegal NSA spying, data mining, new airport searches, and many others — this proposal seemed to offend members of Congress especially deeply. The House Homeland Security Committee held a hearing, members reacted very strongly against the proposal, and DHS soon thereafter announced that it was shutting down the program.

We should expect that however the EarthNow effort may fare, it will become increasingly feasible in the coming years to create the capability that this company is contemplating. As a society, we should make a conscious choice not to go there. We should not let technological capability dictate what we actually deploy, just as we have made a conscious choice (through our wiretapping laws) to generally disallow surveillance cameras in public places from including microphones. It is true that blanket aerial surveillance could be implemented by other governments or by companies operating out of other countries, and that is a problem that we may have to confront. But we can start by deciding for ourselves a national goal to avoid such surveillance.

We actually already have at least one policy tool with which we can start to enforce such a decision: a 1992 law that regulates the filming of earth from space. When Space X launched into space and live-streamed video of Elon Musk’s Tesla being shot off into space, the company was taken to task by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which is charged with enforcing that law.

The ACLU defends the right to photography under the First Amendment, but I don’t think such a right would extend to space. Going to space is, at least for the foreseeable future, the exclusive province of governments and corporations. The former has no free expression rights, and such rights are greatly reduced for the latter — especially given that space is already an extremely highly regulated arena. Photographer’s rights are something that exist when the photographer is in a place where he or she has a right to be, but space (for the foreseeable future) is not such a place. Besides that, the public interest in preventing this kind of blanket aerial photography of our lives is compelling.