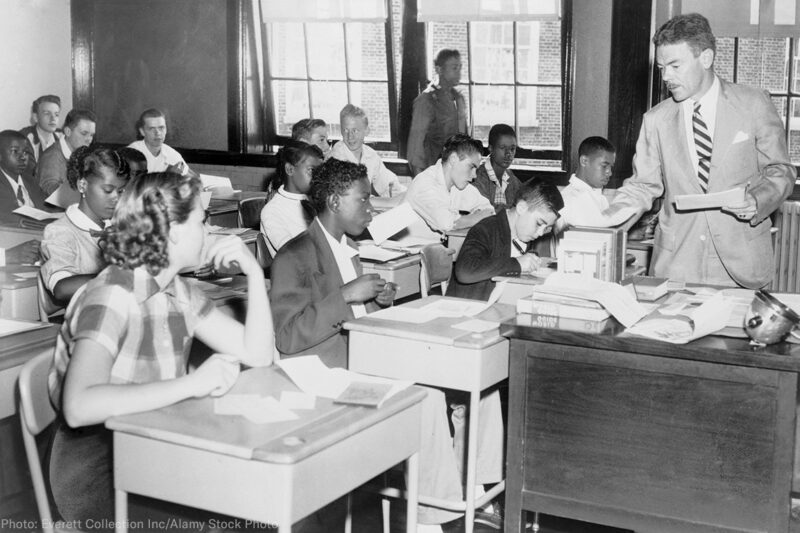

It’s been 64 years this week since Brown v. Board Of Education began charting a new course for public schools and race in America. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court struck down the dishonest doctrine of “separate but equal” and exposed the white supremacy that lay beneath it.

Yet, the celebration this year is muted by a fresh sense of uncertainty. The sanctity of the landmark decision that helped ensure Black children’s full and equal access to participation in American society is increasingly under attack in the courts, in government, and in the private sphere.

Although there has always been some level of disagreement about what Brown means and exactly what it requires, its vital importance in American jurisprudence has been firm. Even President Dwight D. Eisenhower, an incrementalist and certainly a racist by today’s standards, eventually admitted of the decision: “… there can be no question that the judgment of the court was right.”

Indeed, Brown has for decades been given its due respect by people on all sides of the aisle — until now. Wendy Vitter, nominee for the United States District Court in Louisiana, for one, refused to express an opinion on whether Brown was correctly decided, sparking widespread media coverage.

Vitter’s refusal to endorse the Brown decision stands alongside many years of indications that the nation has lost sight of the case’s importance. In overruling the late 19th-century case Plessy v. Ferguson, which upheld segregation in Louisiana streetcars, the Supreme Court did more than just address who sat next to whom in American schools. It also served as the inspiration for efforts to end restrictions in public accommodations and in housing and to assure access to the voting booth.

Brown’s significance also went beyond the nation’s borders. During the 1950s, the United States was embroiled in a Cold War with the Soviet Union. While U.S. leaders correctly saw Soviet forces as enemies of freedom, the world was watching as America hypocritically enforced the cruelties of apartheid on even its youngest citizens.

The Truman Administration laid the dilemma out plainly: “The existence of discrimination against minority groups in the United States has an adverse effect upon our relations with other countries.” By addressing school segregation through Brown, the United States addressed the dissonance between its desire to be seen as a proponent of human rights and its denial of those rights to the descendants of people it had enslaved.

After a period of fierce resistance to integration, Brown catalyzed progress in desegregating schools in the southern states, the sites of most of the early school desegregation cases. But enforcement of the order finding that segregation had harmed Black children “in a way unlikely ever to be undone” has been difficult. In recent years, court decisions have eroded the hard-fought progress in the South spurred by the Brown decision six decades ago. For example, researchers studied more than 200 school districts that were released from court-ordered desegregation plans between 1991 and 2008 and found them more likely to have increased segregation than schools that stayed under court oversight.

Up North, segregation continues to be a reality in far too many schools as well, and groups like the Pacific Legal Foundation would like to keep it that way. The law firm is bringing a challenge to remedies in the ACLU lawsuit Sheff v. O’Neill, a groundbreaking, decades-long case that has reduced racial segregation in public schools in Hartford, Connecticut, and has become a model for desegregation efforts across the country. To protect the legacy and future of the community’s school integration efforts, the ACLU earlier this month joined the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. and the Center for Children’s Advocacy in filing a motion to intervene.

From the threats to reverse the hard-fought gains in the Hartford area, to the white fear that summons police to detain innocent Black people in a Starbucks, it’s clear that Brown’s vision of a country where everyone, regardless of race or ethnicity, can enjoy equal access to spaces has yet to be realized.

Sixty-four years after Brown, the world is again watching to see whether the United States will walk the walk of equality that it has talked about, but ignored, for so long. History will judge us by our courts’ willingness and each of our efforts to ensure that children suffering the harmful consequences of segregation will get the same opportunities to learn as their white peers. This is the time to work toward true equality and justice. It’s not the time to roll back the progress that America has made – and has the potential to make — thanks to Brown.