As we approach the 2012 election, the fear that many Americans will be denied their right to vote is increasingly becoming a reality.

Laura W. Murphy is director of the ACLU Washington Legislative Office where she focuses on national security, criminal justice, human rights, privacy, civil rights and First Amendment issues. Previously, she founded Laura Murphy & Associates, L.L.C., where she guided and advised corporate and non-profit clients. Well known for her legislative advocacy on human rights and civil liberties, Laura has received numerous awards and honors for her significant contributions to legislation to advance key issues.

A growing number of states have enacted voter suppression laws that will require identification to vote, impose stricter voter registration requirements or prevent early voting or same-day voting — tactics that will push out many Americans from the electorate, particularly the elderly, people with disabilities, low-income voters, students and voters of color.

The generation of African-Americans before me would not have stood for this. They lived through "Bloody Sunday," the horrific march in Alabama where scores of nonviolent black protesters seeking the franchise were attacked by police. Because of the protesters' determination, they achieved political power and the protections of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

My mother, Madeline W. Murphy, born in 1922, was part of that generation. She and my father believed that every American should use voting power to participate in our democracy. They were so adamant that they would sometimes ask guests to leave our home if they learned they were not registered voters.

When my parents moved to the Cherry Hill neighborhood in Baltimore after World War II, the legacy of Jim Crow was apparent. Theirs was a large, segregated community with poorly repaired roads, broken street lights and other substandard government services. The elected officials in City Hall treated African-Americans as if they didn't exist.

While my father was practicing law, my mother was raising five children who were forced into overcrowded and underfunded public schools. In 1953, she recognized a need for another elementary school in our neighborhood, so she marched over to the City Council to make her case. But no council member took her demands seriously. Only 159 people were registered to vote in Cherry Hill, and she had no political leverage.

But that wasn't a roadblock for my mother. Over the next year, she started a voter registration drive and succeeded in registering 2,500 voters. From that day onward, Cherry Hill could no longer be ignored. As a result, four more elementary schools followed.

After decades of efforts by my parents and others in Baltimore, African-Americans were finally able to participate fully in elections. The political establishment became more accountable to the majority African-American community. My mother's leadership contributed to the election of Baltimore's first African-American mayor and first African-American member of Congress.

Mom ran for public office three times. Even though she never won, she was so notorious for her civil rights work that former Mayor Thomas D'Alesandro III nicknamed her "Geronimo."

When I reflect on this, I can't believe how close we are to losing what her generation fought so hard to achieve. Current Voter ID laws are no better than a poll tax; they shut out Americans who can't afford to pay for identification. Stricter voter registration laws stop registrants from going into rural and minority communities that are often ignored — just like the people of Cherry Hill before my mother arrived.

Elected officials who support these voter suppression measures, which have been introduced in more than 30 states and passed in 16, have a distorted understanding of democracy. In Maryland, the legislature has introduced three voter ID bills, two in the House and one in the Senate. These laws would deny registered voters access to the ballot if they do not have specifically required identification.

Even though most people think that everyone owns a photo ID, the reality is that millions of Americans do not, and a disproportionate number of these are low-income, racial and ethnic minorities and the elderly. Eighteen percent of Americans over the age of 65 do not have government-issued photo IDs. And many Americans cannot afford to pay for the required documents needed to secure a government-issued photo ID.

Voter ID laws are just one type of voter suppression tactic being proposed and enacted in states across the country. Others include laws that limit early voting periods, restrict third-party voter registration, eliminate same-day/Election Day voter registration and fail to restore voting rights for millions of Americans with past criminal convictions. Our elected officials should be seeking ways to encourage more Americans to vote, not inventing baseless reasons to deny voters the ability to cast their ballots.

My mother used to say, "You have to have fire in your belly and you've got to believe in your cause." Until she died in 2007, my mother's cause was motivating citizens to demand a more just and fair society through voting. There isn't a better time than Black History Month to recommit ourselves to what my mother and her generation spent their lives working to achieve.

(Originally published in the Baltimore Sun.)

This blog post is one of several personal testimonials written by ACLU staff members to commemorate Black History Month.

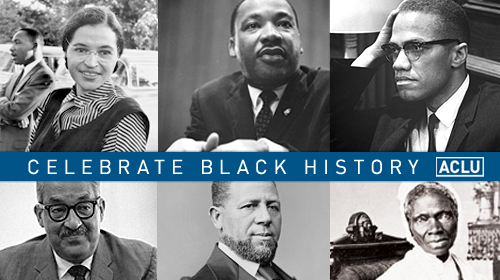

Do you know who’s pictured in our Celebrate Black History logo? Top row, from left to right: Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X. Bottom row, from left to right: Thurgood Marshall, Hiram Rhodes Revels and Sojourner Truth.

Learn more about civil rights: Sign up for breaking news alerts, follow us on Twitter, and like us on Facebook.