Dennis D. Parker is Director of the ACLU's Racial Justice Program which advocates for racial justice using litigation, public education, community organizing and legislation. Prior jobs include Chief of the New York State Attorney General’s Civil Rights Bureau, and staff attorney at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. He publishes and lectures extensively about civil rights and is an adjunct professor at New York Law School. He graduated from Middlebury College and Harvard Law School.

We are again in the season during which we recognize the accomplishments of African-Americans who have contributed greatly to the life of the nation. Putting aside whether it makes sense to limit the observance to a once a year, it is important to acclaim those people who overcame seemingly insurmountable obstacles in order to distinguish themselves and make it possible for the United States to come closer to achieving its loftiest aspirations. One of the most important things that each of the people we honor this month did was to open doors of opportunity for everyone, people of color and whites alike. But in honoring those people, we have to be mindful of the need to make sure that doors remain open for future generations, lest we find them closed again, either because of a gradual, almost imperceptible closing or a sudden slamming.

Civil rights workers sacrificed everything, including their lives, to secure rights for people who had been told that they had no rights by everyone from the nation's highest court to people on the streets. Scientists who would have been denied admittance to many of the nation's schools or entry to its hospitals invented, pioneered and assisted in changing the medical and technological landscape of the nation. Athletes excelled and set records in sports from which they were barred not very long before.

With a collection of civil rights laws on the books, people of color are in government and business positions which would have been unthinkable just a few generations ago. A sizeable number of people of color are in the middle class (and even some upper class), and, most extraordinarily, an African-American man is in the White House. It is tempting to kick back and celebrate, to pat ourselves on the back for our progress and achievement.

For far too many African-Americans, the nation's aspirations remain a dream deferred. In The New Jim Crow, Professor Michelle Alexander traces how the astronomical increase in the American prison population, fueled in large part by draconian sentences for nonviolent drug offenses, has had a particularly large impact on African-Americans. Alexander chronicles how the impact isn't limited to time spent in jail, upon release, the African-American prisoner can expect to face the kind of lack of access to jobs, education, and housing that characterized the era of segregation laws. More ominous are the impacts of the high incarceration rates that are felt not only by the incarcerated individual, but which have the effect of tearing families and communities apart.

The list of exclusions from the American dream is not limited to those who have had contact with the criminal justice system. In too many facets of American life, the chasm between African-Americans and whites persist. Throughout the economic crises, African-Americans have been hit particularly hard. Despite apparent improvements in the unemployment rate, African-American unemployment remains nearly double than that of whites. African-American foreclosure rates were double those of whites, little surprise given the studies showing that, even controlling for income and assets, that African-Americans were far more likely to be given subprime and predatory loans than whites. Ironically, as reported in the New York Times, even the process of going broke is harsher for African-Americans. A study from the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies documents that, even adjusting for income, homeownership, assets and education, African-Americans were twice as likely to be steered into more costly and onerous forms of consumer bankruptcy. Whether speaking about increasingly harsh school discipline or the likelihood of being called back for a job interview, study after study demonstrates that even when nonracial factors are controlled for, African-Americans fare far worse than whites.

Even those African-Americans who have done well financially have a far more tenuous grasp on the American dream than do whites. One of the seldom-heeded stories of the economic crisis has been the story of its devastating impact on the African-American middle class. An alarming report by the Pew Research Center in July 2011 described how the median wealth of white families is nearly 20 times that of African-American families and that the disparity is twice what it had been over the preceding 20 years. More than a third of African-American families, compared to 15 percent of white households had zero or negative net worth. Much of this disparity can be accounted for by the fact that African-American wealth tends to be more concentrated in homeownership.

This daunting list of continuing problems facing the African-American community is not intended to throw a wet blanket on the month's celebrations. It is instead a call to action. We should resolve to continue the work started by those who fought for equal opportunity for themselves and others. In the end, the best way to honor our heroic African-American predecessors is not through the naming of streets or the erection of monuments, but by making sure that the doors are open for future generations to have the opportunity to emulate and build upon their achievements.

This blog post is one of several personal testimonials written by ACLU staff members to commemorate Black History Month.

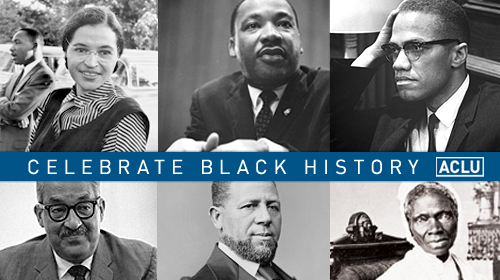

Do you know who’s pictured in our Celebrate Black History logo? Top row, from left to right: Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. Bottom row, from left to right: Thurgood Marshall, Hiram Rhodes Revels and Sojourner Truth.

Learn more about racial justice: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.