Last week, two different sources within two days’ time voiced a very similar message about race. Both the timing and the message are particularly welcome.

“Forward through Ferguson: A Path Toward Racial Equity,” a report issued by a committee established by Gov. Jay Nixon pursued a mandate to understand the “path to toward racial equity” by focusing on the broad, interconnected factors which set the stage for the Mike Brown shooting and its aftermath last August. In a newsroom far away, Ta-Nehisi Coates explored the roots of mass incarceration in his prolific examination of race, “The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration,” which appeared in The Atlantic’s October issue.

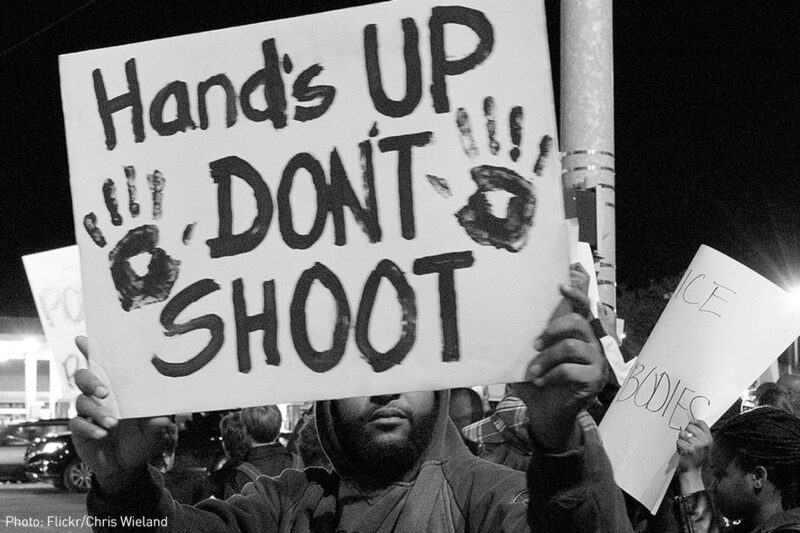

To understand why the events in Ferguson unfolded the way they did or why the United States incarcerates more people than even the most repressive countries in the world, the Ferguson Commission and Coates both acknowledge that much of the current discourse fails to take into account the complex collection of structural causes of the problems we face today.

In the report, the Ferguson Commission faulted past commissions for focusing on economic issues “to the exclusion of social issues, such as racial tension, segregation, and discrimination” in the incendiary aftermath of police violence against Black people. In taking an “unflinching” look at the problems facing the St. Louis region, the commission concludes that responses to systemic to racial discrimination are root causes of the violence seen in the area. The report also recognizes that the type of discrimination with the greatest impact is structural and not the result of actions of biased individuals and that “our institutions and existing systems are not equal and . . . [and] ha[ve]racial repercussions . . . when it comes to law enforcement, the justice system, housing, health education, and income.” Although the report offers specific suggestions dealing with discrimination in each of those areas, the ultimate message is the need to attend to structural problems writ large: “[I]f the people engage with it —discuss, debate and argue about it — there is a much greater chance that the call to action presented here will be implemented.”

Coates, likewise, states that America’s toxic incarceration rates are the result of deep-seated prejudices and stereotypes about race and criminality, which were catastrophically combined with a refusal to acknowledge and address the role that racism played in the growth of prisons in the United States since the mid-1970s. Coates refers to Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s 1965 report “The Negro Family” as being an unintentional illustration of the causes of the frenzy for mass incarceration that occurred starting in the ’60s. While acknowledging that Moynihan identified legitimate concerns surrounding violent crime and family breakdown in inner cities, Coates points out that politicians and policy makers cherry picked the sections of his report they needed to justify state coercion and punishment not government responsibility and uplift.

While trumpeting the alleged role of the “broken black family” in crime, people conveniently ignored those parts of the report decrying the role of the nation’s history of crippling discrimination in creating the conditions that lead to violence: “That the Negro American has survived at all is extraordinary …,” wrote Moynihan, “[b]ut it may not be supposed that the Negro American community has not paid a fearful price for the incredible mistreatment to which it has been subjected over the past three centuries.” Instead, they perverted Moynihan’s argument to justify draconian criminal laws that would soon erect “The Gray Wastes — our carceral state, a sprawling netherworld of prisons and jails —” that now incarcerate 25 percent of the world’s prison population, disproportionately Black and poor.

Ultimately, both the Ferguson Commission and Coates are united in expressing the need to go beyond addressing specific polices whose impact is strongly felt by communities of color. As Coates eloquently states “[a] serious reform of our carceral policy . . . cannot concern itself merely with sentencing reform, cannot pretend as though the past 50 years of criminal-justice policy did not do real damage . . .[I]t is not possible to truly reform our justice system without reforming the institutional structures, the communities, and the politics that surround it.”

Whether we will be reading new versions of the Ferguson Report in 25 years will depend in part upon whether we heed its call to consider structural changes now.