Lawsuit Challenges Discriminatory Housing Policy in Chesterfield County, Virginia

Housing discrimination takes different forms in different eras. More than fifty years after the passage of the Fair Housing Act (FHA), it’s rare to see an advertisement for housing that says “Whites Only.” But in Chesterfield County, Virginia, where a Black resident is almost three times as likely as a white resident to have a criminal record, an explicit policy barring any individual with a conviction from housing has a similar effect.

Sterling Glen is an apartment complex in a white neighborhood in Chesterfield County. Since at least 2017, Sterling Glen has explicitly stated on its application that no person with a felony conviction, regardless of how long ago it was, can live there. It also bars applicants with many kinds of misdemeanor offenses, including drug convictions. Bans like these not only pose a barrier to those reentering the community after incarceration, but those with records who have been living and working in the community for years or even decades. A lack of access to permanent housing can also increase rates of recidivism, perpetuating cycles of criminalization and ultimately making communities less secure.

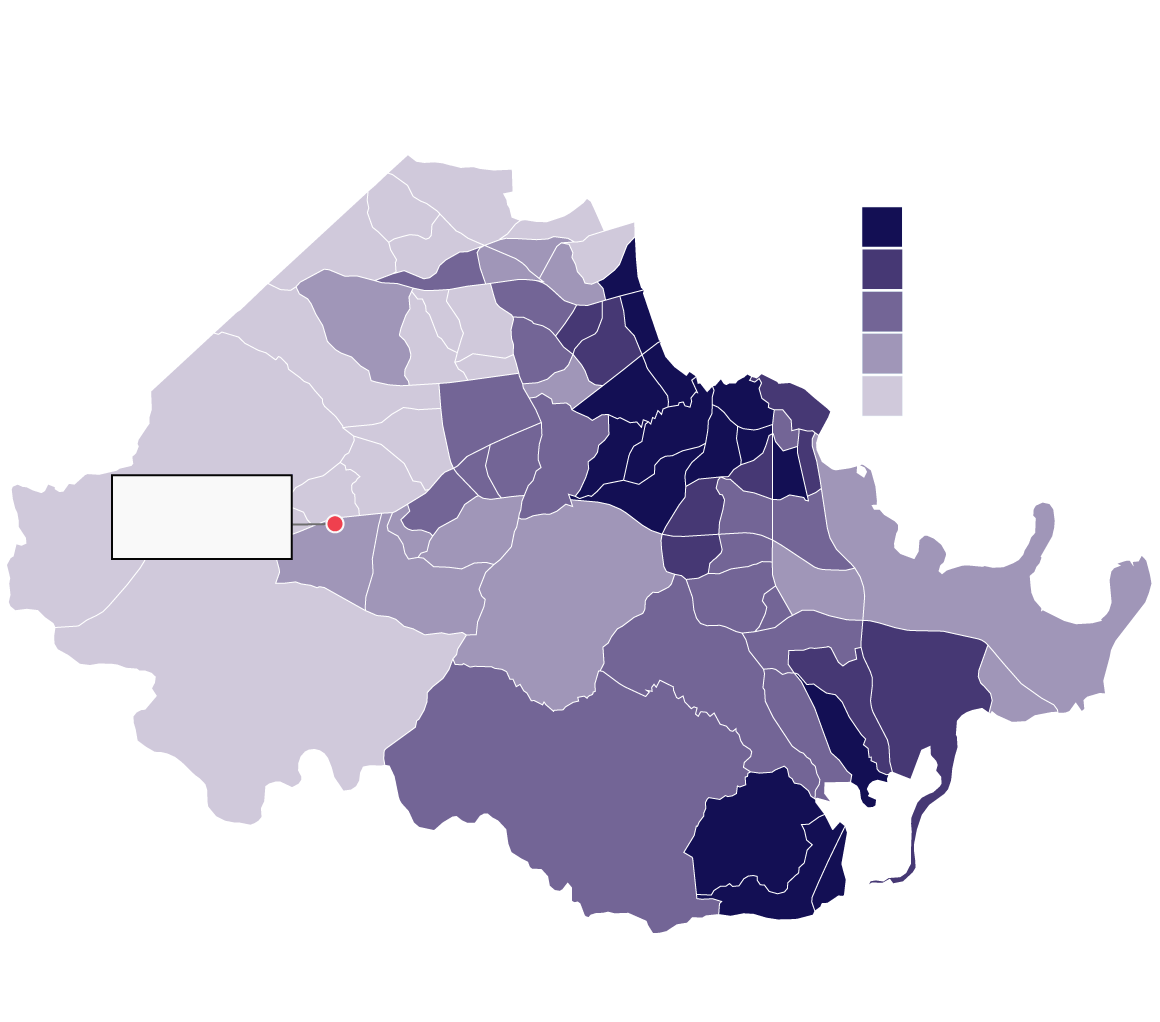

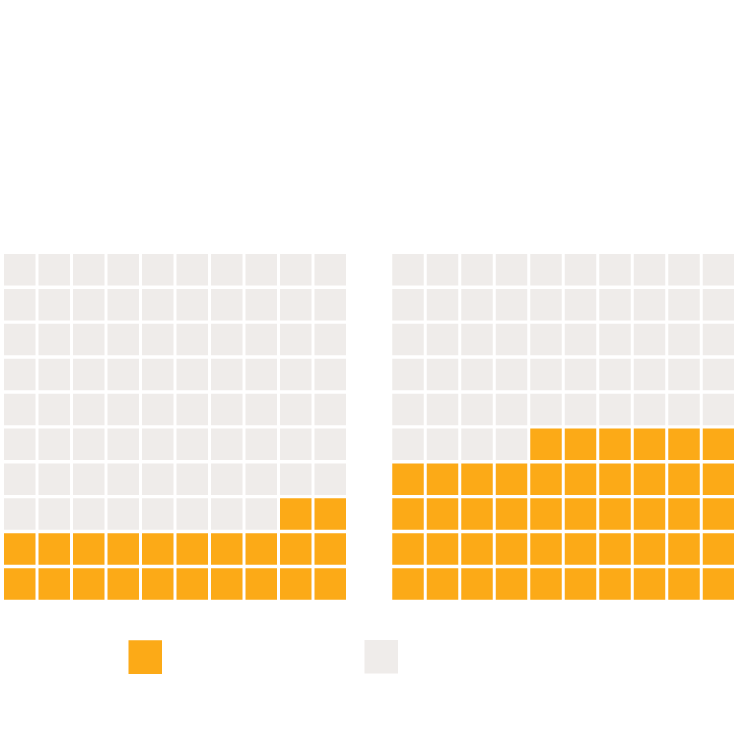

Chesterfield County, Virginia

Sterling Glen’s housing policy discriminates against Black renters

in a mostly white area of Chesterfield County

Percentage Black Pop.

35 - 89% Black

20 - 35%

15 - 20%

10 - 15%

0 - 10%

Sterling Glen

Apartments

Note: By census tract

Source: 2010 Decennial Census; virginiacourtdata.com

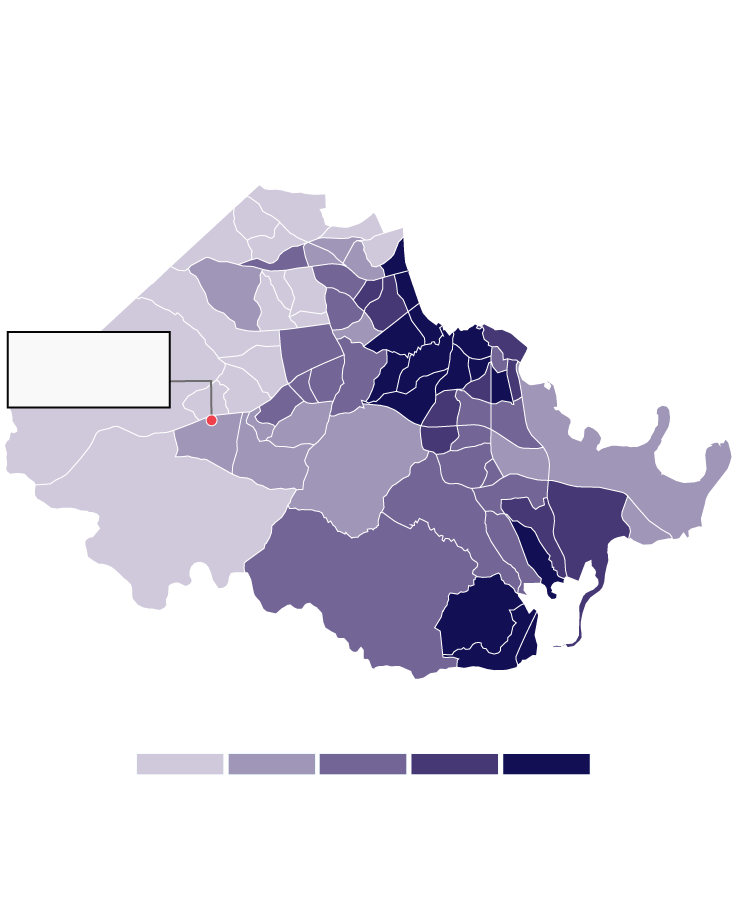

Chesterfield County, Virginia

Sterling Glen’s housing policy discriminates

against Black renters in mostly White area

Sterling Glen

Apartments

Percentage Black Pop.

10 - 15%

15 - 25%

25 - 35%

35 - 89%

0 - 10%

Note: By census tract

Source: 2010 Decennial Census; virginiacourtdata.com

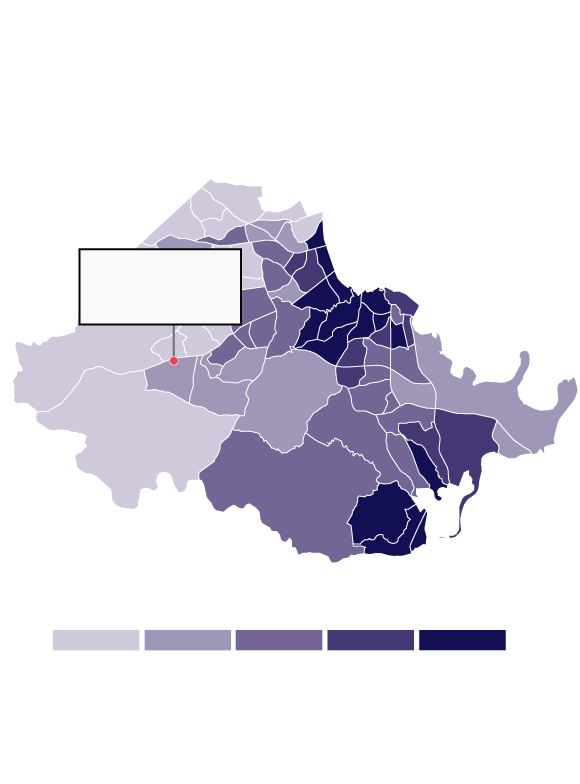

Chesterfield County, VA

Sterling Glen’s housing policy

discriminates against Black renters

in mostly white area

Sterling Glen

Apartments

Percentage Black Pop.

10 - 15%

15 - 25%

25 - 35%

35 - 89%

0 - 10%

Note: By census tract

Source: 2010 Decennial Census; virginiacourtdata.com

<!--*/

*/

/*-->*/

These numbers mirror national trends. As a result of our country’s bloated criminal justice system, more than 625,000 individuals are released from prison each year. Nationally, approximately 19 million people have at least one felony conviction and 100 million people, nearly one-third of the population, have a criminal record. But the impact of criminal convictions is not evenly distributed throughout the population.

People of color are disproportionately represented at every stage of our criminal justice system, including among those with criminal records. As a result, any policy that excludes people with criminal records from housing disproportionately harms people of color. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has recognized that excluding people with criminal records can be considered race discrimination under the FHA because “African Americans and Hispanics are arrested, convicted, and incarcerated at rates disproportionate to their share of the general population.”

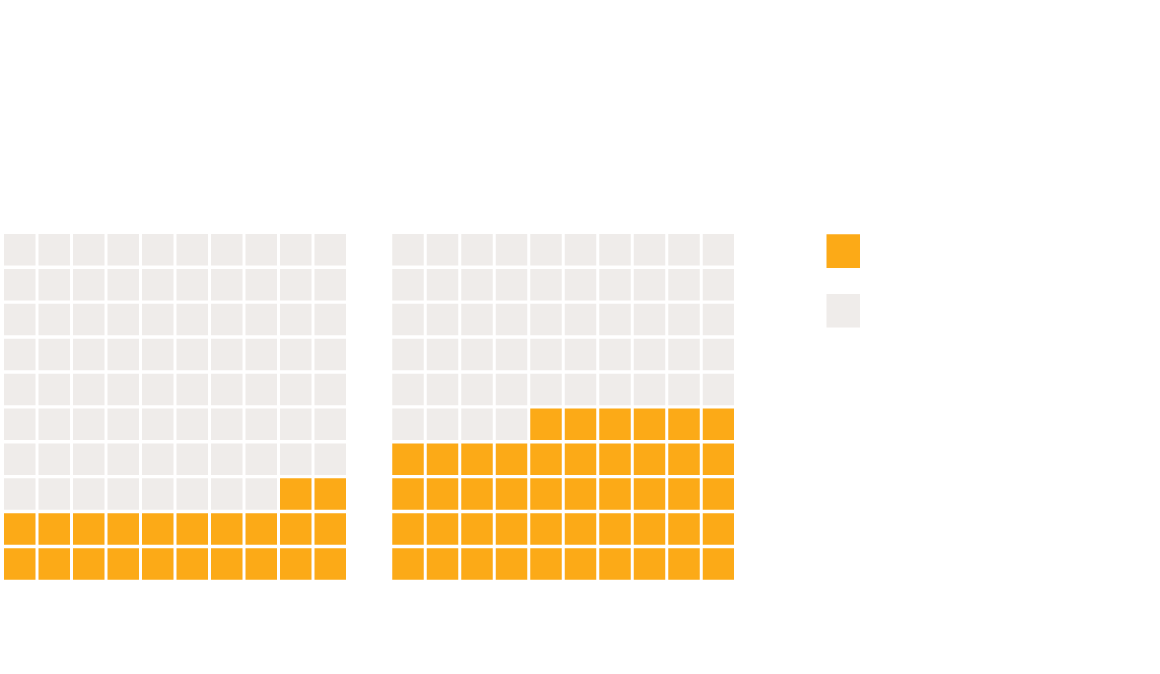

In Chesterfield County, individuals who are Black represented 46% of those convicted of a felony between 2007 and 2017, despite only accounting for 22% of the population. Put another way: there are 23 people with a felony conviction per 1,000 white people in Chesterfield County, but 65 people with a felony conviction per 1,000 Black people in the same geographic area.

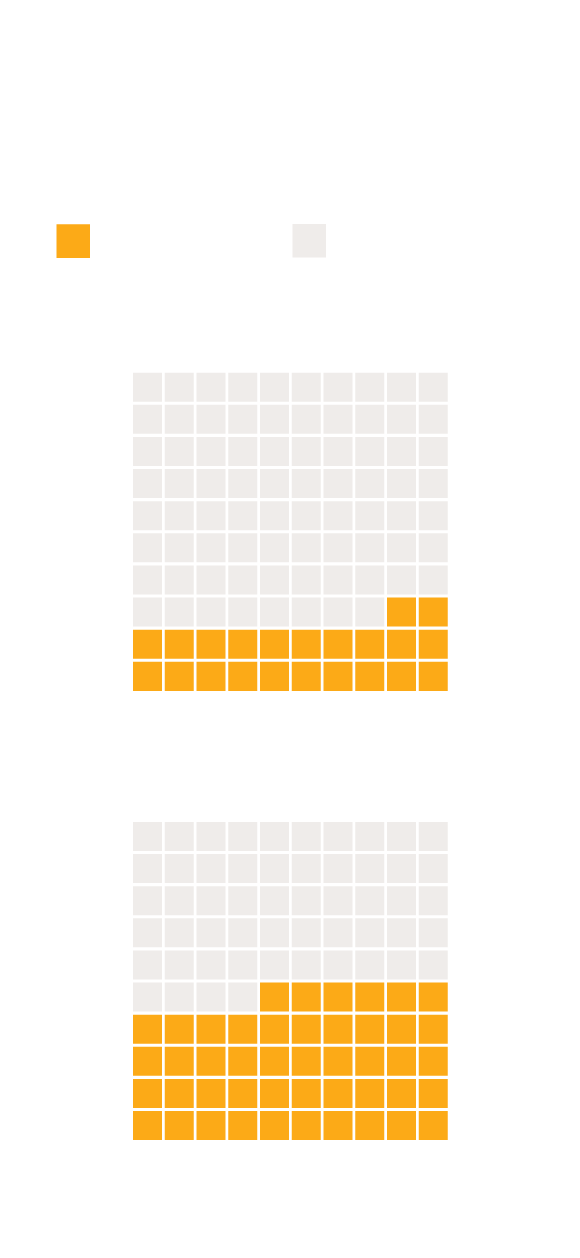

Black People Make Up 22% of Chesterfield County

Population, but 46% of People with Felony Convictions

Population

People with Felony

Convictions

Black people

Non-Black people

Source: 2010 Decennial Census; virginiacourtdata.com

Black People Make Up 22% of

Chesterfield County Population, but

46% of People with Felony Convictions

Population

People with Felony

Convictions

Black people

Non-Black people

Source: 2010 Decennial Census; virginiacourtdata.com

Black People Make Up 22% of

Chesterfield County Population,

but 46% of People with Felony

Convictions

Black people

Non-Black people

Population

People with Felony

Convictions

Source: 2010 Decennial Census;

virginiacourtdata.com

<!--*/

*/

/*-->*/

As a result of these dramatic disparities, Sterling Glen’s blanket ban is impermissible under both the federal FHA and Virginia state law.These laws not only prohibit housing providers from intentionally discriminating on the basis race, sex, disability, or other protected status, but also bar the application of any policy that has a disparate impact on one of these protected groups.

In place of blanket bans like Sterling Glen’s, the FHA requires that housing providers consider each housing applicant as an individual. By looking at not only the existence of a conviction, but the nature of their conviction or conduct, how long ago it occurred, and any evidence of rehabilitation, housing providers can make more fair decisions. Taking into account a prospective applicant’s post-conviction and post-release conduct, history as a tenant, and other similar factors provide important context into whether housing an applicant poses a risk to health or safety of the community.

The ACLU and ACLU of Virginia, in partnership with Relman, Dane & Colfax PLLC, a civil rights law firm with expertise in housing discrimination, are challenging the discriminatory blanket ban instituted at Sterling Glen on behalf of Housing Opportunities Made Equal (HOME), a Richmond-based nonprofit organization. HOME’s mission is to ensure equal access to housing for all by engaging in education and outreach, counseling individuals who face discrimination, undertaking investigations to uncover discrimination, and initiating enforcement actions.

Through this lawsuit, HOME aims to ensure every person has the opportunity to access safe, decent, affordable housing, regardless of their criminal history. The categorical exclusion of individuals with a criminal history has a discriminatory impact, is an ineffective means of assessing risk to residents and property, and violates both federal and state law. All housing providers should comply with the legal obligation to give all applicants the opportunity to access housing by considering them as individuals—not merely statistics.