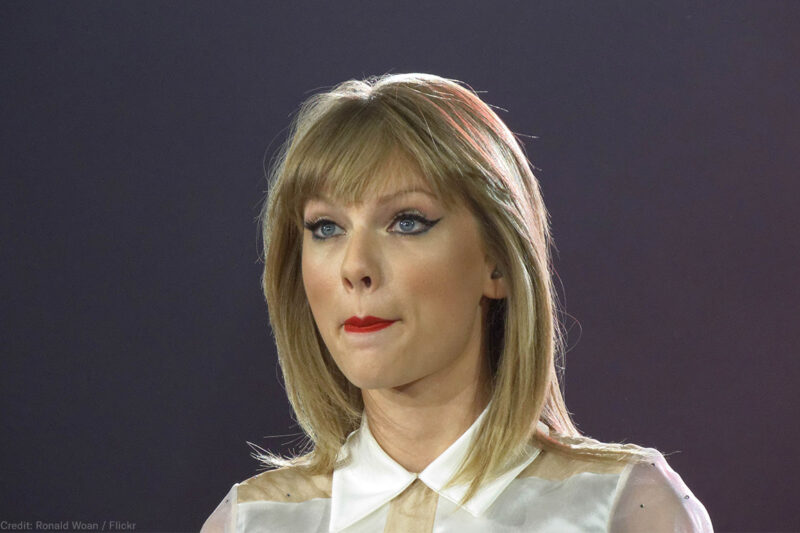

Rolling Stone reported this week that face recognition was used on attendees at a Taylor Swift concert in Los Angeles to look for stalkers. Stalkers are a real problem, and we sympathize with how scary it must be for a celebrity to know that they are out there. Nonetheless, we have a number of concerns about where this goes.

We already know this technology is starting to be deployed in sports stadiums and retail stores. This is an enormously powerful surveillance tool — something that has never before been seen in the history of humanity, and something that we shouldn’t rush into embracing without checks and balances to make sure it’s not abused.

One set of questions concerns what, if anything, was done with all the photos that were collected at the Taylor Swift concert. Were they saved? Will they be shared with anyone or used for marketing purposes? Will the security people use them for tracking people’s movements and behavior and flagging those who are supposedly “suspicious”? These are the privacy issues that affect every concertgoer here and in any future uses of the technology.

Another issue is the matter of notice. In this case, security staff essentially tricked concertgoers into presenting a clear frontal view of their faces by setting up a kiosk playing a video of concert highlights, with a camera that captured the faces of those who stopped to gaze at it.

The officials at the concert venue should have told people that their faces would be scanned for security purposes — preferably before they paid for a ticket. They also should also have told attendees whether they were saving the photos and what they were planning to do with them. If concert officials didn’t think people would mind, there’s no reason they shouldn’t have done so. If they did think that their customers would mind, but did it anyway, that’s pretty shady. Security people are used to operating with secrecy, but this is a novel, controversial, and very powerful technology, and people have a right to know when they’re being subjected to it.

Then there are the perennial questions about the accuracy of this technology, which is questionable. If there’s a match between concertgoers and suspected stalkers, how would those people be treated? Would security agents treat them as dangerous, or would they be treated with respect until a speedy and fair verification process is completed?

Regardless of how this technology was implemented in this one situation, we know that as it is rushed into deployment by lots of different operators, it’s often not going to be done right.

Finally, one of the biggest concerns here is fairness and due process around private watchlists. Face recognition is of little use as a security tool unless there’s a watchlist to back it up — a set of photos of people that you’re looking out for. With any watchlist, the questions are who is put on those lists and based on what information? Are the people listed told that they’re being included? Are they given an opportunity to appeal their listing?

Certainly a private property owner can order anyone they want to leave their property, and at least as of now, there’s no law preventing them from setting up a face surveillance system to make sure they don’t come back. But as these watchlists become institutionalized, and in all likelihood shared, the consequences of unfair treatment or racial bias in the compilation of these lists become magnified.

Today, if you are treated badly by a store clerk, and you stand up for yourself and get in an ugly argument, the worst thing that’s likely to happen is you feel rotten for a while. But with today’s technology it’s not hard to imagine a store clerk entering a photo of your face from surveillance cameras into a watchlist so that you’re approached by security when you try to shop there again — and maybe at any of that company’s stores across the country, or at places run by corporate partners of that store, too, including perhaps concerts, sports stadiums, malls, and who knows where else.

For one thing, that means that you’re less likely to stand up for yourself, because that clerk now wields enormous power over you. Power has been shifted from customers to companies and their employees. It also means that the consequences have become greatly amplified for those who are blacklisted unfairly.

There’s a long history of private and quasi-private watchlists being abused, going back to the labor battles of the early 20th century, when workers and organizers were blacklisted as “troublemakers” and could have trouble getting a job. And the government’s nightmarish system of watchlists continues to be riddled with Kafkaesque problems even after years of reform efforts as well as checks on the government like the Privacy Act and the Fourth Amendment, which don’t apply to private companies.

We understand the importance of protecting someone like Taylor Swift against the dangerous people that are unfortunately out there. What we don’t want to see is companies turned into stalkers themselves, following our every move just because a technology has come along that makes that possible.

Sign up for the ACLU’s Best Reads and get our finest content from the week delivered to your inbox every Saturday.