Remembering Martin Luther King Jr., the Organizer

Martin Luther King Jr. is rightly celebrated as a transformative political and moral leader who championed racial equality, but he is less often credited as a brilliant strategic and tactical organizer who led cutting edge campaigns to deliver the rights for which he is known. As an organizer, I am struck by the mastery of the organizing craft that infuses King’s writing, so on this holiday remembering his legacy, I’ll share several of King’s lessons that all activists can benefit from today.

King chose campaign targets strategically and partnered with local leadership

King’s campaigns were almost always local in scope and national in implication. Birmingham, the most segregated city in the South, was the target of a public accommodations campaign. King’s campaign in St. Augustine, Florida, a local Ku Klux Klan hub in a state whose governor supported ending segregation, tested whether the rule of law could triumph over racism. Selma, where voter registration was particularly hostile to Black citizens, was the locus of his voting rights campaign. Chicago’s residential segregation made it the ideal city for a northern open housing campaign.

King’s main political vehicle, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, had grassroots relationships in many Southern cities. Although King himself believed that, “No American is an outsider when he goes to the community to aid the cause of freedom and justice,” his entre into a city was usually by invitation from an ongoing local campaign. King would then collaborate with local leaders, essential for both building sustainable power and to protect King from ‘outside agitator’ allegations, and then follow up after the cameras had moved to ensure that reforms were implemented.

King developed innovative tactics in service of a cohesive strategy

King spent his career developing a strategy of non-violent resistance to persuade his primary target — moderate, movable white people — that civil rights were necessary. His campaigns used an evolving arsenal of tactics to support that strategy. In Clayborne Carson’s edited autobiography, King describes the 1962 Albany Movement campaign’s use of “direct action expressed through mass demonstrations; jail-ins; sit-ins; wade-ins, and kneel-ins; political action; boycotts and legal actions” to combat segregation in the Georgian city. King would turn the political pressure up and down depending on where and when he marched and used jailing as a tactic. This included a strategy around when to reject bail (remaining in jail for movement solidarity) and when to raise sufficient bail funds (so staff and volunteers could carry on critical work).

Some of King’s tactics evolved from his failures. When Albany ended without major victories due to what King called “vague” campaign goals, King designed the Birmingham campaign to focus on the desegregation of downtown stores.

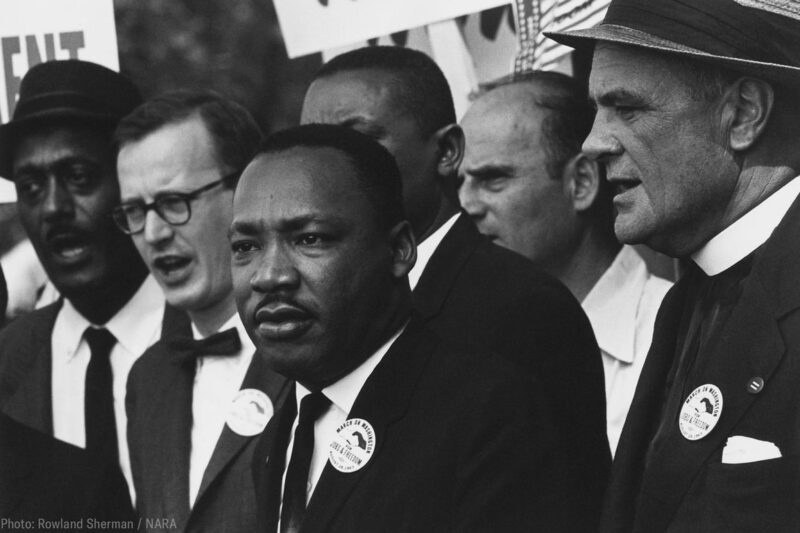

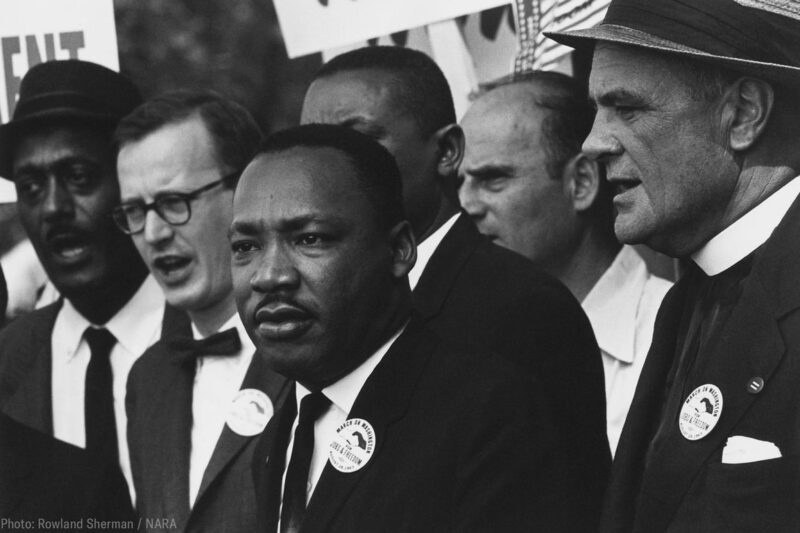

The famous 1963 March on Washington was a tactic with a particular goal in mind: Show white Americans what the civil rights movement looked like. For millions of white Americans tuning in on national television, the march’s well-dressed crowds and remarkable oratory ran completely counter to the fabrications they’d long been told about the Black civil rights movement, thus shifting their opinions on civil rights.

King even had a knack for employing celebrity support as a tactic. In a memo dictated from a Selma jail, King asked deputy Rev. Ralph Abernathy “to call Sammy Davis and ask him to do a Sunday benefit in Atlanta to raise money for the Alabama project. I find that all of these fellows respond better when I am in jail or in a crisis.”

King invested in others

An organizer invests in the leadership of other people, and King was committed to providing Black people with a “new sense of dignity and destiny” in his campaigns. In King’s campaigns, mass mobilization was an occasional tactic, but more essential was developing a cadre of core volunteers steeped and trained in the philosophy of non-violence and deeply committed to the movement. The 1963 Birmingham desegregation campaign, for example, launched with only 65 people — but each had pledged to serve up to five days in jail.

King was also willing to share the spotlight. At the height of the Albany Movement, King remained imprisoned in solidarity with other protesters rather than appear on “Meet the Press,” an opportunity he passed to a deputy. And despite deep misgivings over Kwame Ture's (then Stokely Carmichael) use of the term “black power” and refusal to commit to non-violence, King worked assiduously to keep their differences from derailing a joint march across Mississippi and publicly maintained a positive posture towards his younger partner.

King embraced politics as essential to making change

While politics is understandably distasteful to many activists, King’s political savvy was essential to his success. He conversed regularly with Vice President Richard Nixon during the Eisenhower administration and built a direct line to the Kennedy and Johnson White Houses. And while he was never afraid to criticize even his closest political allies, he also was always quick to issue a telegram of appreciation whenever a politician did the right thing.

King’s understanding of politics also informed his campaign tactics. Recognizing the movement’s lack of political power pre-voting rights, he focused on the economic pressure of boycotts or social pressure of direct action. While King famously wrote that direct action campaigns are never “well timed” in the view of the oppressor, he was actually quite savvy in his own timing. He delayed the start of the Birmingham campaign, for example, so that the campaign’s activism would not be detrimental to Public Safety Commissioner Bull Connor’s more moderate electoral opponent. Regarding political compromise, King recognized that victories, however small, are needed to “galvanize support and boost morale” in furtherance of a long-term movement. Of course, King was the ultimate disruptor, from the Montgomery Bus Boycott to the Poor People’s Campaign, and while he could work with politicians, his confrontational tactics never yielded to conventional politics.

These are just a few examples of the intentionality King brought to his organizing practice, which, married to his moral clarity, made him such a transformative visionary.

And while Martin Luther King Day is an important day to recognize the incredible achievements of one man, we should also the celebrate the iconic organizers who fought for civil rights alongside him, including Ella Baker, Bayard Rustin, Andrew Young, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, and so many others who nurtured dreams of civil rights into reality.

Their legacies live on today.