In the spring of 1958, civil rights leader and future Georgia Congressman John Lewis met Jim Lawson, an organizer with a nonviolent organizing group called the Fellowship Of Reconciliation (FOR). Lawson introduced Lewis to the FOR's popular comic book The Montgomery Story, which provided a compelling graphic narrative of the Montgomery bus boycott, as well as an accessible outline of FOR's broad ethic of nonviolent civil disobedience. Lewis has recently described the comic as a "Bible" and "guide" for Southern civil rights organizers of the time—an invaluable source of both emotional inspiration and practical guidance to the growing family of nonviolent resistors.

Fifty-six years later, Lewis is hoping that his new graphic memoir March can provide a similar stimulus to a new generation of civil rights activists—the "past and future children" of the movement, as he refers to them in the dedication page. March is an autobiography in three parts, and Book One was released in August 2013. Books two and three are forthcoming, and a release date has not yet been set for either of them. Book one focuses on Lewis's upbringing in Pike County, Alabama and follows his evolution as a civil rights leader, especially as a participant in the Nashville food counter sit-ins of 1960.

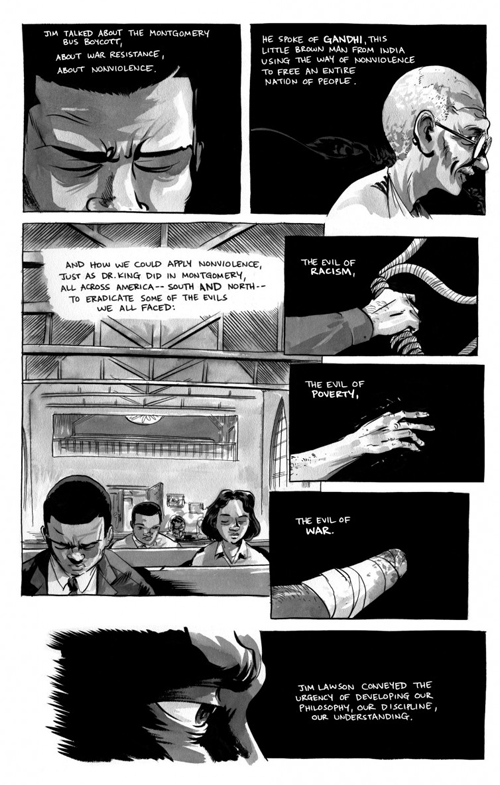

March is a much longer narrative than The Montgomery Story, allowing it to both meaningfully testify to the lived experiences of Lewis and other activists while depicting in detail the overarching strategies and philosophy of the movement. Much of this is accomplished through the creative choices of illustrator Nate Powell, who excels at visually emphasizing the story's most important and heart-wrenching moments. Powell often utilizes broad, eye-catching images that transcend traditional panels and free small pieces of text to speak more loudly. His accessible and innovative artwork underscores the great potential of graphic novels to communicate deeply and directly to diverse audiences.

However, while March is perhaps the exemplar of recent graphic novels that bring civil rights and racial justice issues to light, it is far from the only one. In February, Marvel comics released issue 1 of Ms. Marvel, a new series about a 16-year old Pakistani-American teenager who develops superpowers. While Ms. Marvel has been perhaps the most high-profile step forward in integrating and even foregrounding racial justice issues into the comic book world, she too is not the first. She was preceded by countless, less successful twists on traditional comics' lore, many of which were printed by DC Comics' short-lived Milestone Comics imprint. Milestone, created in 1993 to address a lack of diversity in the DC universe, introduced the popular African-American teenage superhero Static, as well as more experimental works such as Blood Syndicate, a series about multiracial gangsters who develop superpowers after being mutated by experimental police teargas. Static and Blood Syndicate were also two of the first mainstream superhero comics to feature openly gay characters.

A number of artists have also released important graphic works in the last 10 years that deal more explicitly with black history and contemporary civil rights issues. Vertigo's Incognegro follows a light-skinned Black reporter in the deep south who must pass as white to investigate his brother's arrest. The book was inspired by the real-life experiences of Walter White, former head of the NAACP, who went undercover to report on lynchings. Kyle Baker's Nat Turner has also been critically acclaimed for its graphic depiction (in form and content) of the 1831 slave rebellion that provoked a wave of strengthened social control over slaves in Antebellum America. The New Press has even recently reissued in graphic form its 1999 study on mass incarceration and racial disparities, Race to Incarcerate.

Read in the context of this exciting and growing body of graphic work, one must be hopeful that March will broaden the public's familiarity with the lives of Congressman Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr., and the countless other men and women of the Black freedom struggle. And it is through such exciting and innovative art that we might move closer to Congressman Lewis' wish to "imbue people with something – the young, the very young, and those not so young, [to] be ready to go out there, and push and pull."

Learn more about Black History Month and other civil liberties issues: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.